AP Syllabus focus:

‘Most slave states voted to secede from the Union after 1860, precipitating the Civil War.’

The secession crisis of 1860–1961 unfolded from escalating sectional tensions, contested political authority, and Southern fears about slavery’s future, ultimately triggering armed conflict between the Union and the Confederacy.

The Secession Crisis After Lincoln’s Election

Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860 was a critical turning point in American politics. Although he pledged not to interfere with slavery where it already existed, his Republican free-soil stance convinced many white Southerners that the federal government was now controlled by a party fundamentally opposed to their economic and social order. Lincoln’s victory without carrying a single Southern state intensified Southern beliefs that they had lost national influence and created the political conditions that encouraged secession.

Southern Fears and the Perceived Threat to Slavery

Many white Southerners believed the survival of racial slavery—the foundation of their labor system and social hierarchy—depended on leaving the Union. Slavery had increasingly come under moral and political attack in the North, and Southerners argued that even containing slavery’s expansion would eventually destabilize the institution where it already existed.

To justify secession, Southern leaders framed the crisis as one of states’ rights, asserting that states retained sovereignty and could withdraw from the Union when the federal government acted against their interests.

States’ Rights: The political doctrine that individual states possess autonomous authority and may resist or nullify federal actions perceived as unconstitutional.

Many white Southerners accepted this argument because it aligned with decades of sectional disputes and reinforced their view that Northern political power posed an existential threat.

The First Wave of Secession

Following Lincoln’s election, South Carolina acted first, seceding on December 20, 1860. Its leaders claimed that the compact binding the states together had been broken. Between January and February 1861, six additional Deep South states—Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas—followed.

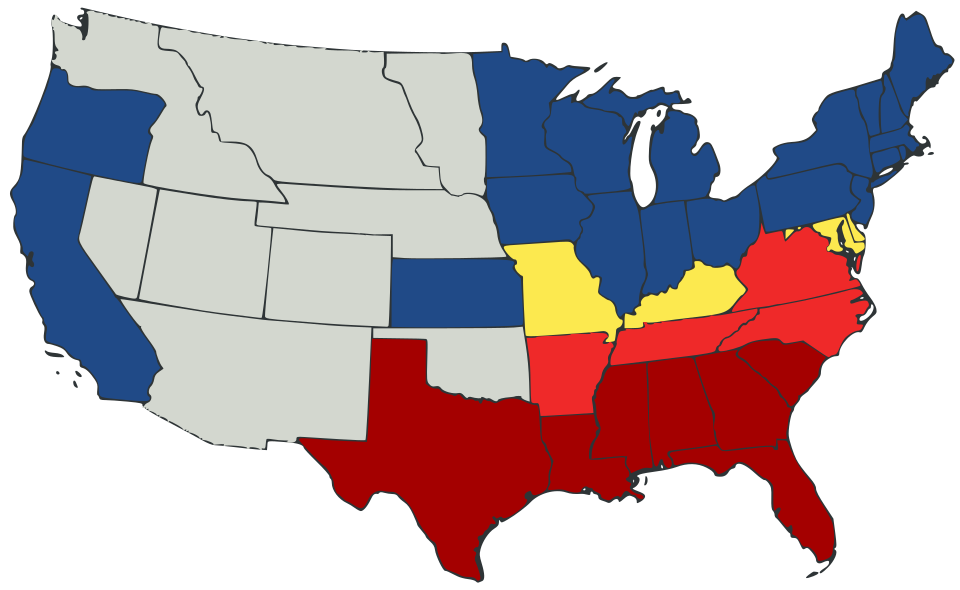

Map showing seceding and non-seceding states in 1861, illustrating the geographic pattern of Deep South and Upper South departures from the Union. The color-coding highlights how most slave states formed the Confederacy. The map also includes Union territories, which is slightly broader context than the syllabus but consistent with AP-level understanding. Source.

Formation of the Confederate States of America

The seven seceded states created the Confederate States of America, established a provisional government in Montgomery, Alabama, and elected Jefferson Davis as president. They drafted a constitution that closely resembled the U.S. Constitution but explicitly protected slavery and limited federal authority.

The Confederacy’s rapid formation demonstrated how deeply pro-slavery ideology and sectional nationalism had taken root in the Deep South.

The Upper South’s Reluctant Decision

While the Deep South seceded quickly, the Upper South—including states such as Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansas—initially resisted immediate withdrawal. Many residents of these states had stronger economic ties to the North and fewer enslaved people. However, as tensions escalated, loyalty was fiercely debated across households, legislatures, and communities.

The Fort Sumter Crisis and Expanded Secession

The national crisis intensified when Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumter in April 1861 after Lincoln attempted to resupply the fort.

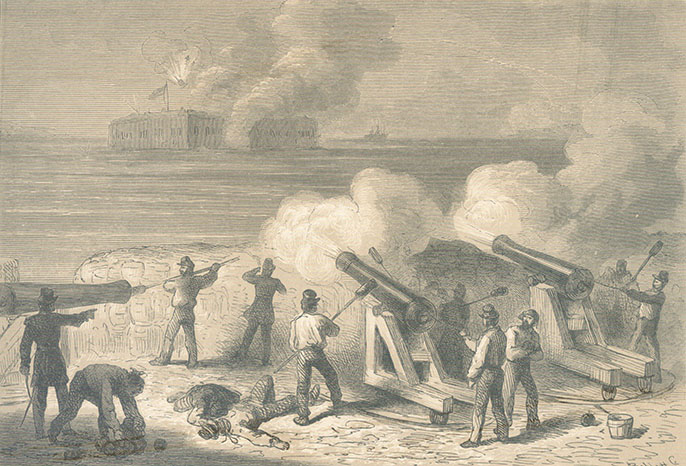

Artist’s rendering of Confederate batteries firing on Fort Sumter in April 1861, marking the opening of the Civil War. The foreground shows artillery crews while Fort Sumter appears in the distance under smoke. Additional context such as nearby batteries is present but still supports understanding of the event’s scale. Source.

