AP Syllabus focus:

‘Economic growth expanded opportunity, but recurring instability pushed Americans to reform society and the economic system.’

Between 1890 and 1945, rapid economic expansion created new possibilities for Americans, yet recurring crises exposed systemic weaknesses that spurred reform movements and reshaped national policy.

Expanding Industrial Growth and Opportunity

Economic transformation in this period stemmed from the continued rise of industrial capitalism, which concentrated production in large corporations and generated unprecedented levels of output.

Drivers of Economic Expansion

Growth of heavy industry, including steel, oil, and chemicals.

Innovations in mass production, marketing, and corporate management.

Expansion of national transportation and communication networks.

Increased availability of capital through banks and investment firms.

As industrialization accelerated, many Americans gained access to higher wages, new consumer goods, and improved standards of living.

Corporate Consolidation and Instability

Corporate consolidation produced trusts and monopolies, which could dominate prices and markets. Their rise contributed to recurring periods of boom and bust. When economists and reformers used the term business cycle, they referred to the repeated pattern of economic expansion and contraction.

Business Cycle: The recurring pattern of economic growth, crisis, recession, and recovery that characterized industrial economies.

These cycles exposed the vulnerability of workers, farmers, and small businesses to forces beyond their control.

Instability and Social Strain

Economic instability revealed structural weaknesses in American capitalism. Financial panics—such as those in 1893 and 1907—caused factory closures, unemployment spikes, and banking collapses.

Labor Conflict and Urban Challenges

Industrialization intensified workplace conflict as laborers struggled with low wages, long hours, and unsafe conditions. Some key dynamics included:

Rising militancy of unions like the American Federation of Labor (AFL).

Formation of more radical alternatives, including the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

Growth of strikes in mining, railroads, and manufacturing.

Urbanization brought additional pressures: overcrowded tenements, inadequate sanitation, and graft in municipal governments. Public frustration with political machines like Tammany Hall encouraged calls for reform.

Reform Movements Emerge

Instability pushed Americans to advocate for social and political reform. The Progressive Era—roughly 1900 to 1917—developed from these concerns and sought to remedy the problems generated by unregulated industrial growth.

Progressive Goals and Strategies

Progressives believed that government should play a stronger role in regulating economic life. Their strategies included:

Promoting antitrust legislation to curb corporate power.

Increasing government oversight of banking, food safety, and transportation.

Supporting democratic reforms such as the initiative, referendum, and direct election of senators.

