AP Syllabus focus:

‘Some argued laissez-faire and competition encouraged long-run growth and opposed government intervention during economic downturns.’

Debates over the government’s economic role intensified during the Gilded Age, as rapid industrialization, recurring financial crises, and rising inequality sharpened divides between laissez-faire advocates and intervention supporters.

Laissez-Faire vs. Intervention during Economic Downturns

The Gilded Age Economic Context

The period from 1865 to 1898 witnessed repeated financial panics, heightened volatility in credit markets, and deepening cycles of boom and bust. Industrial expansion generated unprecedented wealth but also exposed structural weaknesses in banking, railroads, and speculative investment. These conditions shaped intense national debates about whether government should remain hands-off or intervene to stabilize the economy. Many political and business leaders defended laissez-faire—the idea that minimal government involvement allowed competition to drive innovation and long-term growth—while others argued that downturns demanded government action to protect workers, farmers, and small businesses.

Laissez-Faire Ideology and Its Intellectual Roots

Laissez-faire thinking drew heavily on classical economic theories that emphasized supply, demand, and market self-regulation. Proponents believed that competition naturally allocated resources efficiently and that any government interference—through regulation, subsidies, or emergency relief—would distort markets, slow growth, and encourage dependency.

Laissez-faire: An economic philosophy asserting that markets function best with minimal government regulation, allowing competition to guide economic outcomes.

Supporters frequently invoked natural law arguments, claiming that economic inequalities reflected differences in talent, effort, or efficiency. Many linked these ideas to emerging Social Darwinist interpretations, although these were not universally embraced even among laissez-faire advocates. They insisted that downturns, while painful, corrected overinvestment and speculation, paving the way for renewed expansion. One key argument held that government intervention might prevent necessary market adjustments, ultimately deepening or prolonging recessions.

After these ideas gained traction, critics began to associate laissez-faire with corporate dominance, but defenders insisted it promoted long-run national prosperity, aligning closely with Republican economic priorities during much of the Gilded Age.

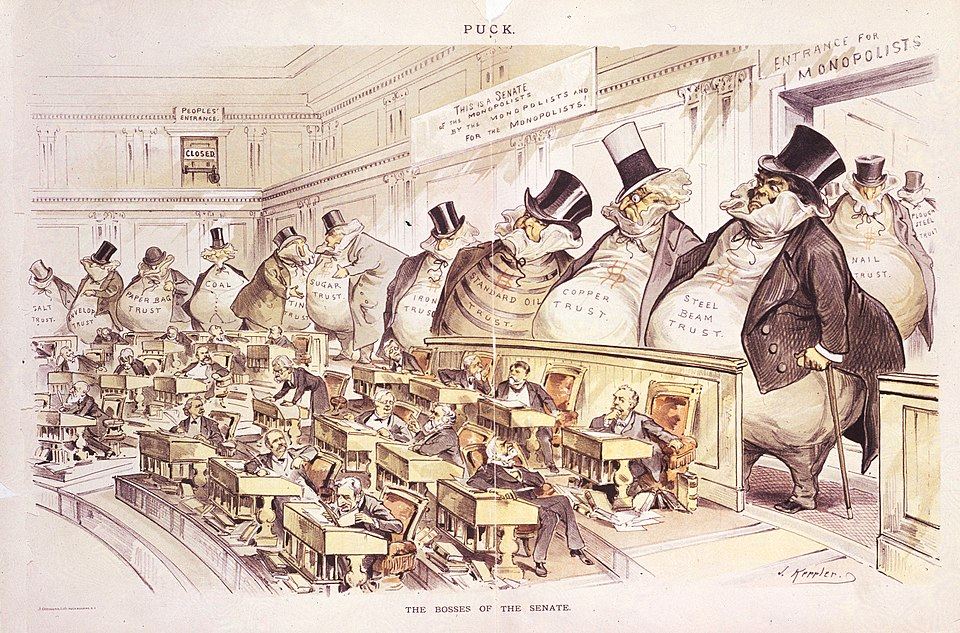

This cartoon illustrates contemporary concerns that trusts and monopolies dominated Congress, portraying giant industry “bosses” looming over senators to symbolize corporate power under laissez-faire politics. The depiction reinforces how critics linked concentrated wealth to political influence. Extra labeled industries appear but align with the theme of monopolistic dominance. Source.

