AP Syllabus focus:

‘Many women, including Jane Addams, worked in settlement houses to help immigrants adapt to U.S. language, customs, and urban life.’

Settlement houses emerged as crucial urban institutions where reformers, most prominently Jane Addams, assisted immigrants in navigating language barriers, cultural transitions, and economic hardships within rapidly changing American cities.

The Rise of Settlement Houses in the Gilded Age

Settlement houses developed in response to the rapid influx of immigrants into industrial cities during the late nineteenth century. Reformers believed poverty and assimilation challenges stemmed partly from environmental conditions. By placing educated, middle-class residents directly in poor neighborhoods, settlement houses aimed to uplift communities through education, cultural exchange, and social services.

Key Goals of the Settlement Movement

Reformers pursued several interrelated objectives designed to assist newcomers facing the pressures of urbanization:

Promoting assimilation through English-language instruction and civic education.

Providing social support, including childcare, employment services, and recreation.

Improving neighborhood conditions through advocacy, research, and collaboration with municipal authorities.

Encouraging cross-class interaction to reduce social divisions and foster mutual understanding.

These goals shaped the ethos of the most influential institution of the movement: Hull House.

Jane Addams and the Founding of Hull House

Jane Addams became the central figure of the settlement house movement after co-founding Hull House in Chicago in 1889.

Jane Addams, photographed in the early 20th century, was a leading Progressive Era reformer and the most prominent figure in the settlement house movement. As cofounder of Hull House in Chicago, she worked directly with immigrant families to address poverty, education, and labor conditions. Her activism linked neighborhood work with broader campaigns for social and political reform. Source.

Addams believed that genuine reform required living among those one sought to help, grounding social activism in firsthand knowledge of immigrant life. Hull House quickly expanded from a single residence to a sprawling complex that addressed multiple immigrant needs.

The front steps of Hull House show the preserved exterior of the original settlement building. Immigrants accessed classes, childcare, recreation, and social services through this entrance. Its location in a working-class neighborhood reflects the settlement movement’s commitment to living among the communities it served. Source.

Addams’s Philosophy of Social Reform

Addams’s approach integrated moral philosophy, pragmatism, and democratic ideals. She viewed immigrants not as passive recipients of aid but as partners whose cultural contributions enriched American society.

Assimilation: The process by which immigrants adopt aspects of a host society’s language, customs, and institutions—often while reshaping them through their own cultural practices.

Her philosophy emphasized cooperation over coercion and respected the dignity and agency of immigrant families, which distinguished settlement houses from more paternalistic charities.

A significant feature of Addams’s leadership was her insistence that settlement workers gather data on social conditions. This practice allowed reformers to shape public policy with empirical grounding.

Programs and Services Supporting Immigrant Adjustment

Hull House and similar institutions developed wide-ranging programs designed to meet both practical needs and cultural aspirations.

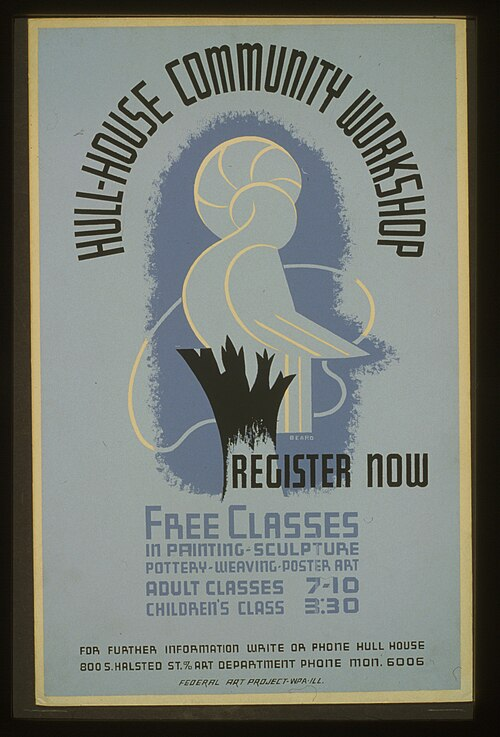

A 1938 WPA poster advertises arts classes at the Hull-House community workshop, including sculpture and painting. The imagery symbolizes personal growth and cultural creativity fostered by settlement programs. The WPA design reflects New Deal–era arts support, an additional historical layer that remains consistent with the broader narrative of community uplift. Source.

Educational Initiatives

Settlement houses offered:

English-language classes, essential for employment and civic participation.

Citizenship courses that prepared newcomers for naturalization exams and involvement in public life.

Lectures and reading groups that invited immigrants to engage in broader intellectual and cultural discussions.

These educational programs aimed not only at skill acquisition but also at fostering confidence and community belonging.

Social and Recreational Programs

Because urban immigrants often lived in overcrowded, stressful environments, settlement houses supplied recreational outlets that provided relief and encouraged interpersonal connections.

Children’s clubs and playgrounds supported healthy development.

Theater groups, music schools, and art classes enabled creative expression and cultural exchange.

Community festivals celebrated ethnic traditions, reinforcing pride while facilitating engagement with American society.

These efforts recognized that adaptation to a new culture involved emotional and social dimensions, not just economic survival.

Employment and Economic Assistance

Settlement houses helped newcomers navigate labor markets shaped by industrial capitalism’s instability. Staff provided:

Job-placement assistance connecting workers to safer or more reliable employment.