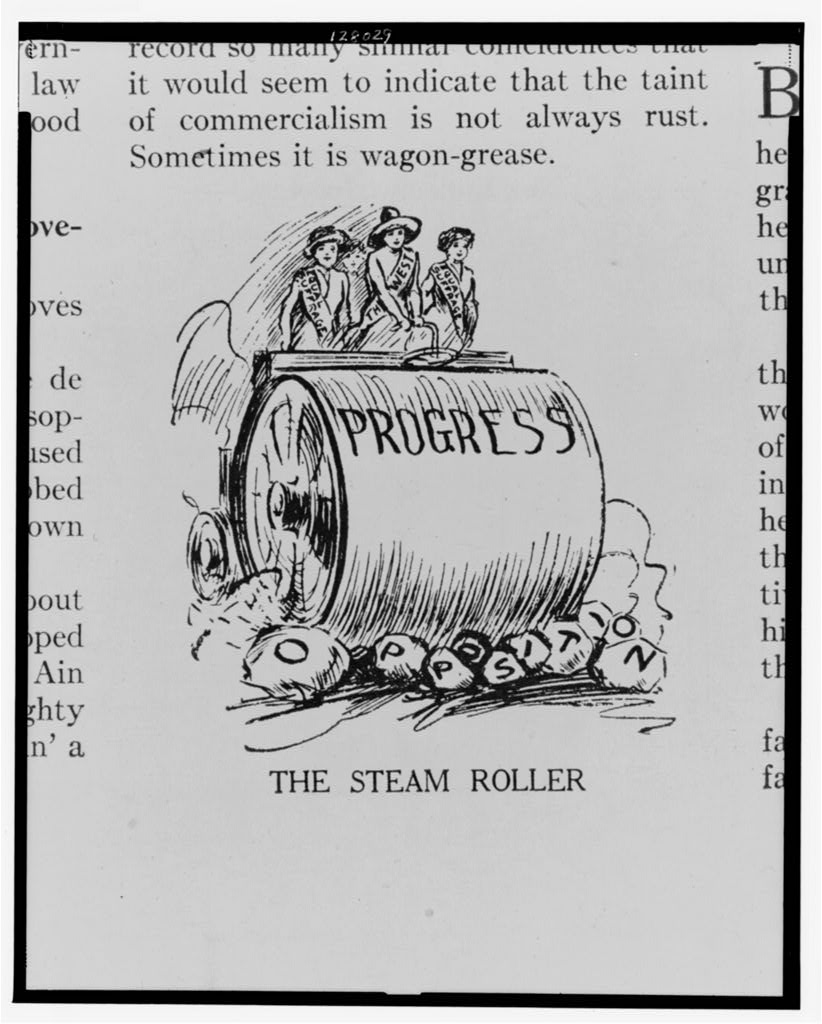

This Progressive-era cartoon depicts women riding a steamroller labeled “Progress,” symbolizing the expanding political influence of reformers. It highlights efforts to broaden democratic participation through movements such as women’s suffrage. The image extends slightly beyond the notes by focusing specifically on suffrage activism. Source.

Many Progressives also supported social welfare initiatives aimed at reducing poverty and protecting children. Middle-class women played critical roles in settlement houses and public health campaigns.

Government Institutions and Regulation

The federal government expanded its regulatory authority through agencies and legislation:

The Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) strengthened oversight of railroad rates.

The Pure Food and Drug Act and Meat Inspection Act regulated consumer goods.

Early labor protections, though limited, recognized the rights of workers and addressed unsafe conditions.

The Great Depression and New Reform Directions

The collapse of 1929 produced the most severe economic crisis in U.S. history.

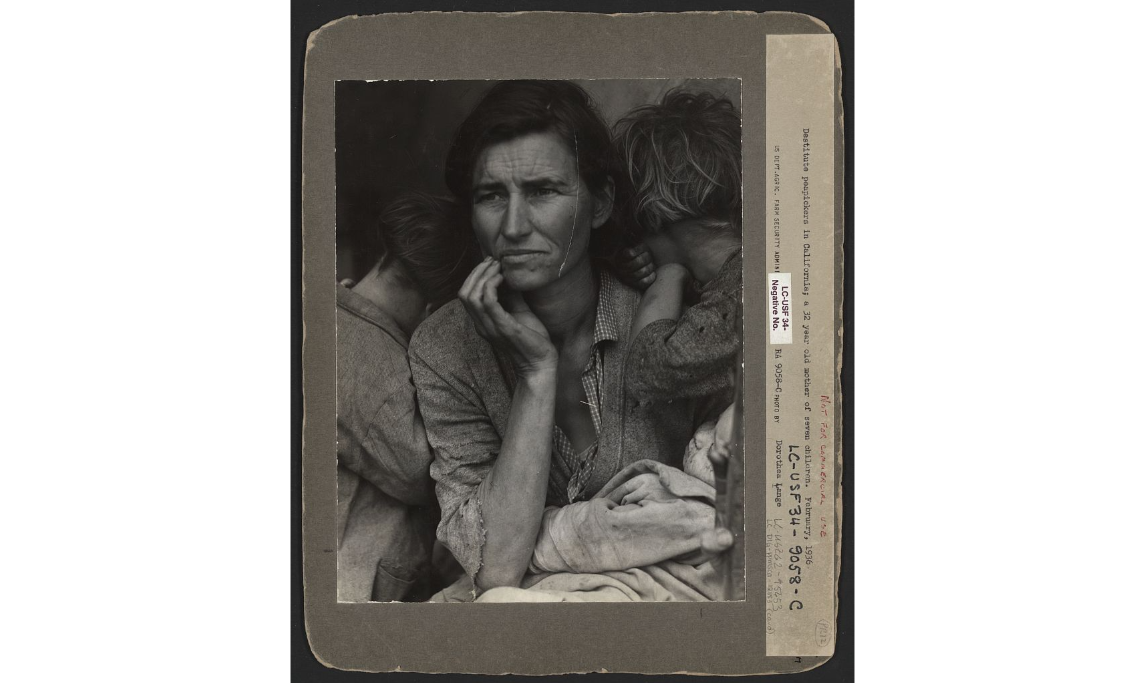

A mother sits with her children pressed against her shoulders, their strained expressions revealing the hardships of Depression-era poverty. The image demonstrates the human toll of mass unemployment and economic instability. It includes additional context about migrant farmworkers, a group not named directly in the notes. Source.

High unemployment and widespread poverty further demonstrated the fragility of industrial capitalism.

Instability Becomes National Emergency

Bank failures, deflation, and collapsing demand forced Americans to reconsider the role of government. While earlier reforms attempted to regulate within existing systems, the scale of the Great Depression required more expansive action.