Government Intervention Advocates: Motivations and Arguments

Although laissez-faire was dominant, a growing number of reformers, labor leaders, and farmers called for some level of intervention. They contended that unregulated capitalism produced instability that disproportionately harmed ordinary Americans. Economic downturns often resulted in unemployment, wage cuts, farm foreclosures, and decreased consumer spending. These consequences spurred arguments for federal responsibility in stabilizing markets, regulating powerful corporations, and safeguarding public welfare.

Interventionists emphasized several recurring concerns:

Market consolidation created monopolies and trusts that limited competition and manipulated prices.

Bank failures erased personal savings, amplifying calls for stronger financial oversight.

Unemployment during downturns left workers vulnerable without a social safety net.

Railroad speculation contributed to crises such as the Panic of 1873, prompting demands for regulatory oversight.

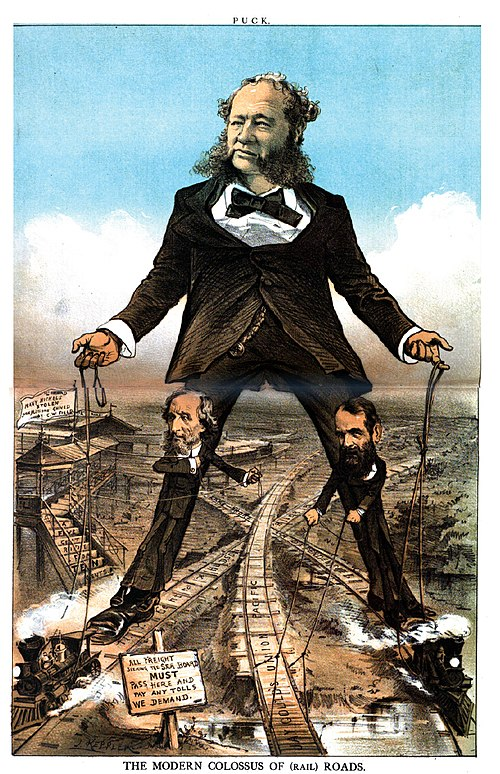

This cartoon portrays William Henry Vanderbilt towering over railroad networks to illustrate the extraordinary influence of rail monopolies during the Gilded Age. The sign declaring that all freight must pass and pay whatever tolls are demanded reflects public concerns about unregulated corporate power. Extra labels identifying tycoons and companies appear but reinforce debates over railroad dominance. Source.

Reform-minded groups—including the Knights of Labor, the Farmers’ Alliances, and later the Populists—pressed for changes such as railroad regulation, expanded currency supply, and federal reforms to curb speculative excess. Their arguments framed downturns as evidence that government had to act when market forces failed to protect the public.

Recurring Economic Crises and Shifting Political Debates

Gilded Age downturns, particularly the Panic of 1873 and the Panic of 1893, intensified debate over the government’s responsibility. These crises triggered bank failures, widespread unemployment, and severe contractions in industry and agriculture. Each downturn strengthened claims that laissez-faire policies were insufficient, yet strong political resistance persisted.

Key political debates included:

Currency and monetary policy, especially disputes over gold vs. silver as a basis for money supply.

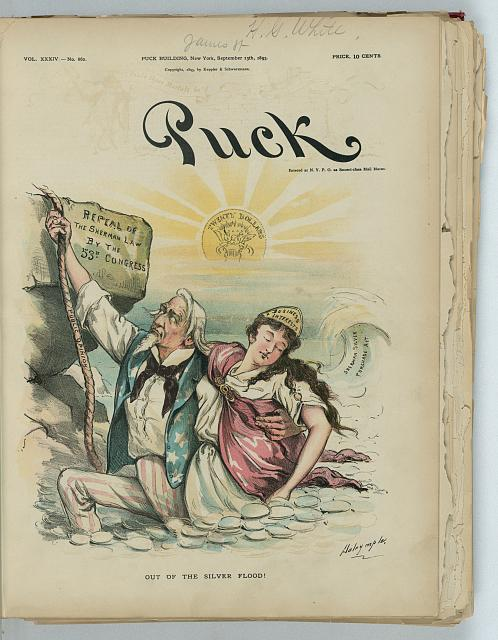

This illustration dramatizes the monetary-policy struggles of the 1890s by depicting Uncle Sam rescuing “Business Interests” from a rising flood of silver coins. The scene reflects concerns that silver-based policies destabilized the economy and portrays repeal efforts as restoring stability. Additional imagery about the gold coin and Sherman Law expands detail but supports the topic’s focus on currency debates. Source.

Tariff policy, with high tariffs defended as growth-promoting and critics arguing they enriched corporations at consumers’ expense.

Regulation of railroads, which many saw as essential given their monopoly power.

