AP Syllabus focus:

‘Economic instability encouraged agrarian activists to form the People’s (Populist) Party and demand stronger government regulation of the economy.’

Economic volatility in the late nineteenth century prompted widespread agrarian activism, culminating in the creation of the People’s (Populist) Party, which sought substantial government regulation to counter corporate power.

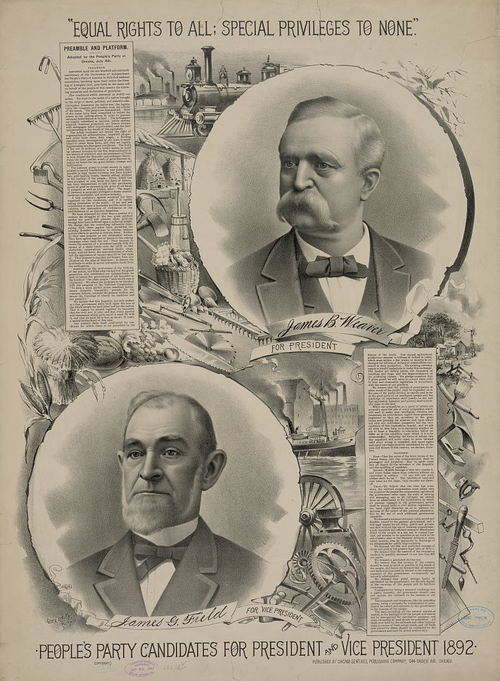

This campaign poster depicts the 1892 People’s (Populist) Party presidential ticket, visually demonstrating the party’s emergence as a national third-party movement. It reinforces how Populists sought to challenge the major parties through organized electoral action. Additional slogans and decorative elements appear that extend beyond the syllabus focus but help convey period political style. Source.

The Roots of Economic Instability

Farmers in the 1880s and 1890s faced chronic instability as global markets and national infrastructure evolved. Falling crop prices undermined rural incomes, while railroad freight rates, grain elevator fees, and loan interest charges tightened financial pressure. Many farmers believed that economic instability resulted not from natural market forces but from political favoritism toward railroads, banks, and large corporations. These concerns fed a growing conviction that the federal government should intervene to regulate monopolistic practices. Agrarian frustration intensified during periods of drought and economic contraction, especially the Panic of 1893, which deepened fears that the nation’s economic system privileged wealthy industrialists at the expense of rural Americans.

Agrarian Organizing Before Populism

Local and Regional Alliances

The Farmers’ Alliances, which emerged across the South and West, became important vehicles for political education and collective action. Although regional alliances developed separate priorities, they shared a commitment to resisting corporate consolidation and stabilizing agricultural markets.

Promotion of cooperative buying and selling to reduce dependence on middlemen.

Advocacy for railroad regulation to curb discriminatory freight rates.

Calls for a more flexible monetary system to ease credit shortages.

From Alliances to National Politics

Activists recognized that economic reforms required national political influence. As alliances grew, their leaders encouraged a shift from regional advocacy toward a unified political front. This transition set the stage for creation of a national third party capable of challenging the established Republican and Democratic parties.

Formation of the People’s (Populist) Party

Motivations for a New Political Organization

By the early 1890s, agrarian activists concluded that the two major parties failed to represent the economic interests of farmers and laborers. Economic instability provided the immediate catalyst for forming a new party dedicated to structural economic reform. The People’s (Populist) Party emerged in 1892 with a platform rooted in democratic expansion and economic regulation.

Key Populist Principles

Populists argued that concentrated economic power threatened the independence of farmers and workers, and they framed political action as the only viable solution. Their platform combined reforms aimed at stabilizing agricultural life with broader proposals to democratize economic decision-making.

Expansion of the money supply through free silver to combat deflation.

Creation of a graduated income tax to reduce inequality and generate federal revenue.

Government ownership or strict regulation of railroads, telegraphs, and telephones.

Adoption of direct democracy measures, including the popular election of senators.

Establishment of postal savings systems and subtreasury plans to provide low-interest credit.

When Populists introduced the term subtreasury, many journalists criticized it as radical, prompting the movement to clarify its intent as a government system that would store crops and issue loans to farmers during periods of low prices.

Subtreasury Plan: A proposed federal program allowing farmers to store crops in government warehouses and receive low-interest loans until market conditions improved.

Many delegates at the 1892 Omaha Convention viewed this system as essential to reducing farmers’ dependence on private lenders.

Populism and Labor

Although rooted in agrarian discontent, the Populist movement attempted to align with industrial workers. Populist leaders argued that farmers and laborers faced similar threats from corporate consolidation and financial manipulation. Efforts to build a cross-class coalition had limited success due to cultural, regional, and racial divides. Still, Populists maintained that broad cooperation was necessary to redesign the national economy.

