AP Syllabus focus:

‘Corporations needed managers and male and female clerical workers; expanded educational access helped create a distinctive middle class.’

The expansion of white-collar work and access to formal education in the late nineteenth century reshaped American society, creating a distinctive middle class whose cultural values and occupations reflected the broader transformations of the industrial economy.

The Rise of White-Collar Occupations

The emergence of large corporations after the Civil War fundamentally altered the structure of the American workforce. As businesses expanded in size and complexity, they required new layers of administrative labor to coordinate production, track finances, market goods, and manage a national customer base. This demand produced rapidly growing numbers of white-collar workers, a group that differed from both wage-earning laborers and wealthy industrialists.

Corporate Growth and Administrative Needs

Industrialization multiplied the scale at which companies operated, necessitating specialized tasks that could not be handled by owners alone. These tasks included:

Accounting and bookkeeping, required to track increasingly complex financial flows.

Clerical work, including correspondence, filing, payroll, and document management.

Middle management, a new professional layer responsible for supervising workers and enforcing company policies across geographically dispersed facilities.

Sales and marketing roles, which became central as companies sought national markets.

White-collar work: Non-manual, salaried employment in administrative, managerial, or professional positions associated with offices rather than industrial production.

The growth of these occupations signaled a shift from a predominantly manual labor force to one that included significant numbers of workers performing tasks tied to information, coordination, and communication. This shift reshaped social hierarchies and aspirations, offering alternatives to factory and agricultural labor.

Women and the Expanding Clerical Workforce

Technological innovations such as the typewriter, improved filing systems, and business-standardized communication methods opened new opportunities for women. Corporations increasingly relied on female clerical workers, whose labor was considered efficient, orderly, and—according to biased assumptions of the era—more suited to repetitive administrative tasks.

Changing Gender Roles in Offices

The feminization of clerical work marked a major social transformation. Women entered public workplaces in numbers not previously seen, particularly in urban centers.

Lillian J.B. Thomas, a stenographer in Lexington, Kentucky, represents the new cohort of educated women entering clerical occupations. Her work relied on literacy, shorthand, and typewriting skills increasingly taught in schools and commercial programs. The image also suggests limited but meaningful opportunities for African Americans within the emerging urban middle class. Source.

Their roles included:

Typing business correspondence

Managing office records

Operating communications technologies such as telephones

Performing customer-facing clerical duties

Although wages for women remained significantly lower than those for men, clerical work nonetheless offered a path to economic self-sufficiency. It also enabled many women to pursue education or urban lifestyles that would influence later social reform movements.

A sentence placed here ensures proper separation before any additional block content.

Clerical labor: Office-based work involving recordkeeping, communication management, and administrative support within a corporate or institutional setting.

Education and the Making of a Middle Class

The rise of white-collar work was closely tied to expanded educational access. As businesses became more bureaucratic, they preferred workers who possessed literacy, numeracy, and formal training. This preference encouraged growth in:

Public high schools, which spread rapidly across the country

Normal schools (teacher-training institutions)

Business colleges, which taught stenography, accounting, and typing

Universities, especially land-grant schools created by the Morrill Acts

Education as a Pathway to Mobility

Increased educational opportunities did more than prepare workers for office jobs; they also contributed to a shared set of cultural norms.

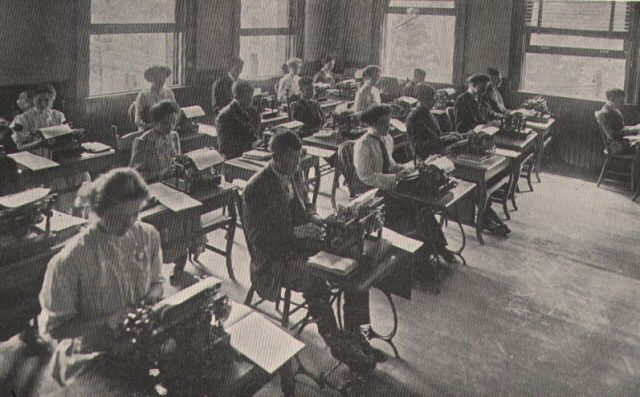

Students at Toledo Central High School typewriting class in 1909 practice clerical skills increasingly required by expanding corporations. Public high schools incorporated business-oriented training to prepare students for white-collar roles. Although slightly later than the AP period, the image visually reflects trends in late-nineteenth-century educational and occupational change. Source.

Parents increasingly viewed education as an investment in their children's socioeconomic mobility. As a result, schooling became a key marker distinguishing the emerging middle class from both industrial laborers and rural farmers.

