AP Syllabus focus:

‘Farmers formed local and regional cooperative organizations in response to consolidated agricultural markets and dependence on railroads.’

Farmers in the late nineteenth century organized cooperatives and alliances to counter falling crop prices, rising debts, and exploitative railroad and merchant practices shaping national agricultural markets.

The Rise of Farmer Organization in a Consolidating Market

During the late nineteenth century, American agriculture became increasingly tied to national and international markets, exposing farmers to volatile prices and unequal relationships with railroads, grain elevator operators, and banks. As individual farmers struggled to influence these powerful forces, they turned to collective action through cooperatives and alliances designed to restore economic stability and bargaining power.

Market Consolidation and Farmer Vulnerability

Farmers faced a rapidly consolidating agricultural system in which railroads dominated transportation, grain elevator operators controlled storage, and merchants set credit terms. These conditions created a cycle of dependency that limited autonomy and reduced profits. Many agricultural communities concluded that only organized collective action could counteract these structural disadvantages.

Cooperative: A collectively owned and democratically managed enterprise in which members pool resources to obtain better prices or services than they could individually.

In this context, cooperatives became both an economic strategy and a form of resistance against unequal market power. These organizations helped farmers secure more favorable terms while challenging the dominance of railroad and merchant monopolies.

Early Cooperative Efforts: The Grange

The first widespread attempt to organize farmers came through the National Grange of the Patrons of Husbandry, founded in 1867.

Photograph of Pineland Grange Hall No. 549 in South Carolina, a local meeting hall for members of the National Grange. Buildings like this served as cooperative centers where farmers gathered for education, joint economic action, and social events. The image shows the modest, community-based setting that underpinned larger movements for farmer cooperation and market reform. Source.

While originally a social and educational organization, the Grange soon expanded into economic activism as market pressures intensified.

Granger Cooperatives and Mutual Aid

Granger cooperatives focused on reducing dependence on intermediaries. They operated through several initiatives:

Collective purchasing of machinery and supplies to lower costs.

Shared grain elevators to bypass private storage operators.

Cooperative stores that offered goods at reduced prices.

Lobbying campaigns targeting railroad regulations.

These ventures varied in success but demonstrated the potential of organized economic action. Importantly, they introduced farmers to a shared political vocabulary centered on fairness, transparency, and resistance to monopoly power.

