AP Syllabus focus:

‘Facing increased violence, discrimination, and scientific theories of race, African American reformers continued to fight for political and social equality.’

African Americans in the post-Reconstruction South confronted entrenched racism, escalating violence, and exclusionary laws, yet reformers mobilized politically, socially, and intellectually to assert rights and demand equality.

Heightened Violence and the Struggle for Safety

As Reconstruction-era protections collapsed, southern Black communities endured widespread violence aimed at suppressing mobility, political influence, and economic advancement. Lynching, used as a tool of racial terror, became a central method of enforcing white supremacy.

Lynching: The extrajudicial killing of individuals, often by mobs, intended to intimidate and control targeted communities.

Despite federal attempts, such as repeated but unsuccessful anti-lynching bills, national lawmakers failed to intervene meaningfully, reinforcing the vulnerability of African Americans. Local law enforcement often ignored or enabled mob violence, and courts rarely prosecuted perpetrators. This climate shaped the urgency and strategies of Black activism.

Activist Responses to Racial Violence

Prominent reformers developed strategies to expose brutality and mobilize public opinion.

Ida B. Wells conducted investigative journalism documenting lynching’s causes and patterns.

Portrait of Ida B. Wells, an African American journalist and reformer who exposed lynching through investigative reporting. Her work linked racial violence to political repression and energized anti-lynching activism during the Gilded Age. Source.

Activists promoted boycotts and encouraged migration away from dangerous regions.

Community organizations offered mutual protection, legal aid, and moral support.

These efforts underscored the essential link between safety and the pursuit of broader civil rights.

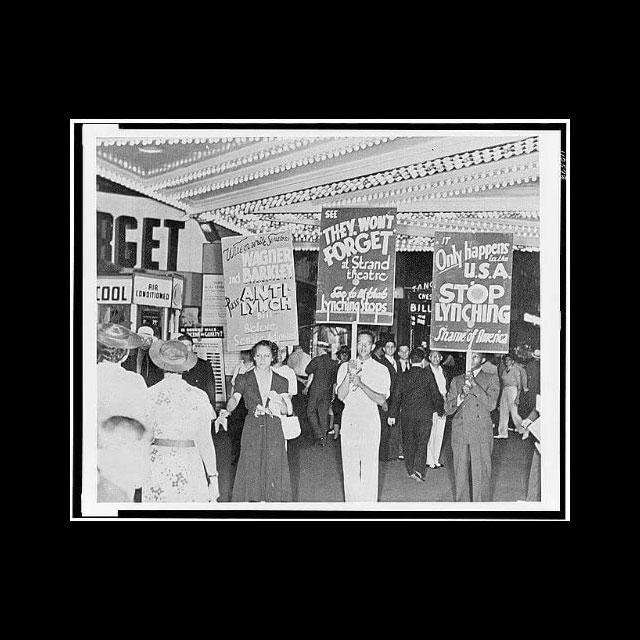

Black demonstrators march with signs calling for a federal anti-lynching bill, reflecting the national effort to expose racial violence and demand legal protection. Although later than 1898, the image illustrates the continuity of anti-lynching activism rooted in the Gilded Age. Source.

Legalized Discrimination and the Fight for Political Rights

By the 1880s and 1890s, southern states constructed a comprehensive system of Jim Crow laws that curtailed African American civic participation. Voting restrictions such as literacy tests, poll taxes, and grandfather clauses silenced Black political influence.

Jim Crow laws: State and local statutes enforcing racial segregation and inequality in public facilities and civic life.

A normal sentence appears here to maintain required spacing.

In addition to political disenfranchisement, segregation permeated schools, transportation, and public accommodations. African American reformers argued that such barriers violated both citizenship rights and the promises of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. Legal challenges emerged, yet courts often upheld discriminatory statutes, strengthening activists’ resolve to pursue alternative strategies.

Institutional and Grassroots Responses

African American leaders formed networks of organizations aimed at resisting legal discrimination.

Churches served as centers of political and social mobilization.

Newspapers and pamphlets spread information, criticism, and calls to action.

Education initiatives prepared a new generation of reform-minded citizens.

These institutions sustained community cohesion under systemic repression.

The Challenge of Racist Theories

The late nineteenth century witnessed the rise of scientific racism, which misused evolutionary theory and pseudoscience to justify inequality. These ideas influenced public policy, academic circles, and legal decisions, reinforcing discriminatory structures.

Scientific racism: The false application of scientific methods to claim inherent racial hierarchies, often used to legitimize discrimination.

A sentence must follow to avoid consecutive definition blocks.

Such theories shaped national debates over segregation, citizenship, and opportunity. Reformers countered these narratives by emphasizing Black intellectual achievement, cultural contributions, and the capacity for progress within equitable environments.

Rebutting Racist Ideology

African American thinkers, writers, and educators challenged racism through scholarship and activism.

Publications advocated historical accuracy and celebrated Black accomplishment.

Schools and colleges founded by African American leaders demonstrated the value of access to education.