The New Deal and the Redefinition of Liberalism

Franklin Roosevelt’s administration introduced the New Deal, an array of programs aimed at relief, recovery, and reform. It transformed federal authority in several ways:

Relief programs addressed immediate hardship for unemployed workers and struggling families.

Recovery initiatives attempted to stimulate industry and agriculture.

Long-term reforms created banking regulations, social insurance, and labor protections.

Modern American Liberalism: A political philosophy that supports active government involvement to promote economic security, regulate markets, and address social inequality.

These reforms reshaped expectations of government responsibility and created institutions with lasting impact.

Balancing Growth and Reform by 1945

By the end of World War II, the United States had become the world’s most powerful industrial nation. Yet throughout this fifty-five-year span, Americans continually negotiated the tension between economic opportunity and systemic instability.

Key Patterns Across the Era

Rapid industrial growth expanded jobs, wealth, and consumerism.

Repeated crises demonstrated weaknesses in financial markets and corporate power.

Reform movements—from Progressivism to the New Deal—sought to stabilize and humanize the economic system.

Government played an increasingly central role in managing economic risks and protecting citizens.

Together, these developments defined an era in which Americans confronted the costs of industrialization and reimagined the relationship between the state, the economy, and society.

FAQ

Technological advances such as electrification, mechanised production, and improved communications fuelled rapid industrial expansion by lowering costs and increasing productivity.

However, these same innovations intensified instability by enabling firms to scale quickly, outcompete smaller businesses, and worsen overproduction during downturns. Sudden shifts in technology also displaced workers, deepening unemployment in periods of recession.

Financial systems grew more complex, with banks, trusts, and investment houses extending credit aggressively to fuel industrial expansion.

This created vulnerability because:

• Speculative investment inflated asset values.

• Bank failures could cascade due to limited regulation.

• Credit contraction during downturns worsened unemployment and business collapse.

Such structural weaknesses helped turn normal recessions into severe national crises.

Rising wages and mass-produced goods encouraged many Americans to associate economic success with consumption rather than traditional measures such as landownership.

Advertising and department stores reinforced the idea that prosperity was accessible through modern living standards. At the same time, disparities in access to consumer goods revealed inequalities that reformers used to argue for social and economic regulation.

Farmers, industrial workers, and urban poor families faced the harshest consequences of instability because their incomes were tied directly to fluctuating commodity prices or factory employment.

These groups supported reform because:

• Falling crop prices and debt crises hurt rural households.

• Unemployment and wage cuts hit industrial workers hardest.

• Limited welfare support left families vulnerable during downturns.

Their lived experiences made them central voices in demanding economic intervention.

Even prior to the 1930s, many Americans gradually shifted from viewing government as a minimal regulatory presence to seeing it as an institution responsible for managing economic fairness.

This shift stemmed from:

• Public outrage over corruption and monopolistic practices.

• Expanding acceptance of expert-led agencies.

• Growing belief that modern industrial conditions required oversight.

By the time the Great Depression struck, expectations for government involvement were already evolving, laying groundwork for more extensive reform.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which economic growth between 1890 and 1945 expanded opportunities for Americans.

Question 1

1 mark:

• Identifies a valid opportunity created by economic growth (e.g., increased factory employment, rise of consumer goods, higher wages).

2 marks:

• Provides a clear explanation of how industrial or economic changes created this opportunity.

3 marks:

• Offers specific detail or an example that strengthens the explanation (e.g., mass production improved affordability; urban job growth attracted migrants; expansion of large corporations created managerial roles).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse the extent to which recurring economic instability between 1890 and 1945 contributed to demands for government reform.

Question 2

4 marks:

• Describes at least one episode of economic instability (e.g., Panic of 1893, Panic of 1907, Great Depression) and links it to calls for reform.

• Shows basic understanding of why instability encouraged public pressure for regulation or intervention.

5 marks:

• Develops the argument with clear explanation, such as showing how instability exposed weaknesses in capitalism or intensified labour unrest, prompting Progressive reforms or New Deal policies.

• Uses at least one specific reform or historical development (e.g., antitrust laws, regulatory agencies, welfare state measures).

6 marks:

• Provides a well-reasoned analysis addressing the extent of the impact, noting differing periods or types of reform (Progressivism vs. New Deal).

• Demonstrates nuance (e.g., not all groups agreed on reforms; instability was one cause among others such as urbanisation or social activism).

• Integrates specific evidence to support a balanced judgement.