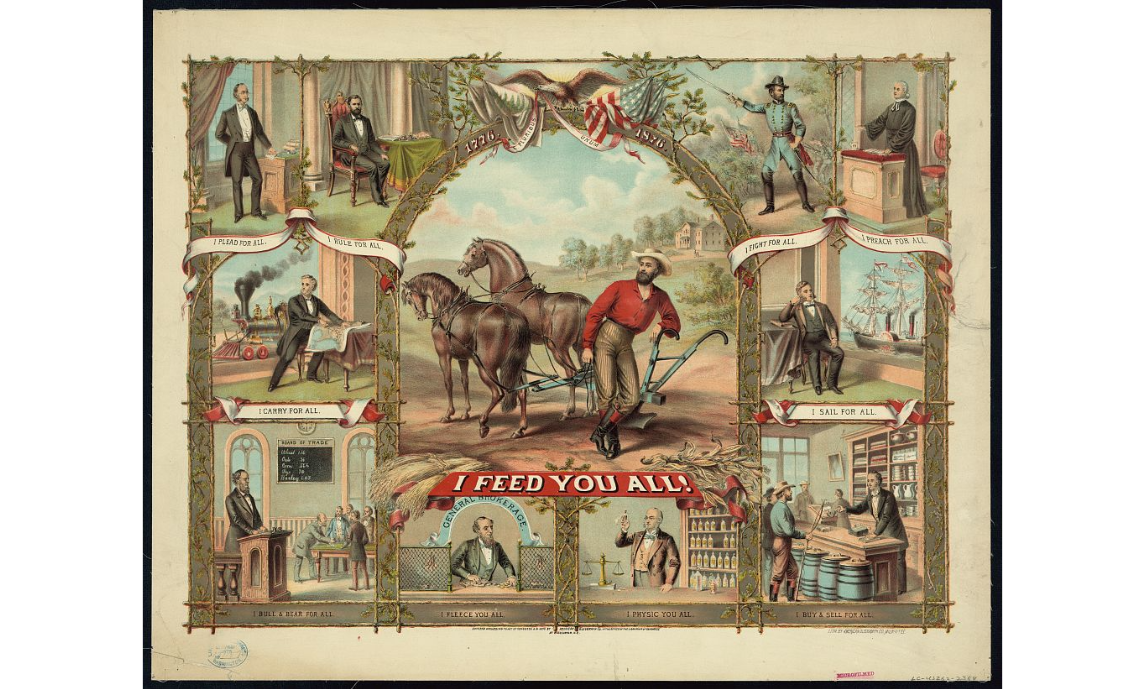

“I Feed You All!” is a color lithograph inspired by the Grange that places a farmer with his plow and team at the center of American economic life. Surrounding vignettes portray other professions—lawyers, merchants, soldiers, railroad owners—each labeled to emphasize their dependence on the farmer’s labor. Some details extend beyond the syllabus, but all reinforce farmers’ critiques of monopoly power and their motivation for cooperative organizing. Source.

A sentence is required here before the next definition to maintain appropriate spacing and avoid consecutive definition blocks.

Monopoly: Exclusive control over a commodity or service, allowing a company or entity to set prices and limit competition.

The Farmers’ Alliances and Expanded Regional Mobilization

By the 1880s, new organizations emerged that were more ambitious and structurally advanced than the Grange. The Southern Farmers’ Alliance, Northwestern Farmers’ Alliance, and Colored Farmers’ Alliance together represented millions of agricultural workers confronting shared economic pressures.

Organizational Structure and Goals

The Alliances combined education, economic cooperation, and political advocacy. Their leadership promoted the idea that farmers could only improve their economic position by transforming market structures rather than adapting individually to unfavorable conditions.

Key priorities included:

Reducing interest rates through cooperative credit systems.

Improving transportation costs by negotiating collectively with railroads.

Establishing warehouses to store crops until prices improved, limiting middlemen’s leverage.

Encouraging scientific farming and education to increase efficiency.

The regional Alliances shared common goals but adjusted strategies to local needs, especially where racial and economic differences shaped farming communities.

The Subtreasury Plan: A Transformative Economic Vision

One of the most ambitious proposals came from the Southern Farmers’ Alliance: the Subtreasury Plan, which envisioned federal government involvement to help stabilize agricultural markets. Under this plan, farmers would store crops in federally managed warehouses and receive low-interest loans based on the stored value. They could then sell crops when market conditions improved.

Significance of the Subtreasury Plan

Although never adopted, the plan marked a significant shift toward advocating for structural federal reform rather than solely local economic solutions. It also reflected growing frustration with private credit systems and railroad monopolies. The plan laid ideological groundwork for later political movements demanding stronger governmental regulation.

Racial Dynamics and Parallel Organizing

The Colored Farmers’ Alliance, formed in response to segregation and exclusion from white-dominated Alliances, became a major organization for Black farmers seeking economic autonomy. While limited by discriminatory systems and fewer resources, it advanced cooperative strategies and community uplift. These parallel movements reveal the deeply segregated nature of agricultural labor but also the shared pressures that motivated collective action.

Political Mobilization and the Legacy of Farmer Organization

By the late 1880s and early 1890s, the Farmers’ Alliances transitioned increasingly into political activism. Their critiques of concentrated economic power inspired the formation of the People’s (Populist) Party, which pushed for federal regulation of railroads, bank reforms, and monetary policies benefiting indebted farmers.

Long-Term Impact

Even though many cooperative ventures struggled financially and political victories were limited, the organizing efforts of farmers fundamentally reshaped national debates about markets, regulation, and economic justice. They challenged the assumption that agricultural producers should remain isolated participants in vast commercial systems and instead advanced the idea that democratic cooperation could counterbalance corporate consolidation.

