AP Syllabus focus:

‘Radical, union, and populist movements pushed Roosevelt toward broader changes to the American economic system.’

During the New Deal, growing pressure from radicals, labor unions, and populist reformers compelled the Roosevelt administration to expand federal intervention, reshape economic policy, and confront inequalities exposed by the Great Depression.

Rising Pressures on the Early New Deal

Roosevelt’s early New Deal programs (1933–1934) focused on stabilizing markets, shoring up banks, and providing limited emergency relief. While these initiatives slowed economic decline, many activists argued that the measures did not go far enough. As unemployment remained high and corporate influence appeared unchecked, diverse political forces mobilized outside mainstream politics. Their criticisms broadened public debate about the appropriate scope of federal power and demanded new approaches to economic justice.

Radical Challenges from the Left

Radical figures and movements voiced deep dissatisfaction with the limited reach of early reforms and pushed for more transformative policies.

Radicalism: Political movements advocating fundamental changes to economic, social, or political systems rather than incremental reforms.

Key radical critics included:

Huey Long, whose Share Our Wealth program proposed capping personal fortunes, guaranteeing family incomes, and expanding social benefits.

Black-and-white photograph of Senator Huey P. Long speaking from behind his desk in 1935. The image illustrates the charismatic, populist leadership that challenged Roosevelt from the left and demanded more aggressive redistribution of wealth. It contains no additional details beyond what is relevant to the study notes. Source.

Francis Townsend, who called for a generous federal pension program to stimulate consumption by providing monthly payments to older Americans.

Father Charles Coughlin, whose National Union for Social Justice criticized banking practices and demanded inflationary monetary policies.

Although these figures held divergent beliefs, they shared a conviction that the New Deal lacked the ambition necessary to address structural inequalities. Their mass followings alarmed the Roosevelt administration, encouraging new federal initiatives aimed at redistributing income and addressing poverty more directly.

A central issue raised by radicals concerned the concentration of wealth and power. Critics argued that corporate consolidation and limited worker protections perpetuated hardship. Roosevelt understood that responding to these critiques was essential not only for economic recovery but also for preserving political stability amid the global rise of authoritarian ideologies.

Expanding Voice and Influence of Labor Unions

Labor activism surged during the 1930s as workers demanded improved wages, safer working conditions, and greater bargaining power. Unions became a significant force pushing the New Deal leftward.

Collective bargaining: The process in which workers negotiate with employers as a group to secure improved working conditions, wages, and rights.

The economic crisis had weakened workers’ leverage, but New Deal legislation—especially the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA)—initially encouraged union organizing. Even after the Supreme Court struck down the NIRA, union membership continued to climb, driven by frustration with corporate resistance and by growing solidarity through organizations such as:

The American Federation of Labor (AFL), which traditionally organized skilled workers.

The Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), founded in 1935 to organize industrial and unskilled workers, especially in steel, auto, and mining sectors.

Sit-down strikes, mass picketing, and high-profile conflicts—such as the 1936–1937 Flint sit-down strike against General Motors—demonstrated new forms of labor militancy.

