AP Syllabus focus:

‘New media and migration reshaped American culture, while global conflicts pushed the United States toward greater international power and debate over its role abroad.’

New media technologies, internal and global migration, and accelerating international conflicts transformed American cultural life and reshaped debates about national identity and global responsibility during Period 7.

Mass Culture and the Rise of New Media

Expansion of a National Consumer Culture

The early twentieth century witnessed a dramatic expansion of mass culture, a term referring to widely shared cultural products and experiences accessible to large audiences. Innovations in printing, advertising, and communications allowed ideas, entertainment, and consumer goods to circulate across the nation with unprecedented speed.

Mass-circulation newspapers and national magazines standardized news consumption.

Advertising agencies created recognizable brands that unified consumer expectations across regions.

Department stores and mail-order catalogues connected rural and urban Americans to the same products and trends.

Radio and Film as Cultural Unifiers

The growth of radio broadcasting created real-time national experiences. Entertainment programs, comedy shows, and presidential “fireside chats” reached millions, helping cultivate a shared cultural vocabulary.

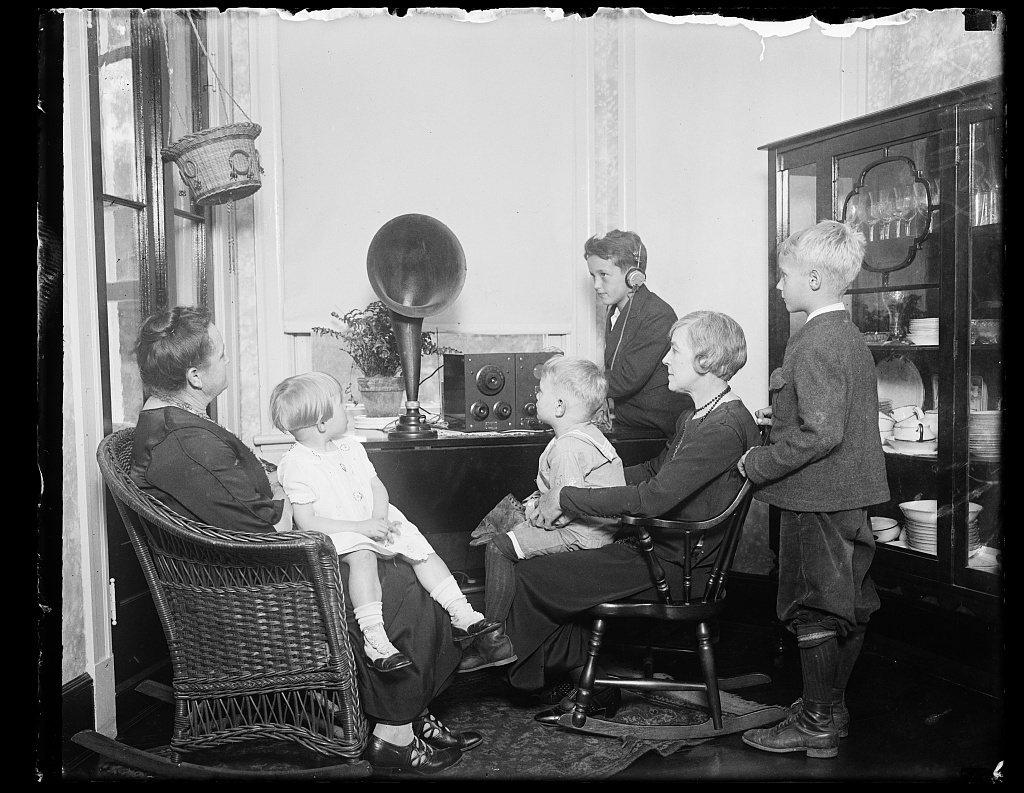

A family gathers around a radio in the 1920s, turning a new technology into a shared daily ritual. Scenes like this helped spread the same news, music, and entertainment to households across the United States at the same time. The image underscores how radio knit together a national mass culture while still operating in intimate domestic spaces. Source.

Similarly, Hollywood cinema became a dominant force, producing narratives that both reflected and shaped American values.

Mass culture: Cultural products and experiences widely shared across large populations, often spread through modern communication technologies.

These shared media forms heightened awareness of regional and ethnic differences while simultaneously promoting a homogenized national identity.

Migration, Identity, and Cultural Change

Internal Migration and Urban Transformation

Americans from diverse backgrounds moved in large numbers during this era, reshaping cultural life. Urbanization accelerated as rural individuals sought industrial employment in cities. The resulting demographic shifts intensified cultural exchange and sometimes cultural conflict.

Rural migrants adapted to new urban norms and expectations.

Growing cities became centers of artistic innovation and political activism.

Exposure to different cultural groups spurred both tolerance and tension.

Immigration and Cultural Diversity

Although immigration slowed during World War I and faced restriction in the 1920s, communities of international immigrants persisted as vital contributors to urban culture.

This statistical map shows the proportion of foreign-born residents across the United States in 1900, with darker shading indicating areas of higher immigrant concentration. It highlights how immigration clustered in specific regions and cities, especially in the Northeast, Midwest, and parts of the West. The map predates World War I but helps explain why early twentieth-century urban centers contained dense immigrant communities that influenced culture, politics, and labor. Source.

Ethnic neighborhoods sustained traditional customs while also blending into mass American culture through schools, workplaces, and media consumption.

The Great Migration and Cultural Expression

The Great Migration of African Americans to northern and western cities reshaped American culture through new literary, musical, and artistic movements.