Farmer organizing during this period stands as a major response to the structural pressures of a consolidating national market, demonstrating how cooperation, alliances, and political mobilization emerged from the crises of the Gilded Age agricultural economy.

FAQ

Farmers faced highly volatile crop prices caused by global overproduction, leaving them unable to predict annual income. Individually, they lacked the bargaining leverage to negotiate fair rates for storage, transport, or credit.

Cooperatives allowed communities to pool risk and resources, creating more predictable costs and reducing reliance on intermediaries who often set unfavourable terms.

They also enabled farmers to share information about market conditions, helping them make more strategic decisions about when and where to sell crops.

Cooperative purchasing clubs negotiated bulk-buying arrangements for tools, fertiliser, and household goods, allowing members to obtain lower prices than they could secure on their own.

Merchants viewed these clubs as a direct threat because:

Farmers could bypass local stores entirely.

Bulk purchasing reduced the merchants’ traditional profit margins.

They undermined the credit-based system merchants used to keep farmers indebted and dependent.

Many cooperatives lacked experienced managers, leading to poor accounting and difficulties negotiating favourable shipping or wholesale agreements.

Railroads and grain elevator companies sometimes retaliated by raising rates or refusing service, pressuring cooperatives into financial difficulty.

Additionally, cooperatives often depended on members maintaining strict loyalty, yet some farmers defected when private companies temporarily offered lower prices to weaken the cooperative’s market influence.

Alliance lecturers travelled widely, teaching farmers how national markets operated and why price fluctuations reflected broader structural issues rather than personal failings.

Educational programmes covered:

How credit and debt systems functioned.

Crop diversification strategies.

The mechanics of railroad rate-setting.

The benefits of collective action in market negotiations.

This emphasis on economic literacy helped transform local frustrations into coordinated reform efforts.

Cooperatives often became centres of social and cultural life, hosting gatherings, lectures, and events that fostered stronger community identity.

They encouraged democratic participation by involving members in decision-making, budgeting, and elections, reinforcing civic skills that later shaped political activism.

By building networks across counties and states, cooperatives helped rural Americans imagine themselves as part of a broader movement rather than isolated local producers.

Practice Questions

Explain one reason why farmers in the late nineteenth century formed cooperative organisations such as the Grange. (1–3 marks)

Question 1: Explain one reason why farmers in the late nineteenth century formed cooperative organisations such as the Grange. (1–3 marks)

1 mark: Identifies a valid reason (e.g., to reduce dependence on railroads or merchants).

2 marks: Provides a brief explanation showing why this reason motivated farmers.

3 marks: Provides a clear and developed explanation, explicitly linking farmers’ economic pressures to the appeal of cooperative action.

Examples that gain credit:

Falling crop prices leading to economic hardship.

Railroad monopolies charging high freight rates.

Desire for collective purchasing to lower costs.

Need for shared storage facilities to bypass private grain elevators.

Using your knowledge of the period 1865–1898, analyse how the Farmers’ Alliances sought to challenge the economic power of railroads and merchants. In your answer, provide specific examples of their strategies and aims. (4–6 marks)

Question 2: Analyse how the Farmers’ Alliances sought to challenge the economic power of railroads and merchants. (4–6 marks)

4 marks: Describes at least two strategies used by the Farmers’ Alliances, with some explanation of how these challenged economic power.

5 marks: Offers well-developed analysis with specific detail (e.g., cooperative credit systems, warehouse plans, political lobbying).

6 marks: Provides a comprehensive answer with precise examples, clear analysis of economic structures, and shows strong contextual understanding of the broader market pressures facing farmers.

Points that may earn marks:

Establishing cooperative credit systems to circumvent merchant-controlled credit.

Creating cooperative warehouses to store crops until prices improved.

Advocating regulatory reforms targeting railroad freight rates.

Supporting the Subtreasury Plan as a means of securing low-interest federal loans.

Promoting collective bargaining and education to strengthen farmer solidarity.

Marks are awarded for accurate, relevant, and well-explained historical analysis.