AP Syllabus focus:

‘Businesses used technological innovations and greater access to natural resources to dramatically increase the production of goods.’

Industrial capitalism accelerated after the Civil War as new technologies and expanded resource extraction transformed production, enabling manufacturers to increase output, scale operations, and penetrate national markets.

Major Drivers of Industrial Output Growth

Expanding Technological Innovation

New technologies were central to the rapid growth of industrial production in the late nineteenth century. Inventors and industrial scientists devised machines and processes that radically improved manufacturing efficiency. Innovations such as the Bessemer process, which enabled the mass production of steel through rapid air blasting to remove impurities, allowed industries to scale output at unprecedented levels.

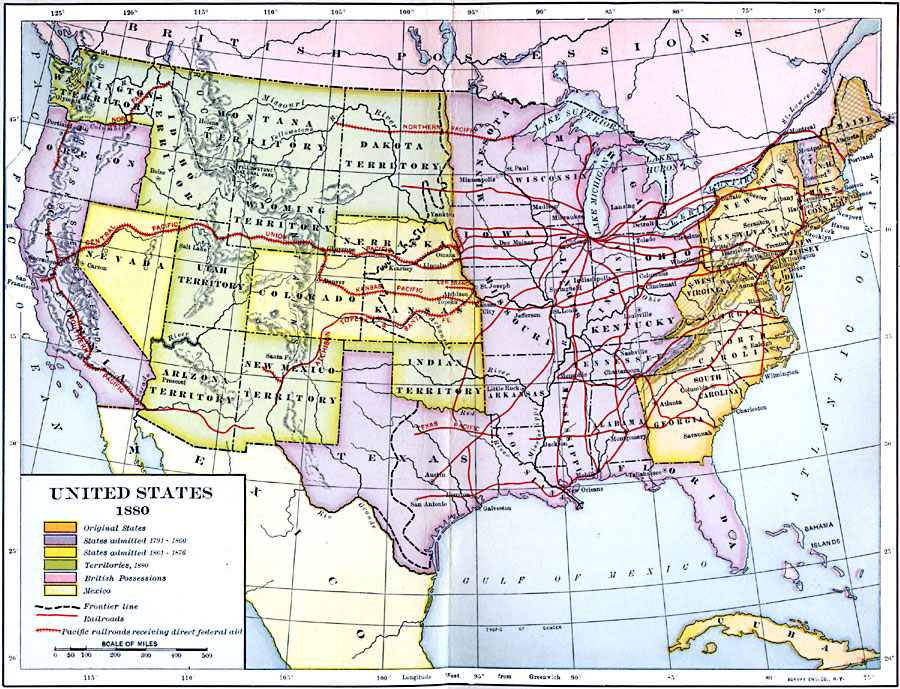

Map of the United States in 1880 showing major railroad lines stretching across the country and linking eastern industrial centers to western resources and markets. The color coding introduces political context beyond the AP requirement but does not add new concepts students must learn. The dense rail network visually reinforces how transportation underpinned mass production and nationwide distribution. Source.

Bessemer process: A steelmaking method that forced air through molten iron to remove impurities quickly, enabling inexpensive mass steel production.

These innovations fostered the expansion of factories across the Northeast and Midwest, allowing businesses to replace small-scale workshops with centralized, mechanized production. As mechanization advanced, firms reorganized workflow to maximize throughput, increase uniformity, and control quality.

Natural Resources and Industrial Growth

A key factor behind rising industrial output was the nation’s abundant and increasingly accessible natural resources. Vast deposits of coal, iron ore, oil, and timber underpinned many of the era’s technological developments. Improved extraction technologies and transportation networks allowed manufacturers to tap into distant resource regions, stimulating both regional and national economic integration.

Natural resources: Raw materials such as coal, iron, timber, and petroleum that fuel industrial processes and support manufacturing expansion.

A sentence here maintains the required spacing between definition blocks and continued explanation.

Businesses transformed these inputs into steel, energy, and building materials essential for railroads, factories, and urban development. Every major industrial sector—from textiles to steel to consumer goods—benefited from cheaper, more reliable access to raw materials.

Synergy Between Innovation and Resource Access

The relationship between innovation and natural resources was mutually reinforcing. New technologies required reliable supplies of raw materials, while improved extraction and refining methods stimulated further technological experimentation. For instance, petroleum refining expanded rapidly after innovators devised more efficient distillation processes, which in turn supported the growth of kerosene and lubricants critical to machinery.

