AP Syllabus focus:

‘Attempts to settle territorial slavery through national leadership and the courts could not permanently reduce sectional conflict.’

Limits of Compromise: Why Sectional Tensions Continued

National Leadership and the Failure to Resolve Territorial Slavery

Efforts by national leaders to quiet disputes over slavery repeatedly faltered because the fundamental disagreement—whether slavery could expand into western territories—remained unresolved. The Compromise of 1850, intended as an all-encompassing settlement, proved fragile almost immediately. While it temporarily delayed open conflict, it intensified mistrust between North and South.

The Unstable Politics of the Compromise of 1850

The compromise rested on several interlinked provisions that required ongoing cooperation between deeply divided sections.

California entered as a free state, shifting the balance of power in the Senate.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 inflamed northern opinion due to federal enforcement requirements.

The principle of popular sovereignty invited competition as proslavery and antislavery settlers vied for territorial control.

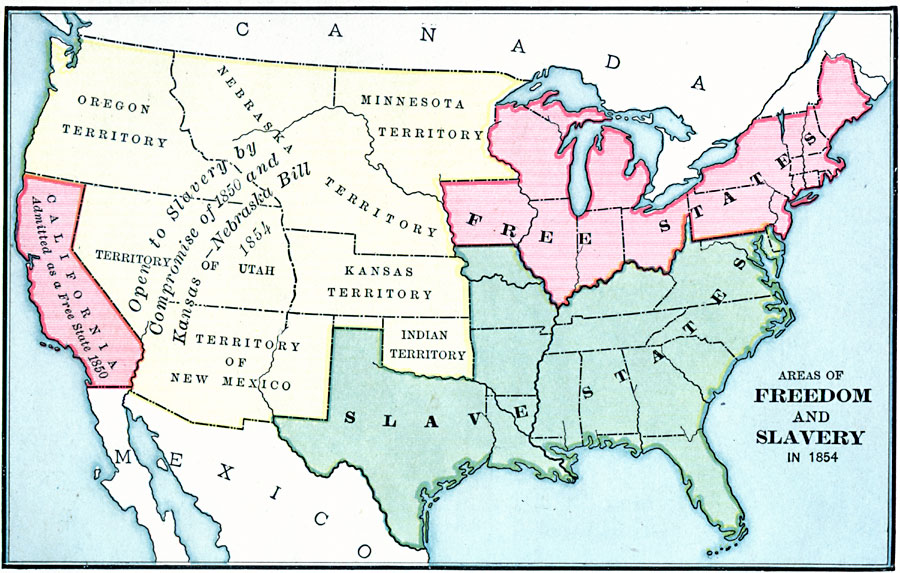

A color-coded map of free states, slave states, and territories in 1854 illustrates how the Compromise of 1850 and popular sovereignty destabilized earlier sectional balances. It shows California’s admission as a free state alongside western territories open to slavery, revealing how territorial governance reignited conflict. The map includes later 1854 context, but this additional detail clarifies why compromise repeatedly failed to settle sectional disputes. Source.

Popular Sovereignty: The principle that voters in a territory, rather than Congress, should decide whether to permit slavery.

Many Northerners viewed the Fugitive Slave Act as an aggressive imposition of slaveholding power.

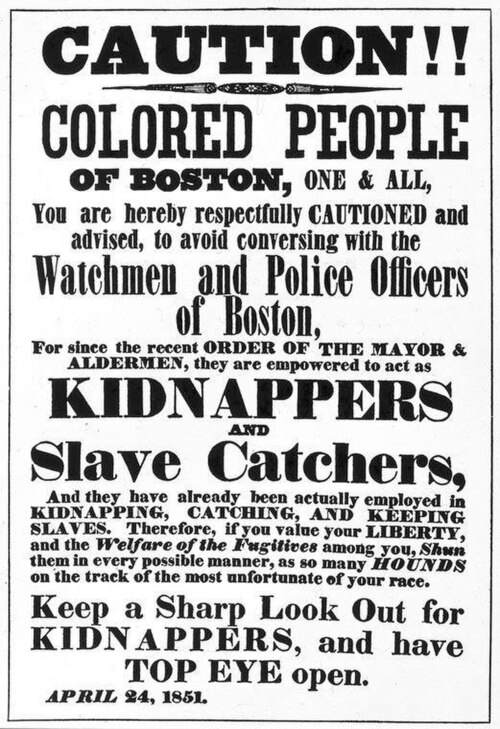

A Boston warning poster alerts Black residents that federal officers and slave catchers are empowered to seize fugitives under the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. It reflects northern communities’ fears that the law threatened both freedom and safety. The image focuses specifically on enforcement and resistance, illustrating why the act intensified sectional hostility. Source.