Public lectures and debates addressed misconceptions about race and capability.

These intellectual efforts sought to reframe national perceptions and weaken ideological foundations of discrimination.

Diverse Strategies for Political and Social Equality

The struggle for equality took multiple forms as leaders articulated different paths toward advancement. Booker T. Washington, for example, promoted vocational training and gradual economic progress, arguing that stability and skill-building would foster long-term respect and opportunity. W. E. B. Du Bois, by contrast, insisted on immediate civil rights and academic education for the Talented Tenth, contending that political agitation and intellectual leadership were essential for achieving equality.

Talented Tenth: The concept that a leadership class of educated African Americans should lead efforts for racial uplift and civil rights.

Activists also worked collaboratively across local, regional, and national levels. Women played a particularly significant role; club movements, church groups, and reform associations addressed issues of education, labor, public health, and moral uplift. These networks built solidarity and maintained pressure for change despite hostile circumstances.

Community Building and Collective Action

African American activism emphasized both self-help and systemic reform.

Mutual aid societies supported economic stability and social welfare.

Legal defense organizations confronted unjust laws and court decisions.

Public campaigns encouraged literacy, home ownership, and political awareness.

Collectively, these initiatives demonstrated resilience, adaptability, and a commitment to securing rights in a period marked by oppressive policies.

Expanding the National Conversation

As violence, discrimination, and racist theories intensified, African American reformers broadened their appeals to national audiences. They petitioned Congress, wrote for national newspapers, joined interracial reform movements, and engaged supporters in the North and West. Their activism exposed contradictions between American ideals and racial realities, compelling the nation to confront issues that would shape the coming century.

FAQ

Activists relied on alternative networks to bypass hostile officials. Black newspapers, church communities, and travelling investigators collected testimonies directly from witnesses and families.

Researchers also compared multiple reports, cross-checking dates, names, and locations to expose inaccuracies in official statements.

This process helped activists build national databases of racial violence long before federal institutions attempted similar documentation.

Motivations varied considerably:

Some were religious reformers who viewed mob violence as morally unacceptable regardless of race.

Others feared the erosion of legal order that lynching represented.

A small number supported the movement after personal encounters with African American activists who framed the crisis as a national rather than a sectional problem.

These alliances were fragile but occasionally useful for expanding public awareness.

Black women’s clubs created extensive local networks that supported political education, literacy programmes, and community safety.

They organised fundraising efforts, published newsletters, and trained younger women in leadership roles.

These clubs also coordinated with national organisations, giving local concerns a broader platform and helping to define a gendered dimension of civil rights activism.

Churches expanded their role beyond spiritual life. Ministers addressed scientific racism directly in sermons and public lectures, challenging claims of racial inferiority.

Congregations built schools and reading rooms to promote intellectual development.

Church-based debate societies encouraged critical discussion, helping communities articulate informed responses to discriminatory ideologies.

Although the North was less formally segregated, activists still encountered:

Hostile audiences who accepted scientific racism as mainstream thought

Venue restrictions imposed by local authorities or private organisations

Press commentary that dismissed or mocked their arguments

Despite these barriers, public lectures remained essential for reaching national audiences and countering racial pseudoscience.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Identify one challenge African American activists faced when campaigning against racial violence in the late nineteenth century, and explain how this challenge shaped their strategies for seeking equality.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark:

Identifies a relevant challenge (e.g., widespread lynching, lack of federal intervention, complicity of local law enforcement, judicial inaction, or the influence of scientific racism).

1 additional mark (up to 2):

Provides a basic explanation of how the challenge affected activist strategies (e.g., turning to investigative journalism, forming community organisations, building national awareness, or promoting migration for safety).

1 additional mark (up to 3):

Offers a clearer or more developed explanation showing a direct causal link between the challenge and specific activist responses (e.g., Ida B. Wells documenting lynching to counter false narratives; activists using print media to circumvent unresponsive courts; reliance on mutual aid societies due to exclusion from political institutions).

(4–6 marks)

Using your knowledge of the period 1865–1898, evaluate the extent to which African American reformers were successful in countering discrimination and racist theories during the Gilded Age. In your answer, consider both their methods and the limitations they encountered.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

1–2 marks:

Demonstrates general knowledge of African American activism during 1865–1898 (e.g., anti-lynching journalism, grassroots organising, political advocacy).

May describe one or more methods used by reformers.

3–4 marks:

Analyses the extent of success, showing awareness of both achievements (e.g., raising national awareness, building community institutions, challenging racist ideology) and limitations (e.g., entrenched Jim Crow laws, continued violence, judicial resistance).

Provides historically accurate examples.

5–6 marks:

Offers a balanced and well-argued evaluation linking actions to their outcomes.

Integrates specific evidence such as the work of Ida B. Wells, Black newspapers, church-led activism, or educational institutions.

Shows clear understanding of the broader context, including political disenfranchisement and the persistence of scientific racism.

Demonstrates insight into the long-term influence of these reform efforts despite short-term obstacles.