Populist Electoral Impact

The Election of 1892

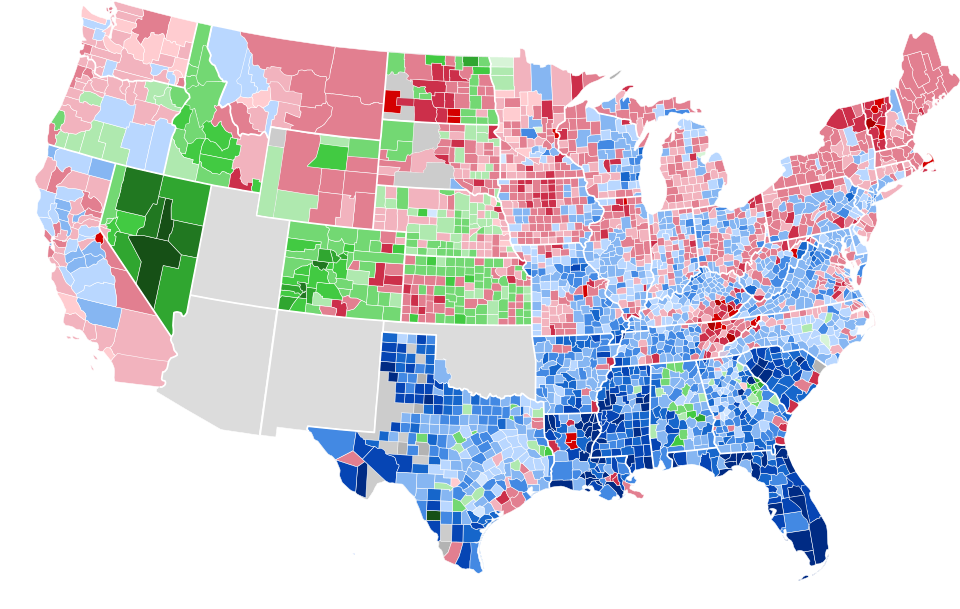

The party gained traction quickly, winning several congressional seats and influencing gubernatorial contests. In the 1892 presidential election, Populist candidate James B. Weaver secured over one million votes and carried multiple Western states.

This county-level electoral map highlights where Populist support for Weaver was concentrated, particularly in the West and parts of the South. It visually reinforces the agrarian geographic base that underpinned Populist political strength. Although it also displays detailed results for Democrats and Republicans, these additional layers help contextualize the Populist position within the broader 1892 political landscape. Source.

The Depression Politics of 1893–1896

The economic crisis following the Panic of 1893 amplified Populist arguments. High unemployment, bank failures, and agricultural collapse validated concerns about unregulated capitalism. Populists pressed for aggressive federal action, particularly monetary expansion and railroad regulation.

The Populist Fusion with Democrats

The 1896 Campaign and Free Silver

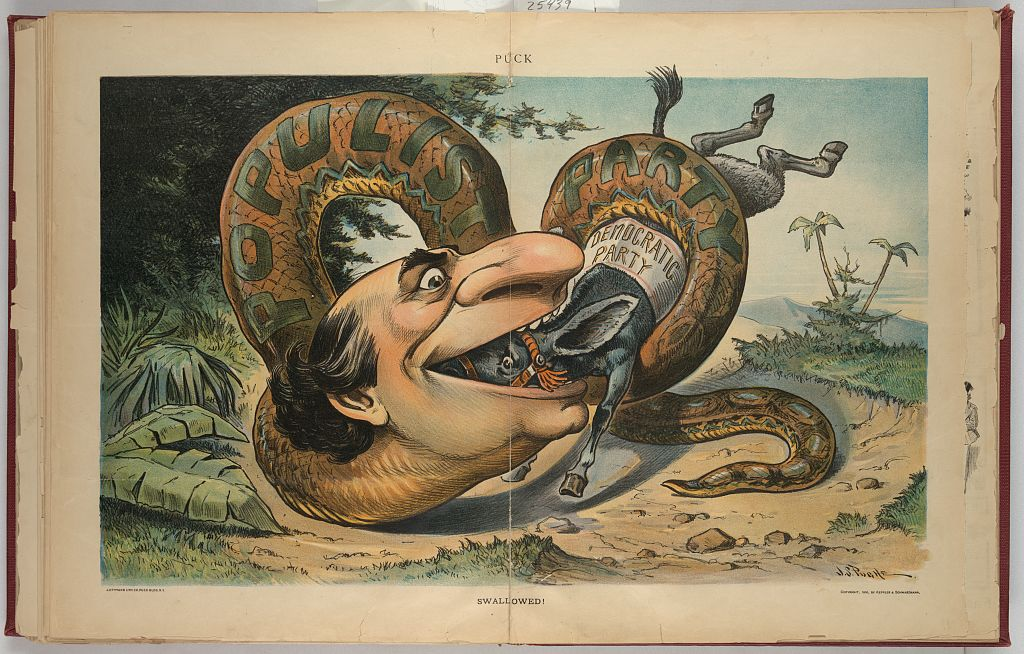

The critical turning point came when Democratic candidate William Jennings Bryan adopted the free silver cause. Populists debated whether to fuse with Democrats or maintain independence. Ultimately, they endorsed Bryan, believing his election could achieve key monetary reforms.

