AP Syllabus focus:

‘Improved mechanization increased agricultural production substantially and helped drive down food prices in the late nineteenth century.’

Late nineteenth-century mechanization revolutionized American agriculture by transforming how farmers produced, harvested, and processed crops, dramatically increasing output while intensifying market pressures and lowering consumer food prices nationwide.

Mechanization and Expanding Agricultural Productivity

The post–Civil War decades saw rapid adoption of mechanical farming technologies, which allowed individual farmers to cultivate far more acres than had previously been possible with hand labor or animal-powered tools. Devices such as the mechanical reaper, twine binder, and steel plow became essential to large-scale commercial agriculture, especially in the Midwest and Great Plains.

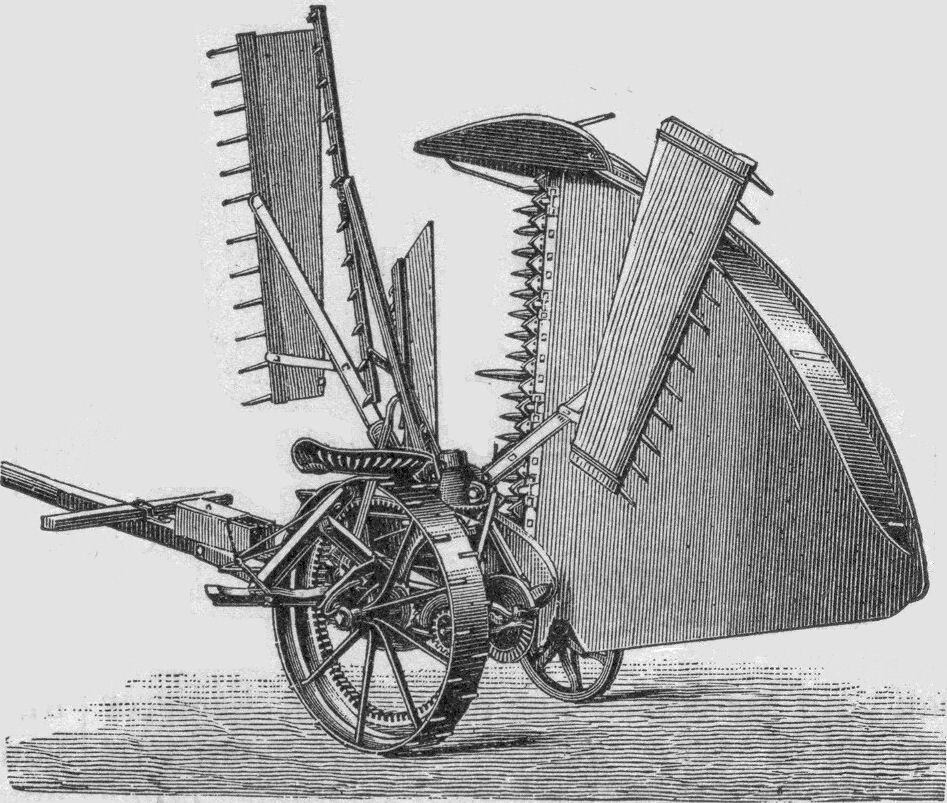

Illustration of a self-rake mechanical reaper showing how horses powered the machine while its blades cut grain and the rake cleared the platform. This design enabled farmers to harvest far more acres than with hand tools, helping drive the surge in agricultural output. The model shown is European but closely resembles American reapers that transformed U.S. grain farming. Source.

These innovations reshaped the rhythms of farm life, intensified seasonal labor demands, and linked farmers more directly to national and international markets.

Key Technologies That Drove Output

Mechanization dramatically reduced the time and labor required to complete essential agricultural tasks. Farmers could now prepare land, plant seed, and harvest crops with unprecedented efficiency.

Mechanical reapers increased harvesting speed, enabling farmers to reap many more acres in a single season.

Twine binders bundled grain automatically, eliminating labor-intensive hand binding.

Steam-powered threshers separated grain from chaff rapidly, supporting mass production.

A steam-powered threshing machine at work on Centinela Ranch around 1900, automating separation of crop from plant material. Though shown processing beans, the machinery reflects the same mechanized threshing that expanded grain production. The scene illustrates how steam engines replaced large teams of laborers in processing tasks. Source.

Steel plows cut through dense prairie sod, facilitating rapid expansion of farmland.

Improved seed drills planted rows more accurately, boosting crop yields.

These innovations enabled farmers to scale up operations and specialize in commodity crops such as wheat and corn. As a result, agricultural productivity surged across the late nineteenth century.

Market Effects of Rising Output

Mechanization’s most notable economic consequence was its effect on food prices, which fell steadily as production soared. This development reflected basic supply-driven market dynamics: when output increased faster than consumer demand, prices declined. More farmers entered commercial farming, producing for distant rather than purely local markets. National railroad networks amplified the effect by moving crops quickly to growing urban centers and eastern ports.

Supply: The total quantity of a good that producers are willing and able to offer at various prices in a market.

The expanding agricultural supply reduced consumer prices for staple foods like wheat, corn, and oats. Urban Americans benefited from cheaper diets, while farmers increasingly faced volatile incomes.

The growth of a national market meant that a bumper harvest in one region could depress prices across the country. Thus, even as total output increased, many producers found themselves trapped in cycles of overproduction, declining prices, and rising debt.

Regional Patterns and the Role of the Great Plains

Mechanization aligned closely with the settlement of the Great Plains, an area uniquely suited to mechanized agriculture because of its vast, relatively flat expanses.