Many Southerners saw northern noncompliance as an attack on their constitutional rights. These mutual accusations made sustained compromise nearly impossible.

Judicial Attempts to Settle the Issue

Court interventions also failed to remove tensions. The judicial system increasingly appeared to serve sectional interests rather than national unity, eroding trust in federal institutions.

Southern politicians hoped courts would safeguard slavery’s expansion.

Many Northerners came to see federal rulings as extensions of proslavery influence.

Judicial outcomes deepened ideological divides rather than healing them.

Polarization of Public Opinion

The 1850s witnessed a pronounced hardening of northern and southern public attitudes. Newspaper editors, clergy, reformers, and political activists framed the debate in increasingly moral and existential terms.

Antislavery advocates denounced the extension of slavery as a national moral failing.

Proslavery defenders described any limit on slavery as a direct threat to southern society.

Political compromise was increasingly framed as surrender rather than negotiation.

Intensifying Sectional Identities

By mid-decade, both regions had developed strong sectional identities that made agreement harder.

Northerners emphasized free labor ideology, the belief that economic mobility depended on the absence of slave competition.

Southerners emphasized states’ rights, asserting that only decentralized authority could protect slavery.

Free Labor Ideology: The belief that a society based on free wage labor offered greater economic opportunity and moral superiority compared to slavery.

The narrowing ideological space prevented moderates from gaining traction. Each side feared that concessions would permanently weaken its political future.

Expansion of the United States and the Problem of New Territories

Territorial expansion repeatedly reopened the slavery question. Every newly acquired region—whether from the Mexican Cession or additional land purchases—required a decision about the legal status of slavery.

Settlers, politicians, and activists flooded new territories, eager to shape outcomes.

Local conflicts often mirrored national debates, creating flashpoints of violence and political manipulation.

The inability of Congress to craft universally accepted rules made every territory another battleground.

These disputes showed that compromise could delay but not solve competition for national dominance.

Breakdown of the Second Party System

The long-standing Democratic-Whig rivalry had previously helped channel sectional disputes into manageable political debates. By the early 1850s, however, the party system could no longer contain sectionalism.

Whigs splintered along sectional lines over slavery and enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act.

Democrats increasingly reflected southern priorities, creating distrust among northern voters.

New political movements emerged that centered directly on sectional concerns.

Moral Dimensions Undermining Pragmatic Compromise

As Americans debated slavery more publicly and passionately, moral condemnation replaced pragmatic bargaining. Religious revivals, abolitionist writings, and proslavery ideological defenses all framed the issue in moral absolutes.

Abolitionists portrayed compromise as betrayal of fundamental human rights.

Proslavery thinkers advanced arguments claiming slavery was a positive good, demanding recognition and protection rather than apologetic defense.

The widening moral gulf eliminated shared principles needed for lasting compromise.

As Americans debated slavery more publicly and passionately, moral condemnation replaced pragmatic bargaining.