Lincoln’s subsequent call for 75,000 volunteers to suppress the rebellion convinced the Upper South that the federal government sought coercive military action against fellow Southern states.

This moment transformed reluctant states into full participants in the Confederate cause. Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina seceded soon after, completing the Confederacy’s core membership and ensuring that the coming conflict would be a full-scale civil war rather than a limited regional uprising.

The Debate Over Union and Disunion

Secession was not universally supported in the South. Large pockets of Unionist sentiment persisted, especially in regions with fewer enslaved laborers—such as eastern Tennessee, western Virginia, and northern Alabama. Many residents of these areas opposed secession because they feared war, distrusted planter elites, or believed the Union offered better long-term stability.

Northern attitudes also varied. While many Northerners were determined to preserve the Union, initial war aims focused primarily on restoring the nation rather than abolishing slavery.

Unionism: The political belief that the United States was an indissoluble nation and that states could not lawfully secede from the federal Union.

Unionist arguments emphasized constitutional permanence and national identity, countering Southern claims of state sovereignty.

Secession as the Immediate Cause of the Civil War

The decision of most slave states to secede after 1860 directly precipitated the Civil War by challenging the legitimacy of the federal government and creating a rival nation based on the preservation of slavery. Secession forced the issue of whether the United States was a voluntary compact of states or a permanent national entity.

By rejecting the outcome of a constitutional election and seizing federal property, the Confederacy compelled Lincoln to respond, setting the stage for armed confrontation.

Photograph of the interior of Fort Sumter immediately after the April 1861 bombardment, showing collapsed structures and heavy destruction. The visual underscores how the opening clash moved the secession crisis into open warfare. Additional context about later modifications appears on the hosting page but is not shown in the photograph. Source.

The inability of the Union and the Confederacy to compromise on the fundamental issues of sovereignty and slavery made conflict unavoidable, marking secession as the pivotal step toward the outbreak of war in 1861.

FAQ

Southern secession conventions served as formal bodies empowered to debate and vote on withdrawal from the Union. Delegates were often selected by local elites, ensuring strong pro-secession representation.

These conventions produced official declarations that framed secession around constitutional violations, the protection of slavery, and the defence of Southern rights.

Their published documents also helped build public support by presenting secession as a lawful and necessary act rather than rebellion.

Economic diversity shaped levels of support for secession across the South.

• Regions with high concentrations of enslaved labour, such as the plantation belts, strongly supported immediate secession.

• Areas with mixed agriculture, limited slavery, or smaller farms—particularly in the Upper South and mountainous regions—showed greater Unionist sentiment.

These economic variations contributed to internal divisions and made the South far from politically uniform.

Southerners often viewed containment of slavery as the first step toward its elimination.

They believed that restricting the institution’s expansion would:

• Reduce political representation in Congress over time

• Limit access to new slaveholding land

• Strengthen Northern antislavery influence in national politics

This convinced many Southerners that the Union’s long-term trajectory threatened their entire social order.

Yes. Moderates in several Southern states sought compromise through conferences, negotiations, or conditional Unionism.

These efforts included:

• Proposals to wait for Lincoln’s inaugural address

• Attempts to secure new constitutional protections for slavery

• Statewide referendums or debates urging caution

However, rapid secession by Deep South states created momentum that undermined such moderate voices.

The Upper South’s decision hinged on differing economic structures, fewer enslaved people, and stronger ties to national institutions.

Initially, many residents believed secession was too extreme and hoped for a negotiated settlement.

After Fort Sumter, the situation changed: Lincoln’s mobilisation order was perceived as forcing states to choose between fighting against fellow Southerners or leaving the Union.

This shift transformed reluctant states into committed participants in the Confederacy.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one reason why the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860 contributed to the secession of Southern states.

Mark scheme:

Award up to 3 marks:

• 1 mark for identifying a valid reason (e.g., Southern fears over the Republican Party’s stance on slavery).

• 1 mark for explaining how Lincoln’s free-soil platform was perceived as a threat to the expansion or stability of slavery.

• 1 mark for linking this perception to Southern political calculations that secession was necessary to protect their interests.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Assess the extent to which the firing on Fort Sumter transformed the secession crisis into a full-scale civil war.

Mark scheme:

Award up to 6 marks:

• 1 mark for a clear statement of argument regarding the significance of Fort Sumter.

• 1 mark for describing the immediate impact of the bombardment (e.g., the collapse of remaining hopes for compromise).

• 1 mark for explaining Lincoln’s call for 75,000 volunteers after the attack.

• 1 mark for detailing how this mobilisational response influenced the Upper South’s decision to secede.

• 1 mark for making a connection between these developments and the shift from political tension to military conflict.

• 1 mark for overall coherence and use of accurate, relevant evidence from the period.