AP Syllabus focus:

‘Foreign policymakers increasingly looked beyond U.S. borders to gain influence and access markets and natural resources in the Pacific, Asia, and Latin America.’

The late nineteenth century saw U.S. leaders pursue overseas commercial and strategic opportunities as industrial growth created surpluses and intensified demand for foreign markets.

Expanding Foreign Policy Goals in an Industrial Era

Foreign policymakers after the Civil War increasingly viewed international engagement as essential to sustaining industrial capitalism, ensuring access to raw materials, and securing new customers for manufactured goods. Rapid technological and economic change strengthened confidence that the United States could compete with European empires, encouraging a more assertive global posture. Leaders argued that expanding influence abroad would reinforce national security, stabilize economic growth, and elevate the country to great-power status.

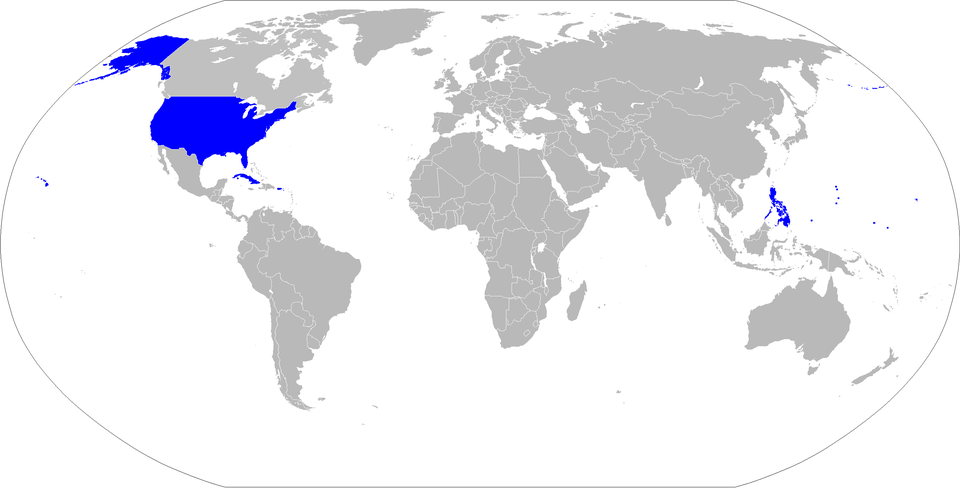

This map shows the United States and its overseas possessions around 1898–1902, including Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines, illustrating the expanding reach of U.S. economic and strategic influence. It visually connects the Caribbean and Pacific regions targeted for access to markets, resources, and naval positioning. The map extends slightly past the AP period but remains valuable for understanding outcomes of late nineteenth-century expansion. Source.

Economic Motivations for Overseas Markets

Industrial expansion produced abundant goods that exceeded domestic consumption. Policymakers and business leaders therefore emphasized the importance of cultivating overseas markets, especially in regions where European powers already operated.

Manufacturers sought new consumers for textiles, machinery, processed foods, and metal goods.

Investors aimed to channel surplus capital into international railroad, mining, and agricultural development.

Merchants supported diplomatic pressure to open ports and reduce trade barriers.

As the United States entered global competition, economic policymakers promoted commercial treaties, tariff negotiations, and diplomatic missions to improve foreign market access.

Strategic and Ideological Drivers of Expansion

Beyond commerce, foreign policy leaders believed a more activist stance would strengthen national security. Overseas coaling stations and naval access, they argued, would enable the nation’s expanding merchant fleet and fortified navy to operate worldwide. The push for influence aligned with broader ideological trends, including American exceptionalism, the belief that the United States had a unique mission to spread political and economic ideals. This ideology also encouraged reformers and policymakers to frame expansion in moral or civilizing terms.

Intellectual Justifications for Overseas Activity

Writers such as Alfred Thayer Mahan popularized arguments linking national greatness to overseas commerce and naval power. His influential ideas supported the belief that nations required global networks of ports, markets, and colonies to thrive.

American exceptionalism: The belief that the United States has a unique mission to promote its political, economic, and cultural values globally.

These arguments resonated with policymakers seeking to justify expanded diplomatic and commercial engagement. Many connected industrial strength to international responsibility, reinforcing political support for outward-looking strategies.

At the same time, Social Darwinist thinking—though controversial—gave some Americans a pseudo-scientific rationale for competition among nations. Advocates used such claims to argue that outward expansion demonstrated national vigor, while restraint signaled weakness.

The Pacific: Securing Access and Influence

Policymakers looked first to the Pacific Rim, an area seen as pivotal for commercial access to Asia.

The annexation-oriented relationship with Hawaiʻi evolved from trade agreements to strategic interest, particularly for naval positioning.

Missionaries, merchants, and investors participated in building economic ties, exerting cultural and financial influence long before formal annexation.

U.S. leaders promoted the Pacific as a gateway to China and Southeast Asian markets, imagining future prosperity dependent on transoceanic commerce.

Asia and the Quest for Trade

Securing access to Asia required navigating the presence of European empires. Diplomatic initiatives sought to protect American commercial opportunities without direct colonization.

Policymakers pushed for open access to major ports.

Negotiations aimed to reduce exclusive privileges enjoyed by European powers.