A combine harvester operating in a California wheat field in 1938, performing cutting and threshing in a continuous process. The image illustrates the long-term trajectory of mechanization toward large-scale, labor-efficient grain farming. Although slightly later than the APUSH Period 6 era, it visually reinforces the mechanized practices that began in the late nineteenth century. Source.

Homesteaders and commercial farmers adopted mechanized tools out of necessity—labor shortages, distant markets, and environmental conditions made intensive manual farming impractical. Mechanization also supported monoculture farming, where families planted large areas of a single cash crop to maximize profits and meet mortgage obligations.

Shifting Labor Demands

As machines replaced many traditional tasks, the nature of farm labor shifted. Households required fewer hired hands except during peak harvesting seasons. Seasonal laborers, including immigrants and migrant workers, often filled these short-term needs. Children continued to contribute substantially to farm work, though mechanization changed the tasks they performed.

Farmwomen’s labor also evolved; while they took on fewer field duties, they increasingly managed household economies tied to market fluctuations, such as poultry production and dairy processing.

The Economic Pressures Behind Falling Food Prices

Mechanization alone did not determine agricultural prices; its effects intersected with broader structural forces. Railroad networks, grain elevator systems, and international trade forged a truly global grain market. American farmers competed with producers in Canada, Russia, and Argentina. When overseas harvests were plentiful, U.S. producers faced even greater downward price pressure.

Expanding railroad mileage allowed grain to reach domestic and international buyers quickly.

Telegraph networks transmitted price information instantly, integrating farmers into world markets.

International grain exchanges linked American output to global supply and demand.

Farmers often borrowed money to purchase expensive machinery, which tied them to creditors and required high-output harvests to remain solvent. As prices fell, many discovered that increased production did not necessarily translate into increased profit.

Mechanization’s Mixed Legacy for Rural America

Mechanization undeniably improved total agricultural production and helped feed a rapidly urbanizing nation. It demonstrated the transformative power of technological change in rural settings and marked a pivotal moment in the transition to modern industrial agriculture. Yet it also exposed farmers to heightened market volatility and debt burdens.

Many farmers recognized that mechanization, while essential for competitive production, generated unintended economic hardships. Their frustrations formed the foundation for later organizational and political responses, including cooperatives, alliances, and eventually the Populist movement—developments explored in other subtopics.

Mechanization thus represented both opportunity and challenge: it expanded the nation’s food supply and fueled economic growth while deepening the structural vulnerabilities of rural producers in a modernizing economy.

FAQ

Mechanisation increased farmers’ need for formal credit because machinery such as reapers and threshers required substantial upfront investment. Many farmers turned to banks, local merchants, or mortgage lenders for loans tied to future crop sales.

This shift deepened farmers’ dependence on credit markets, making them more vulnerable to interest-rate fluctuations and poor harvests.

Mechanisation therefore linked agricultural productivity more closely to financial risk, especially on the Great Plains where machinery was essential for cultivating large plots.

Yes. As machines allowed a single operator to cultivate more acreage, farms tended to grow larger, favouring land consolidation.

Small farmers unable to afford machinery were sometimes forced to sell land or operate as tenants or sharecroppers.

Meanwhile, larger commercial farmers expanded operations, reinforcing a trend towards industrial-scale agriculture in key grain-producing regions.

Mechanisation reduced some forms of women’s field labour but expanded their involvement in managing household-based market activities such as poultry raising and dairying.

Women often took responsibility for bookkeeping, purchasing supplies, and tracking debts associated with machinery costs.

Thus, while mechanisation shifted physical labour patterns, it also increased women’s economic responsibilities within the farm household.

Mechanisation encouraged the rapid breaking of prairie sod, accelerating soil exposure and erosion.

The expansion of wheat monoculture depleted nutrients and created vulnerability to drought.

Farmers also pushed cultivation into marginal lands, increasing ecological strain in semi-arid regions.

While these effects would not fully manifest until the twentieth century, mechanisation laid the foundations for long-term environmental challenges.

Adoption was quickest on the Great Plains, where flat terrain, large farm sizes, and labour scarcity made mechanised tools highly efficient.

In contrast, regions with smaller farms or diversified crops—such as New England—saw slower adoption because machines were less cost-effective and terrain limited efficiency.

Railroad access also shaped adoption rates by determining how easily farmers could sell surplus crops to distant markets.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which mechanisation in the late nineteenth century contributed to falling food prices in the United States.

Mark scheme

Award up to 3 marks:

1 mark for identifying a relevant aspect of mechanisation (e.g., mechanical reapers, steam-powered threshers, improved seed drills).

1 mark for describing how this innovation increased agricultural productivity (e.g., faster harvesting, greater acreage cultivated).

1 mark for linking increased output to falling market prices through greater supply or market integration.

Full marks require a clear causal explanation rather than an isolated statement.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse the extent to which mechanisation transformed farming practices in the United States between 1865 and 1898.

Mark scheme

Award up to 6 marks:

1 mark for identifying specific examples of mechanisation (such as mechanical reapers, steel ploughs, twine binders, or steam-powered threshers).

1–2 marks for explaining how these technologies changed day-to-day farming practices (e.g., increased acreage farmed, reduced labour requirements, changes to harvesting or processing).

1–2 marks for assessing broader economic or social effects (e.g., integration into national markets, increased debt due to machinery costs, overproduction leading to price drops).

1 mark for a judgement that evaluates the extent of transformation (e.g., noting limits to mechanisation, regional variation, or continued reliance on seasonal labour).

Full marks require both detailed evidence and a clear analytical argument.