Industrial Applications of New Technologies

Mechanization and Factory Productivity

Mechanization reshaped how goods were produced. Factories adopted steam-powered and later electrical machinery to increase output, reduce labor costs, and maintain consistent production schedules. Steam engines powered textile looms, metal presses, and woodworking machinery, allowing continuous operation independent of human strength or environmental conditions.

Key effects of mechanization included:

Higher output per worker, reducing unit costs for manufacturers.

Standardized production, making goods more interchangeable and reliable.

Greater factory size, enabling businesses to centralize labor and machinery in large industrial complexes.

Longer working hours, as power sources replaced daylight as the main determinant of production time.

Transportation Innovations and Market Expansion

Transportation technologies amplified industrial growth by connecting raw materials, factories, and consumers. The spread of railroads made it possible to ship bulky resources from remote regions to industrial centers and to distribute finished goods across the nation.

Railroad expansion contributed to output growth through:

National integration of resource supplies.

Faster, cheaper, and more predictable shipment of goods.

Creation of standardized time zones that coordinated industrial scheduling.

Support for urbanization as cities grew around major rail hubs.

Energy Innovations

Energy production also transformed during this period. Coal remained the dominant fuel, powering steam engines and metal furnaces. Meanwhile, the rise of petroleum refining created new energy markets and opened opportunities for industrial machinery requiring lubrication and fuel.

These improvements enabled factories to run larger machines, increase production hours, and reduce dependence on local environmental conditions such as river flow or wind supply.

Business Strategies Enabled by Higher Industrial Output

Scaling Operations and Vertical Integration

Larger industrial output encouraged firms to consolidate operations. Business leaders pursued vertical integration, or control over multiple stages of production—from raw material extraction to manufacturing to distribution—to ensure stable input supplies and reduce costs.

Vertical integration: A business strategy in which a company controls several stages of production and distribution to increase efficiency and reduce costs.

A sentence here maintains the required spacing and transitions into further analysis.

Mass Production and Market Reach

Mass production techniques enabled manufacturers to serve national markets, reducing prices and increasing consumer access to goods. Businesses invested in advertising, brand development, and nationwide distribution networks to reach broader markets and secure demand for their expanding output.

Impact on Labor and Industrial Organization

The shift toward mechanized, high-output industry transformed labor systems. Factories required larger workforces, drawn from both rural Americans and immigrants. Supervisory structures expanded, creating new managerial layers tasked with coordinating machinery, labor, and materials.