Training programs in domestic labor, clerical work, and crafts.

Cooperative workshops where immigrants—especially women—could earn wages under fairer conditions than factory work offered.

By helping immigrants assert greater control over their economic lives, settlement houses mitigated some of the exploitation common in urban labor markets.

How Settlement Houses Shaped Urban Reform

Hull House set a national standard for progressive reform by linking local service to broader advocacy. Addams and her colleagues pushed for policies that would improve the lives of immigrant communities beyond the walls of the settlement.

Research and Legislative Impact

Settlement workers conducted neighborhood surveys that documented:

Child labor practices

Sanitation problems

Housing conditions

Industrial accidents

These findings fueled campaigns for protective legislation such as child labor laws, improved factory safety, and urban sanitation reforms.

Women’s Expanding Public Role

The settlement movement also created new opportunities for middle-class women to participate in public life at a time when formal political roles remained restricted. Women like Addams became:

Policy advocates influencing local and state governments.

Community organizers shaping responses to poverty and immigration.

Public intellectuals contributing to debates on democracy, social ethics, and American identity.

Their work demonstrated that civic engagement could extend beyond voting, laying groundwork for future reforms.

Cultural Exchange and the Limits of Assimilation Efforts

While settlement houses promoted Americanization, they also celebrated immigrant cultural identity. Hull House’s programs frequently highlighted ethnic music, festivals, and artistic traditions, encouraging a more pluralistic notion of American society.

However, the movement was not without limitations. Some reformers assumed that American middle-class norms were superior, and assimilation pressures could unintentionally marginalize cultural practices. Despite these tensions, many immigrants valued the support, safety, and empowerment settlement houses offered, and the institutions became vital spaces of adjustment and community formation.

FAQ

Hull House was located in a densely populated, mixed-ethnicity neighbourhood that included Italian, Greek, Russian Jewish, Irish, and later Mexican immigrants.

This diversity encouraged the development of flexible, culturally responsive programmes.

Language classes were tiered to accommodate different levels.

Cultural festivals were designed to showcase multiple traditions rather than a single ethnic narrative.

Social workers often adapted services to religious calendars and gender norms within specific communities.

These conditions made Hull House a laboratory for cross-cultural engagement.

Hull House pioneered the use of empirical neighbourhood studies, mapping living conditions, wages, and child labour patterns.

Their work contributed to early models of casework and community studies by:

Standardising interview practices.

Demonstrating the value of long-term, immersive observation.

Linking local data to legislative advocacy, such as factory inspection laws.

Many Hull House residents later shaped university-based social work education, embedding research-led approaches into the profession.

Children were considered central to long-term immigrant adjustment, so Hull House invested heavily in youth services.

Support included:

After-school clubs to keep children safe during parents’ long work hours.

Summer camps that offered recreation unavailable in crowded urban areas.

Classes in music, drama, and crafts that promoted confidence and cultural expression.

These activities softened the impact of urban poverty while helping young people navigate both home and American school cultures.

Immigrant women not only used services but also contributed to programme development.

Many brought expertise in cooking, sewing, childcare, or folk traditions, which influenced workshops and community events. Some worked as interpreters or cultural mediators, aiding communication between residents and social workers.

Hull House also provided leadership opportunities, allowing immigrant women to organise clubs, teach skills, or speak publicly on neighbourhood issues—experiences rarely available in their workplaces or homes.

Some critics argued that settlement houses, despite good intentions, encouraged cultural conformity by promoting Americanisation.

Others felt the movement relied too heavily on middle-class assumptions, such as idealised domestic roles or expectations of punctuality and discipline.

A practical criticism concerned scale: settlement houses could not reach most urban immigrants, and their resources were stretched thin. Additionally, a few immigrant leaders believed political empowerment, not social uplift, was the more effective long-term solution to poverty and exploitation.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which Jane Addams’s Hull House helped immigrants adjust to life in the United States during the late nineteenth century.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark:

Identifies a valid action or service provided by Hull House (e.g., English classes, childcare, job assistance).

2 marks:

Provides a clear explanation of how the identified action supported immigrant adjustment (e.g., how language classes improved employment opportunities or civic participation).

3 marks:

Offers a developed explanation showing a clear link between Hull House activities and broader challenges faced by immigrants in urban settings (e.g., connecting services to overcrowding, labour exploitation, or cultural transition).

(4–6 marks)

Analyse how the settlement house movement reflected broader Progressive Era beliefs about poverty, immigration, and social reform. In your answer, refer specifically to the work carried out at Hull House.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

4 marks:

Describes at least two aspects of Progressive Era thinking reflected in the settlement house movement (e.g., environmental explanations for poverty, belief in data-driven reform, moral responsibility of the middle class).

Provides accurate examples of Hull House programmes.

5 marks:

Demonstrates analysis of how Hull House practices embodied these wider reform ideas (e.g., collecting social surveys to influence legislation; offering educational and cultural programmes to foster assimilation and community cohesion).

6 marks:

Presents a well-structured argument showing insight into the relationship between Progressive social ideals and immigrant support work.

Integrates specific, accurate evidence (e.g., recreational clubs, job-placement services, arts programmes, civic classes) and clearly explains the link between reform philosophy and practical action.