Even modest interventions, such as the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887, reflected growing concern about corporate abuses but remained limited in scope due to persistent laissez-faire sentiment.

Business Leaders and the Defense of Nonintervention

Many industrialists and financiers argued that downturns were natural aspects of the business cycle. They claimed that voluntary charitable efforts—not federal policy—should support the poor. Their defense of laissez-faire rested on several core beliefs:

Government could not manage complex economic forces more effectively than markets.

Intervention would undermine innovation and investment.

Economic cycles ultimately strengthened the economy by eliminating inefficient firms.

The belief that competition generated long-run growth helped justify resistance to regulatory reforms, even as public frustration mounted.

Workers, Farmers, and the Push for a More Active Government

Workers and farmers, whose livelihoods were most vulnerable during downturns, increasingly demanded regulatory mechanisms to curb abuses of corporate power. Their critiques shaped new political movements that challenged laissez-faire orthodoxy. They argued that:

Market self-regulation failed to prevent exploitation and instability.

Government had an obligation to intervene when corporate practices threatened economic fairness.

Collective action, through unions or political mobilization, could pressure policymakers to adopt more equitable economic frameworks.

These demands reflected deep social tensions generated by industrial capitalism and set the stage for future Progressive Era reforms.

Interaction of Ideas and Long-Term Significance

The clash between laissez-faire and interventionist views during the Gilded Age created the ideological foundation for twentieth-century debates over economic policy. Although laissez-faire dominated at the time, rising criticism and organized activism highlighted the limitations of nonintervention during downturns. These tensions would soon influence major reforms in banking, labor, and antitrust policy.

FAQ

Many believed downturns eliminated weak or inefficient firms, allowing stronger ones to dominate and thus making the economy more efficient over time.

Supporters also argued that recessions corrected speculative excesses, stabilising prices and investment after periods of overexpansion.

Some business leaders framed downturns as temporary disruptions that disciplined markets and encouraged more rational, long-term decision-making.

Politicians feared that intervention would expand federal power in ways that threatened states’ rights and individual economic freedom.

Laissez-faire ideas were deeply intertwined with party identity — particularly for many Republicans — who associated intervention with corruption or favouritism.

There was widespread scepticism about whether government possessed the expertise to manage complex industrial markets effectively.

Labour groups argued that laissez-faire ignored the realities of wage dependency, leaving workers unprotected during unemployment or wage cuts.

They highlighted the imbalance of power between large corporations and individual workers, contending that “voluntary charity” was insufficient to address widespread hardship.

Unions also maintained that if the government supported business expansion through subsidies or land grants, it had a responsibility to protect workers during downturns.

Monetary debates centred on whether expanding the money supply would relieve economic pressure. Supporters of silver believed inflation would raise crop prices and ease debt burdens.

Opponents argued that loosening the supply would destabilise credit markets, making downturns worse.

These disputes revealed deeper disagreements over government responsibility: intervene to ease hardship, or maintain a stable monetary foundation even at social cost.

Economic crises eroded trust in the ability of markets to self-regulate, increasing support for modest regulation, especially of railroads and banking.

Urban workers, farmers, and small businesses circulated petitions, joined reform movements, and backed candidates advocating economic oversight.

While governments acted only cautiously, public pressure demonstrated that laissez-faire was not universally accepted and foreshadowed later Progressive reforms.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one reason why supporters of laissez-faire economics in the late nineteenth century opposed government intervention during economic downturns.

Mark scheme:

• 1 mark for identifying a valid reason (e.g., belief that markets self-correct, concern that intervention distorts competition).

• 1 mark for explaining how this reason relates to laissez-faire principles (e.g., minimal interference preserves natural market forces).

• 1 mark for linking the explanation to the broader economic context of the Gilded Age (e.g., support from industrial leaders who argued downturns eliminated inefficient firms).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Assess the extent to which economic crises between 1865 and 1898 strengthened calls for increased government intervention in the economy.

Mark scheme:

• 1–2 marks for describing relevant economic crises (e.g., the Panic of 1873 or 1893) and their effects.

• 1–2 marks for explaining how these crises encouraged groups such as workers, farmers, or reformers to demand greater intervention (e.g., regulation of railroads, currency reform, responses to unemployment).

• 1 mark for analysing the limitations of these calls (e.g., continued political resistance from laissez-faire advocates, limited regulatory outcomes like the weak enforcement of the Interstate Commerce Act).

• 1 mark for a supported judgement on the extent to which crises strengthened interventionist sentiment.