This cartoon dramatizes contemporary anxieties over Populist–Democratic fusion by portraying Bryan as a Populist snake encircling the Democratic donkey. It illustrates fears that the alliance might overwhelm or distort party identities, echoing debates described in the 1896 fusion controversy. The image references the 1900 election and includes period-specific details beyond the syllabus but helps visualize public perceptions of the Populist–Democratic relationship. Source.

Fusion offered short-term political influence.

It risked diluting the distinct Populist agenda.

Internal divisions weakened the party’s grassroots cohesion.

Despite Bryan’s defeat, the election cemented Populism’s role in national debates about economic regulation.

Legacy of the People’s Party

Populism declined as an organized movement after 1896, yet many of its proposals influenced later Progressive reforms. Calls for government regulation of railroads, direct election of senators, and a graduated income tax eventually became national policy. The Populist critique of concentrated economic power shaped twentieth-century debates about the relationship between government and the economy, reflecting the syllabus emphasis on how economic instability encouraged agrarian activists to demand stronger government regulation.

FAQ

Many of the strongest advocates for a national party came from the Southern and Western alliances, but their motivations differed.

Southern Alliance leaders tended to emphasise credit reform and relief from debt peonage, while Western Alliance members prioritised railroad regulation and monetary expansion.

These regional nuances pushed activists to create a unified Populist platform broad enough to accommodate varied grievances without diluting core economic demands.

Populist communication relied on dense local networks fostered through cooperative organisations.

• Alliance lecture circuits spread economic critiques and reform proposals.

• Local newspapers sympathetic to Populism reprinted speeches, convention updates, and editorials.

• Community gatherings, including fairs and farmers’ institutes, served as informal political classrooms.

This grassroots information system allowed Populist ideas to reach isolated rural populations effectively.

Many urban labour groups feared that aligning with an agrarian-led party might sideline industrial issues such as workplace safety, shorter hours, and union recognition.

Labour organisations also worried that rural monetary proposals, like free silver, would not necessarily translate into better wages or working conditions.

Ethnic, racial, and regional tensions further complicated attempts to build a unified labour–farmer coalition.

Populist speakers framed their movement not as radical innovation but as a restoration of democratic principles.

• They emphasised corruption in existing parties to justify creating a new political home.

• Appeals to patriotism, biblical imagery, and agrarian virtue helped normalise reform proposals.

• Speakers often contrasted the “producing classes” with monopolistic elites to present Populism as a moral corrective rather than a disruptive force.

These tactics reduced resistance among voters hesitant to abandon long-standing party loyalties.

Women played crucial roles as organisers, lecturers, and writers, strengthening the movement’s legitimacy.

Female activists highlighted household economic burdens—such as rising consumer prices and lack of credit access—to connect Populist reforms to everyday life.

Their visibility also helped portray the party as a family-centred, community-rooted movement rather than a purely economic protest.

Some women’s advocacy pushed the party toward supporting broader democratic reforms, including increased political participation.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify one economic factor that contributed to the rise of the People’s (Populist) Party in the late nineteenth century and briefly explain how it encouraged agrarian political activism.

Mark scheme

• 1 mark for identifying a relevant economic factor such as falling crop prices, high railroad freight rates, scarcity of credit, or the fallout from the Panic of 1893.

• 1 mark for explaining how this factor harmed farmers (for example, reducing income, increasing debt burdens, or creating market instability).

• 1 mark for connecting the factor to the motivation for political mobilisation (for example, encouraging demands for regulation or prompting support for a new political party).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Explain the main political and economic goals of the People’s (Populist) Party and evaluate how effectively the party challenged the dominance of the two major political parties during the 1890s.

Mark scheme

• 1–2 marks for accurately outlining key Populist goals, such as free silver, government regulation of railroads, income tax reform, or direct election of senators.

• 1–2 marks for explaining why these goals appealed to farmers and labourers experiencing economic instability.

• 1 mark for describing the Populists’ electoral achievements, such as Weaver’s 1892 performance or regional successes in Western states.

• 1 mark for evaluating the party’s effectiveness, which may note limited long-term success, internal divisions, or reliance on fusion with Democrats in 1896.