AP Syllabus focus:

‘After Lincoln’s victory, Americans engaged in contested debates about secession across the South and the nation.’

Tense political divisions after Lincoln’s 1860 election ignited fierce southern debates over whether secession was constitutional, necessary, or dangerously destabilizing for the slaveholding republic.

Secession as a Political and Constitutional Question

Southern debates over secession revolved around whether states possessed the constitutional authority to leave the Union. Many white southerners believed the Union was a voluntary compact among sovereign states.

Secession: The formal withdrawal of a state from the United States, claimed by some southern leaders as a constitutional right rooted in state sovereignty.

Although pro-secessionists dominated Deep South conventions, a significant minority believed secession was reckless or illegal. Political leaders drew on constitutional theory, founding-era precedent, and fears about federal overreach to justify their positions.

Compact Theory vs. Perpetual Union Claims

The compact theory (the belief that states created the Union and retained ultimate sovereignty) became a central justification for leaving the United States. Opponents countered that the Constitution established a perpetual union, citing the supremacy of federal law and the absence of any withdrawal clause.

Key tensions emerged around:

Whether Lincoln’s election constituted a legitimate political loss or an existential threat.

Whether states had the right to unilaterally dissolve their relationship with the federal government.

Whether disunion protected or endangered slavery.

Why Lincoln’s Victory Triggered Intensified Debate

Abraham Lincoln’s election without any southern electoral votes convinced many white southerners that the federal government was no longer responsive to their interests. The Republican Party’s free-soil platform, which opposed the expansion of slavery into the territories, deepened fears that slavery would face long-term restriction.

Southern Perceptions of Republican Hostility

Many slaveholders believed Lincoln’s administration would:

Appoint antislavery officials and judges.

Restrict slavery’s territorial growth, thereby weakening political power in Congress.

Encourage rising northern abolitionism.

However, Unionists argued that Lincoln had repeatedly pledged not to interfere with slavery where it already existed, urging patience and constitutional action rather than disunion.

Deep South vs. Upper South: Regional Variation in Debate

Secession debates unfolded differently across the South due to contrasting economic structures, demographic patterns, and political cultures.

Map showing the division of the United States at the start of the Civil War, with states that joined the Confederacy, border slave states, Union states, and western territories. The map highlights how slave states diverged in their responses to Lincoln’s election, illustrating the geographic pattern of secession debates. It includes additional territorial details not required by the syllabus but helpful for broader geographic context. Source.

Deep South: Faster Movement Toward Secession

States with:

Higher enslaved populations

Strong reliance on plantation agriculture

Deep cultural commitment to slavery

tended to secede first. These states viewed Lincoln’s victory as an immediate threat and believed secession would protect slavery, political autonomy, and regional honor.

Upper South: Caution and Conditional Unionism

The Upper South—with fewer enslaved people and more diversified economies—initially resisted immediate secession. Many leaders adopted conditional unionism, a stance advocating remaining in the Union unless the federal government used force against seceded states or moved directly against slavery.

Conditional Unionism: A political position in the Upper South that opposed immediate secession but supported leaving the Union if the federal government acted coercively or threatened slavery.

This approach created layered conversations about loyalty, economics, and security, revealing a broader range of southern political thought than often assumed.

Secession Conventions and Public Participation

Most southern states organized secession conventions, elected bodies tasked with debating and voting on withdrawal. These conventions featured heated arguments, public demonstrations, and competing resolutions.

Inside the Conventions

Delegates debated:

The legality of unilateral secession.

Whether cooperation with other southern states was necessary.

Economic consequences, including potential loss of northern trade.

National security considerations, such as federal forts in southern territory.

Pro-secessionists often relied on rhetoric about honor, self-defense, and the preservation of slavery, while unionists emphasized constitutional caution, economic risk, and the possibility of compromise within the Union.

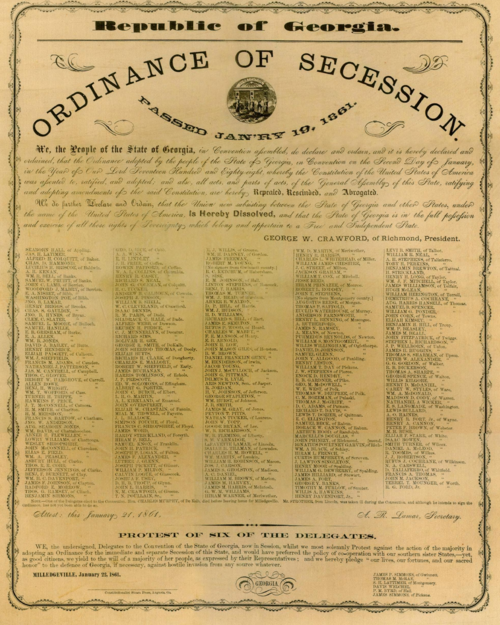

Once conventions voted for disunion, they drafted and signed ordinances of secession, formal legal documents declaring the state’s withdrawal from the Union.

Facsimile of Georgia’s 1861 Ordinance of Secession, listing delegates who voted to dissolve the state’s ties with the United States. The ornate heading and formal language illustrate how secessionists framed withdrawal as a solemn constitutional act. The document represents Georgia’s process but resembles similar ordinances across the Deep South. Source.

Public Opinion and Local Pressure

Despite limited electoral participation (many enslaved people and most women could not vote), intense local pressure shaped debates. Pro-secession newspapers, mass meetings, and vigilance committees influenced undecided delegates. In some areas, unionists faced harassment, marginalization, or threats.

Slavery as the Central Issue in Secession Debates

Although secession debates invoked constitutional theory and states’ rights, slavery remained the underlying issue. Southern leaders drew direct connections between:

Lincoln’s victory

Republican antislavery goals

The long-term survival of the slave system

Many speeches explicitly identified the defense of slavery as the primary motive for secession, while unionists argued slavery could still be safeguarded within the Union.