Broad Consequences of Output Expansion

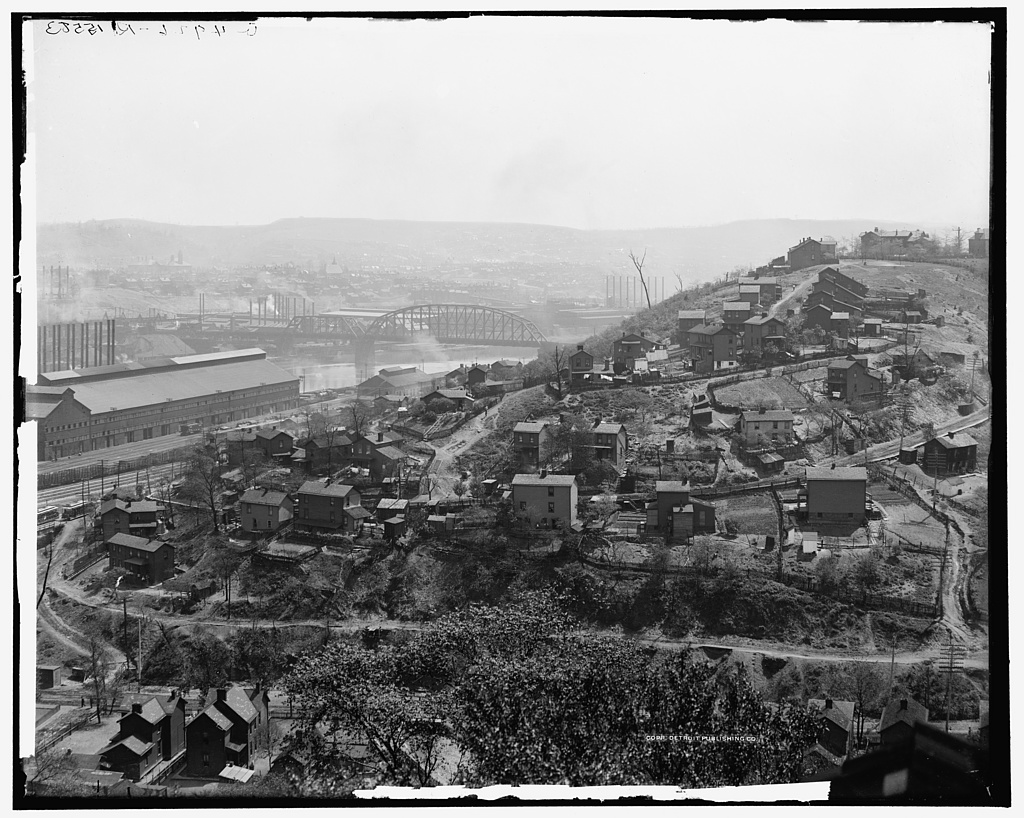

Urban Growth and Regional Specialization

Industrial expansion contributed to rapid urbanization, as workers flocked to cities housing major factories.

Photograph of Homestead Steel Works in Homestead, Pennsylvania, with a large steel mill rising behind densely built workers’ housing. It illustrates how industrial plants shaped the physical and social landscape of surrounding urban communities. Although the dating may extend slightly beyond the AP period, the setting closely reflects Gilded Age industrial environments. Source.

National Economic Transformation

By combining technological innovation with abundant natural resources, the United States laid the groundwork for becoming a leading global industrial power. These changes reshaped everyday life, spurred economic diversification, and fostered a more interconnected national economy.

FAQ

Industrial research laboratories, such as Thomas Edison’s Menlo Park, enabled companies to systematise invention rather than rely on individual experimentation.

They accelerated the refinement of existing technologies and produced commercially viable innovations that supported continuous productivity gains.

Laboratories also strengthened ties between science and industry, allowing firms to adapt processes rapidly and reduce production bottlenecks.

Steel’s versatility made it essential for railways, machinery, bridges, shipbuilding, and urban construction, enabling industries to expand both capacity and scale.

Its high strength–to–weight ratio made it ideal for new industrial and architectural demands, such as multi-storey factories and modern shipping vessels.

Because steel-fed industries multiplied, any improvement in steel output had compounding effects across the wider economy.

Better mining equipment and drilling techniques made previously inaccessible deposits profitable, shifting economic activity toward regions rich in coal, iron ore, and oil.

These regions soon attracted rail investment, labour migration, and factory construction, creating new industrial corridors.

Resource extraction centres often evolved into specialised hubs, shaping distinctive local economies tied to a single resource.

More reliable coal and petroleum supplies freed factories from dependence on natural power sources such as rivers, allowing more flexible site selection.

Interior layouts shifted as steam and later electricity enabled centralised power transmission, reducing the need for scattered small machines.

This encouraged multi-floor factories with more efficient workflow management and closer supervision of labour.

Strong patent protections incentivised inventors by ensuring they could profit from inventions, thereby encouraging continuous experimentation.

Businesses accumulated large patent portfolios, granting them competitive advantages and sometimes enabling them to dominate specific markets.

Patent disputes, though common, often stimulated further innovation as companies sought alternative methods or improved processes to avoid infringement.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which technological innovation contributed to increased industrial output in the United States between 1865 and 1898.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Marks are awarded as follows:

1 mark for identifying a valid technological innovation or development (e.g., the Bessemer process, mechanisation, improved machinery).

1 mark for explaining how this innovation increased industrial output (e.g., faster production, lower costs, standardisation).

1 mark for providing specific supporting detail linked to the period (e.g., expansion of steel production enabling railroad and building growth).

Maximum: 3 marks.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Evaluate the relative importance of natural resource availability compared with technological innovation in driving industrial growth in the United States between 1865 and 1898. Support your answer with specific historical evidence.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Marks are awarded as follows:

1–2 marks for describing technological innovation and/or natural resource availability in general terms.

1–2 marks for explaining how each factor contributed to industrial growth (e.g., abundant coal and iron reducing production costs; new technologies increasing mechanisation and efficiency).

1–2 marks for evaluative judgement that compares their relative importance (e.g., arguing that resource availability enabled new technologies, or that innovations maximised the value of existing resources).

For full marks, the answer must include specific historical evidence drawn from the period 1865–1898.

Maximum: 6 marks.