Informal influence grew through commercial treaties and naval visits.

These steps demonstrated a commitment to global engagement as a means of economic growth and strategic positioning.

Latin America: Commerce, Pan-Americanism, and Intervention

Foreign policymakers simultaneously sought to expand influence in Latin America, where political instability and European interest heightened U.S. concerns. Economic policymakers viewed the region as a natural sphere for American trade, investment, and diplomatic leadership.

U.S. merchants deepened commercial links through the Caribbean and South America.

Investors financed mining, agricultural enterprises, and infrastructure projects.

Diplomats promoted U.S.-led economic cooperation to diminish European involvement.

Pan-Americanism and Regional Leadership

The movement for Pan-Americanism encouraged cooperation among nations in the Western Hemisphere under U.S. leadership.

This photograph depicts delegates at the Pan American Financial Conference of 1915, where representatives from across the hemisphere met to discuss financial and commercial cooperation. It provides a concrete visual example of Pan-American diplomacy that grew from late nineteenth-century efforts to expand U.S. economic influence. Although slightly outside the AP Period 6 timeframe, it directly illustrates the kinds of multilateral engagements shaped by earlier foreign policy developments. Source.

Pan-Americanism: A diplomatic and economic movement promoting cooperation among Western Hemisphere nations under significant U.S. leadership.

Advocates framed hemispheric collaboration as mutually beneficial, though it often served U.S. commercial priorities.

Natural Resources and Strategic Access

As industrial growth accelerated, policymakers increasingly prioritized regions rich in natural resources, including minerals, timber, sugar, and agricultural goods. Diplomatic negotiations and commercial agreements aimed to secure reliable supplies.

Caribbean sugar production became central to trade discussions.

Mining concessions in Latin America attracted U.S. investors.

Pacific access supported the import of raw materials critical for manufacturing.

Natural resource acquisition reinforced perceptions that international engagement was indispensable to sustaining industrial output and economic stability.

Diplomatic Tools for Expanding Influence

Policymakers used a variety of strategies to increase U.S. reach abroad:

Trade agreements that lowered barriers and opened markets

Naval expansion to protect shipping lanes

Investment promotion to link foreign development to U.S. capital

Territorial acquisition debates, often tied to strategic or commercial goals

Foreign policy reflected a blend of diplomacy, commercial ambition, and strategic calculation that positioned the United States as an emerging global power by the late nineteenth century.

FAQ

Improvements in steamship design and the global spread of telegraph cables allowed American businesses and diplomats to operate more quickly and reliably across long distances.

These technologies reduced the cost and risk of international trade, making foreign markets more accessible.

Steamships cut journey times, enabling regular commercial routes.

Telegraph lines let companies coordinate trade and investment in real time.

Together, they made expansion abroad increasingly feasible for policymakers and merchants.

American merchants, bankers, and investors often acted as informal agents of expansion by establishing early economic ties in the Pacific and Latin America.

These private networks:

Provided policymakers with on-the-ground intelligence about commercial opportunities.

Demonstrated that foreign ventures could be profitable, strengthening political arguments for diplomatic involvement.

Pressured officials to secure treaties, naval protection, or favourable tariffs to safeguard investments.

Coaling stations were essential refuelling points for steam-powered naval and merchant vessels, making them strategically valuable.

They allowed the United States to:

Maintain a naval presence far from the mainland.

Protect commercial shipping routes.

Support rapid military deployment if needed.

These stations strengthened America’s capacity to operate globally, reinforcing ambitions for economic and strategic influence.

Missionaries often established long-standing community relationships, schools, and churches, creating cultural links that preceded formal political involvement.

Their presence:

Increased American visibility in local societies.

Encouraged the spread of English-language education and U.S. cultural norms.

Provided justification for diplomatic or naval intervention when Americans abroad were perceived to be at risk.

Although not official policy, such activity helped normalise U.S. influence in the region.

American leaders worried that European powers would dominate territories and markets that the United States hoped to access.

In response, policymakers:

Advocated more assertive diplomacy to prevent exclusion from profitable regions.

Supported naval modernisation to project power abroad.

Promoted hemispheric cooperation in the Americas as a way to limit European involvement.

These concerns helped accelerate the shift from inward-looking policies to broader international engagement.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify and briefly explain one reason why United States policymakers in the late nineteenth century sought increased involvement in overseas markets.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying a valid reason (e.g., access to new markets, securing natural resources, competing with European powers, strategic naval expansion).

1 mark for explaining how this reason motivated policymakers (e.g., industrial overproduction required new consumers; raw materials supported manufacturing).

1 mark for linking the reason specifically to the context of the late nineteenth century (e.g., rapid industrialisation created economic pressure for global commercial expansion).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Explain how United States foreign policy between 1865 and 1898 reflected growing economic and strategic ambitions in the Pacific and Latin America.

Mark scheme:

1–2 marks for describing economic motivations, such as seeking access to foreign markets, investment opportunities, or natural resources.

1–2 marks for describing strategic motivations, such as acquiring naval bases or countering European imperial influence.

1–2 marks for using specific examples to illustrate the explanation (e.g., closer ties with Hawai‘i, attempts to expand influence in Latin America, pursuit of commercial treaties, interest in Asian trade).