A Distinctive Middle-Class Culture

The expansion of white-collar work and education produced a new social stratum characterized by unique behaviors, aspirations, and cultural patterns. Members of this middle class typically sought stable incomes, home ownership, and participation in civic life. They often embraced ideals of self-improvement, respectability, and professional advancement, aligning closely with prevailing notions of American progress.

Lifestyle and Identity

Several cultural developments accompanied the rise of the middle class:

Growth in consumer goods marketed specifically to office workers and professionals

Increased participation in organized leisure, clubs, and community associations

Adoption of gendered expectations, with male workers pursuing managerial authority and women often balancing clerical employment with domestic responsibilities

Expansion of print culture—newspapers, magazines, and self-help literature—that reinforced middle-class norms

These trends reflected how white-collar employment not only changed work but also transformed everyday life, shaping patterns of consumption, social mobility, and identity.

Broader Economic and Social Implications

The emergence of a professional and clerical labor force helped stabilize industrial capitalism by creating workers who were invested in the system’s success. White-collar employees often perceived themselves as distinct from manual laborers, reducing the likelihood of cross-class labor alliances. At the same time, their roles strengthened corporate hierarchies and centralized decision-making within expanding firms.

The creation of a new middle class, therefore, represented more than an occupational shift—it reflected deeper economic and cultural changes that defined the Gilded Age.

FAQ

New technologies such as the typewriter, adding machine, carbon paper duplicating systems, and improved filing cabinets dramatically increased office efficiency.

These tools standardised clerical processes, allowing corporations to expand administrative departments and employ more clerks, typists, and bookkeepers.

They also encouraged specialisation within offices, creating distinct roles such as stenographer, typist, or ledger clerk, each requiring training and contributing to the rise of a structured white-collar workforce.

The largest expansions came from railroads, insurance companies, banks, and manufacturing corporations.

These enterprises operated across vast geographic areas and required extensive administrative systems to manage logistics, payroll, accounting, and customer communication.

Their bureaucratic structures became models for other industries and helped set national expectations for white-collar office work.

Middle-class office culture emphasised punctuality, personal presentation, handwriting or typing accuracy, and adherence to hierarchical organisational structures.

Workers cultivated identities centred on respectability, routine, and professional behaviour, which aligned with broader middle-class social values.

This contrasted with industrial settings, where physical skill, endurance, and collective shop-floor culture were more influential.

Yes, but opportunities were uneven.

Many immigrants—especially those with literacy in English or previous clerical experience—could enter low-level office positions, particularly in urban areas.

However, barriers such as language, discrimination, and informal hiring networks often limited access to managerial roles, meaning upward mobility was possible but not uniform.

Employers often assumed women would accept lower wages and perform repetitive clerical tasks reliably, making them economically attractive hires.

Cultural beliefs about women’s supposed patience, neatness, and moral propriety also shaped recruitment.

As more women entered offices, clerical roles gained a gendered reputation, while managerial roles remained coded as male, reinforcing occupational hierarchies even within the expanding white-collar sector.

Practice Questions

Explain one way in which expanding educational opportunities contributed to the rise of the white-collar middle class in the late nineteenth century. (1–3 marks)

1. Explain one way in which expanding educational opportunities contributed to the rise of the white-collar middle class. (1–3 marks)

• 1 mark: Identifies a relevant way education contributed (e.g., provided literacy or technical skills needed for office work).

• 2 marks: Gives a developed explanation linking education to access to white-collar employment (e.g., growth of high schools and business colleges created a trained pool of clerical workers).

• 3 marks: Provides specific detail or clear contextualisation (e.g., the spread of public high schools and commercial training enabled both men and women to pursue clerical and managerial roles, supporting the emergence of a new middle class).

Assess the extent to which the growth of clerical and managerial work transformed gender roles and social class structure in the United States between 1865 and 1898. (4–6 marks)

2. Assess the extent to which clerical and managerial work transformed gender roles and social class structure, 1865–1898. (4–6 marks)

• 4 marks: Describes relevant changes to gender roles or class structure (e.g., increased participation of women in office work; rise of salaried middle-class occupations).

• 5 marks: Provides analysis showing how these changes altered social expectations, economic mobility, or workplace hierarchies (e.g., feminisation of clerical work, new norms of respectability and professionalism).

• 6 marks: Presents a well-reasoned judgement on the extent of change, supported by specific evidence (e.g., although clerical work offered opportunities, women remained lower paid; middle-class identity solidified through education and office culture; continuity remained in male dominance of senior roles).