Economic and Social Stakes

Because slavery underpinned southern wealth, labor systems, and racial hierarchy, any political threat to the institution sparked anxiety about social upheaval. Secession thus appeared to many as a necessary action to protect the South’s economic and cultural order.

National Reactions to Southern Debates

While southern leaders deliberated, northern newspapers, politicians, and citizens watched closely. Some urged compromise measures—such as the Crittenden Compromise—to placate slave states. Others believed any concession would reward disunionist threats.

Cross-Regional Tension

The existence of open debates over secession intensified national polarization by:

Highlighting deep ideological divisions.

Undermining remaining trust between regions.

Prompting urgent discussions about federal authority and the future of the Union.

In some states, voters or convention delegates split sharply along regional lines, with upcountry or mountain counties often resisting secession.

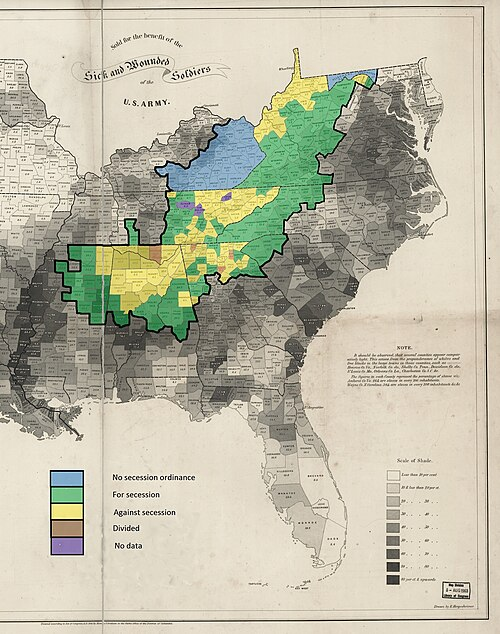

County-by-county map of secession voting patterns in the Appalachian regions, showing where support for or opposition to secession was strongest. The black-outlined Appalachian region and the color gradient for enslaved population percentages provide context for why these counties often resisted secession. These demographic layers extend beyond syllabus requirements but help illuminate regional political divisions. Source.

National uncertainty grew as individual southern states reached different decisions at different times, signaling that the crisis was spreading rather than resolving.

The Secession Decision and Its Broader Significance

By early 1861, the Deep South states had voted to secede, while the Upper South waited. The debates revealed:

The fragility of national political institutions

The centrality of slavery in American politics

The competing visions of constitutional meaning

Secession debates in the slave states thus became a crucial turning point, escalating from political disagreement into the national crisis that precipitated the Civil War.

FAQ

Southern newspapers played an essential role in framing secession as either a necessary defence of slavery and southern rights or a reckless move endangering stability.

Editors often used emotionally charged rhetoric, portraying Lincoln as a radical threat or, alternatively, urging caution and constitutional patience.

Many smaller communities relied heavily on a single local paper, meaning its stance could significantly influence delegates and voters during secession debates.

Honour culture encouraged southern elites to interpret political conflict through the lens of reputation, masculinity, and regional dignity.

Pro-secession politicians argued that staying in the Union after Lincoln’s victory would signal weakness and acceptance of northern hostility.

This mindset sometimes made compromise appear dishonourable, increasing pressure on leaders to support immediate withdrawal even when practical risks were high.

Many Upper South slaveholders held fewer enslaved individuals and operated in more diversified economies, reducing fears of sudden economic collapse under a Republican administration.

They tended to believe that slavery remained secure under the Constitution and expected Lincoln to abide by his pledge not to interfere where slavery already existed.

Some also feared that secession would provoke destructive conflict likely to reach their farms and towns.

Secession conventions were specially elected bodies with the sole purpose of determining whether a state should leave the Union.

Differences included:

Delegates were often chosen in highly politicised elections centred on secession alone.

Conventions could draft binding ordinances independent of normal legislative approval.

Debates were more ideologically charged, with intense scrutiny from local communities, militias, and newspapers.

These features made conventions a unique political arena during the crisis.

Unionists highlighted the economic risks of breaking with the North, emphasising potential losses in trade, transportation links, and access to manufactured goods.

They also warned that federal military action against seceded states could spark widespread violence and financial instability.

Some argued that secession offered no realistic long-term strategy, as the new Confederacy would struggle diplomatically and militarily against the established United States.

Practice Questions

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Explain how debates over secession in the slave states reflected broader political and social divisions within the South in the period 1860–1861.

Mark scheme:

Up to 2 marks for explaining political divisions (e.g., compact theory vs. belief in a perpetual union; disagreements within secession conventions; constitutional interpretations).

Up to 2 marks for explaining social or economic divisions (e.g., areas with fewer enslaved people showing more Unionist sentiment; differing regional economic interests; influence of slavery on political alignment).

Up to 1 mark for integrating specific examples (e.g., Deep South vs. Upper South divergence; county-level resistance in upcountry regions).

Up to 1 mark for demonstrating clear analytical linkage between the debates and broader sectional tensions (e.g., how the debates foreshadowed the fragmentation of national political institutions).

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify one reason why some white southerners opposed immediate secession following Lincoln’s election in 1860. Explain why this reason contributed to their opposition.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying a valid reason (e.g., belief that secession was unconstitutional, economic fears, preference for compromise, trust in Lincoln’s non-interference pledges).

1 mark for explaining why this reason contributed to opposition (e.g., constitutional caution suggested remaining in the Union; economic ties to the North made secession risky).

1 additional mark for a further specific detail or clear contextualisation (e.g., Upper South conditional unionism; reliance on diversified economies).