This 1926 map depicts industrial zones, parks, transportation lines, and ethnic or language groups, revealing how different communities clustered in specific Chicago neighborhoods. It illustrates the spatial effects of migration, including the movement of African Americans during the Great Migration, alongside patterns of immigration. The map includes extra detail on industrial and transit structures, providing additional context for understanding the urban environment of the period. Source.

Great Migration: The large-scale relocation of African Americans from the rural South to northern and western cities to escape segregation and seek economic opportunity.

This movement enriched American cultural life while also exposing persistent discrimination and racial tension in new urban environments.

America’s Expanding Global Role

Global Conflicts and Shifting Diplomatic Responsibilities

As the United States became increasingly involved in global affairs—particularly during World War I and World War II—domestic debates intensified over the nation’s proper role abroad. Policymakers confronted questions of isolationism, intervention, and the promotion of democratic ideals.

Global wars required mobilization of industrial and military resources.

The U.S. economy and culture became intertwined with international developments.

Public opinion oscillated between avoiding entangling alliances and asserting global leadership.

Cultural Reflections of International Power

America’s emerging international presence influenced popular culture. Films celebrated national heroism, newsreels depicted military events, and radio broadcasts framed global conflicts in moral terms. These media forms encouraged Americans to see the United States as a central actor in shaping world order.

Migration and America’s International Identity

Movements of people into and out of the United States highlighted the nation’s global connections. Wartime labor demand brought Mexican and Caribbean workers to American industries and farms, contributing to cultural exchange and adding new voices to debates over citizenship and national belonging. Simultaneously, restrictive immigration policies reflected ongoing anxiety about cultural change and international threats.

Debates Over America’s Place in the World

Tension Between Isolationism and Internationalism

Many Americans resisted foreign entanglements, especially after World War I’s human and financial costs. However, global crises challenged the viability of strict isolationism. New media coverage of international events made foreign developments feel immediate and unavoidable.

Isolationists emphasized national sovereignty and the dangers of overseas commitments.

Internationalists argued that global leadership was necessary to protect democracy and stability.

Cultural narratives in film, radio, and literature amplified both perspectives.

Redefining National Identity in a Global Era

As mass culture and migration transformed society, Americans reconsidered what it meant to be part of a diverse nation with expanding international influence. Cultural production—music, literature, journalism, and film—became a battleground for defining American values in a world increasingly shaped by mobility, communication, and conflict.

FAQ

Advertising agencies learned to craft messages that appealed to broad national audiences rather than local tastes. This encouraged consumers across regions to aspire to similar lifestyles and purchase the same products.

Campaigns often used celebrity endorsements and emotional appeals, helping standardise cultural expectations about modern living. As a result, advertising became a powerful force in defining national identity and shaping daily habits.

Neighbourhood cinemas offered accessible entertainment for diverse communities and acted as informal social hubs. They exposed audiences to national and international newsreels, Hollywood storytelling, and shared cultural references.

Because theatres were inexpensive, they brought varied social classes together. This helped reinforce a sense of collective cultural participation long before broadcasting became widespread.

Large influxes of migrants—both international and domestic—shifted voting blocs and reshaped party strategies.

Political machines often courted immigrant communities by providing services such as job placement or language assistance. Meanwhile, the arrival of African Americans in northern cities challenged long-standing racial hierarchies and forced local leaders to reconsider policies related to housing, schooling, and policing.

Mass media made foreign conflicts and diplomatic crises feel immediate by delivering visual and auditory information directly into homes.

Radio broadcasts framed events using moral or ideological language.

Cinema newsreels provided dramatic imagery of war fronts and international politics.

Newspapers reported rapidly on global developments, connecting domestic opinion to world affairs.

These media collectively encouraged Americans to see themselves as participants in a larger international sphere.

Immigrant groups often established ethnic enclaves that preserved language, religion, and traditions, creating culturally distinct neighbourhoods within cities.

African American migrants, facing segregated housing markets, typically clustered in designated districts. Their cultural contributions—particularly in music, literature, and activism—spread more visibly into mainstream culture, which sometimes sparked racial tension but also fostered broader artistic innovation.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which new media technologies contributed to the development of a shared national culture in the United States between 1890 and 1945.

Question 1

Award up to 3 marks:

1 mark for identifying a relevant new media technology (e.g., radio, cinema, mass-circulation newspapers).

1 mark for explaining how this technology reached broad audiences or standardised cultural experiences.

1 mark for clearly linking this development to the creation of a shared national culture (e.g., simultaneous broadcasts, shared entertainment, nationwide advertising).

Full marks require a clear and accurate explanation that connects cause and effect.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Assess the extent to which migration reshaped American cultural and political debates about national identity during the period 1890 to 1945.

Question 2

Award up to 6 marks:

1 mark for identifying at least one significant form of migration (e.g., internal rural-to-urban migration, immigration, the Great Migration).

1 mark for describing how this migration altered cultural life in cities or communities.

1 mark for explaining how migration contributed to new cultural expressions or social transformations (e.g., Harlem Renaissance, diversification of urban culture).

1 mark for identifying relevant political debates or tensions (e.g., nativism, immigration restriction, debates over racial integration).

1 mark for linking cultural change to broader national debates about identity, values, or America’s role in the world.

1 mark for providing a balanced assessment that addresses the extent of the impact, showing nuance or qualification.

Full marks require accurate historical detail, clear explanation, and a well-supported evaluative judgement.