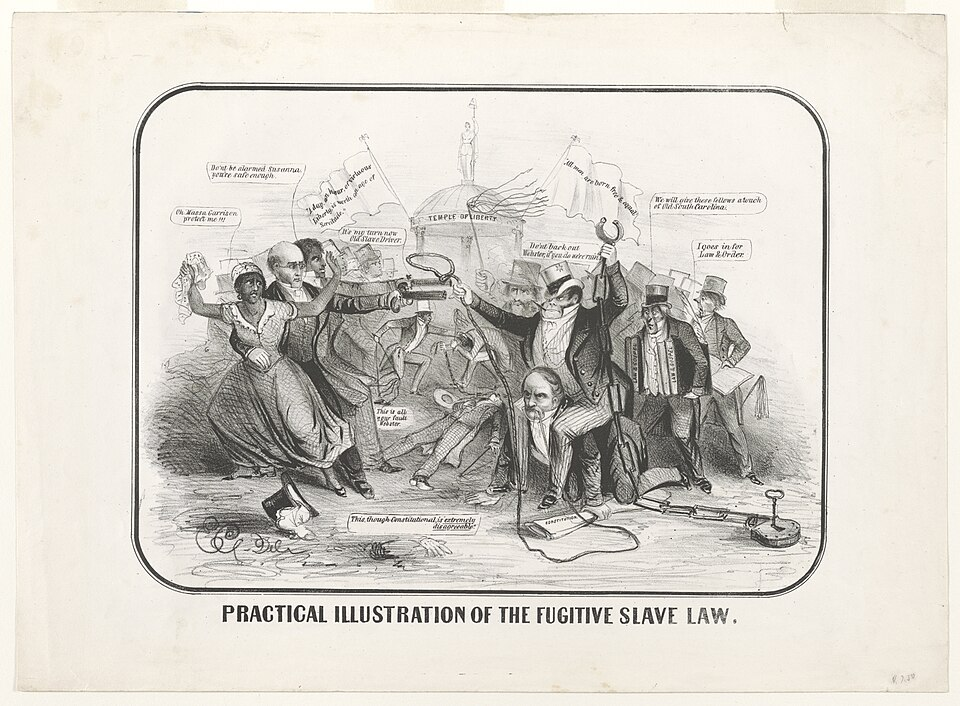

This political cartoon shows federal officers enforcing the Fugitive Slave Law as a Black man is seized, while abolitionists and politicians observe. It illustrates how many northerners viewed enforcement as both violent and unconstitutional, while southerners saw it as a protected federal obligation. Symbolic figures and labeled elements extend slightly beyond the syllabus, but they help clarify the deep moral conflict that made compromise increasingly untenable. Source.

Why Sectional Conflict Continued Despite Leadership and Court Efforts

Ultimately, every compromise failed because none addressed slavery’s centrality to American political, economic, and cultural life. Both sides saw the future of the nation at stake:

Southerners believed restrictions on slavery threatened their economic system and social order.

Northerners feared the “Slave Power” would dominate national institutions and undermine free labor.

Courts and national leaders lacked the authority or consensus to impose solutions.

Underlying ideological, economic, and political disagreements ensured that compromise could only postpone—not prevent—the deeper confrontation that would erupt into the Civil War.

FAQ

Moderates struggled because neither section trusted compromise advocates to protect their long-term interests. As political rhetoric hardened, moderation appeared indecisive or dangerous.

Public mobilisation also shifted the political landscape. Activists, clergy, editors, and local leaders framed the slavery question as a moral absolute, making compromise seem morally suspect.

Additionally, party structures that once elevated moderates were collapsing, reducing the institutional support they previously relied on.

Northern communities became deeply divided between those who insisted on legal obedience and those who viewed enforcement as incompatible with local values.

This produced:

• Expanded abolitionist networks and vigilance committees.

• Elections increasingly fought over personal liberty laws.

• New political figures emerging through resistance campaigns.

Municipal officials were frequently pressured to refuse cooperation, heightening local–national tensions that made future compromise more difficult.

Settlers brought sectional conflict directly into the territories, where their competing agendas made local governance unstable.

Many proslavery and antislavery migrants moved deliberately to influence territorial outcomes, ensuring immediate conflict over legislatures, courts, and land claims.

Their clashes—often encouraged by outside political interests—created real-world crises that national leaders struggled to manage, revealing the impracticality of purely legislative compromise.

The expansion of newspapers, rail links, and postal routes allowed sectional arguments to spread more quickly and uniformly.

Newspapers increasingly presented events through partisan or sectional lenses, reinforcing distinct northern and southern identities.

Improved communication also enabled coordinated political mobilisation, allowing both proslavery and antislavery groups to respond rapidly to perceived threats, leaving little space for compromise.

Southern leaders saw demographic and economic trends shifting national power towards the North, making future concessions riskier.

They feared that limiting slavery in western territories would permanently weaken southern political influence in Congress and the Electoral College.

The perception that northern states would not enforce agreements—especially regarding fugitive slaves—convinced many that compromise no longer offered security, but rather gradual marginalisation.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one reason why attempts to settle the issue of slavery in the territories during the early 1850s failed to reduce sectional tension.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark: Identifies a valid reason (e.g., the Fugitive Slave Act inflamed northern opinion).

2 marks: Provides a brief explanation showing why this reason increased sectional tension (e.g., northern resistance made southern leaders feel their rights were being ignored).

3 marks: Offers a clear, developed explanation showing how the reason directly prevented compromise or increased mistrust between North and South.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Evaluate the extent to which the Compromise of 1850 failed to provide a lasting solution to the problem of slavery’s expansion into the western territories. In your answer, consider both supporters’ hopes for the compromise and the reasons it ultimately intensified sectional conflict.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

4 marks:

Identifies at least two reasons why the Compromise of 1850 failed (e.g., controversial enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act; popular sovereignty created competition in the territories).

Provides basic explanation of how these reasons increased sectional conflict.

5 marks:

Gives developed explanations of multiple reasons, describing how each contributed to the failure of compromise.

Shows some understanding of why supporters initially believed the compromise might work.

6 marks:

Presents a well-argued evaluation of the extent of the compromise’s failure, with clear links between its provisions and the deepening sectional divide.

Demonstrates nuanced reasoning (e.g., recognising the compromise’s short-term stabilising effects but emphasising why structural disagreements made long-term peace impossible).

Uses specific, accurate historical examples to support points.