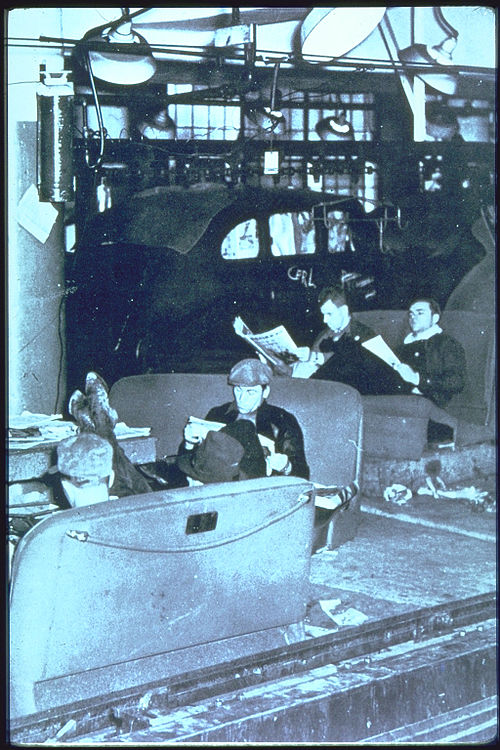

Black-and-white photograph of auto workers participating in the Flint sit-down strike at a General Motors Fisher Body plant in 1937. The image shows workers seated among factory machinery, demonstrating a new tactic of occupying workplaces to force negotiations. No extra details beyond the strike environment are included. Source.

Union pressure influenced Roosevelt to embrace more systematic federal protections. The pivotal Wagner Act (1935), also known as the National Labor Relations Act, guaranteed workers the right to organize and required employers to bargain collectively. This legislation dramatically shifted the balance of power in industrial relations and reflected the administration’s increasing responsiveness to organized labor’s demands.

Populist Reformers and the Push for Broader Economic Change

Populist movements, drawing support from rural communities, small farmers, and advocates of cooperative economics, also pressed the administration to address long-standing inequalities. Their critiques focused particularly on agricultural prices, debt burdens, and corporate domination of markets.

Populist pressure influenced policies such as:

Strengthened farm supports that went beyond early Agricultural Adjustment Act measures.

Regulatory programs aimed at curbing monopolistic practices in transportation, utilities, and agricultural processing.

Expanded rural infrastructure, including electrification projects that improved living standards and connected rural Americans to national markets.

While populists varied in ideology, they shared a belief that federal intervention should safeguard ordinary citizens from unchecked economic power. Their persistent lobbying and widespread voter support expanded the political space for bolder federal initiatives.

Transformation of the New Deal Under External Pressures

By 1935, Roosevelt launched the Second New Deal, a more ambitious phase shaped directly by radical, union, and populist demands. Key measures included:

The Social Security Act, which created old-age pensions, unemployment insurance, and aid to vulnerable populations.

The Works Progress Administration (WPA), providing millions of jobs through public works and cultural programs.

Stronger financial and corporate regulation, including taxes targeting large incomes and corporations.

These programs addressed concerns that the early New Deal had not adequately redistributed economic power or created lasting safeguards against future crises.

Long-Term Significance of Pressure from Reform Movements

The activism of radicals, unions, and populists broadened the national conversation about economic justice, legitimized stronger federal intervention, and helped solidify the modern welfare state. Their pressure ensured that the New Deal evolved beyond emergency response into a more comprehensive redefinition of American liberalism and the responsibilities of the federal government.

FAQ

Roosevelt recognised that the mass appeal of figures such as Huey Long and Francis Townsend signalled widespread frustration with limited early New Deal reforms.

As a result, he shifted towards more assertive rhetoric against concentrated wealth and emphasised the achievements of the Second New Deal to demonstrate that his administration, not the radicals, offered the most practical route to economic security.

Their popularity also motivated Roosevelt to consolidate a broader coalition by reassuring moderate voters while addressing the concerns of those drawn to radical solutions.

Conservative Democrats feared that growing union militancy, especially sit-down strikes, threatened business stability in their regions.

Many represented Southern states that relied on low-wage labour and resisted federal interference in workplace relations.

They also feared that empowered industrial unions would strengthen the Northern wing of the Democratic Party, potentially shifting national power away from Southern political interests.

Radical plans such as Share Our Wealth and Townsend pensions questioned long-standing assumptions that economic outcomes were primarily the result of individual effort.

They encouraged Americans to consider structural causes of poverty, shifting attention to inequalities in wealth distribution.

By proposing government guarantees of income or security, these movements widened public debate about whether the state should ensure a minimum standard of living.

Unions framed workplace issues as national concerns rather than isolated disputes.

They publicised unsafe factory conditions, wage exploitation and anti-union violence, helping Americans view workers’ struggles as linked to broader economic injustice.

Public support grew through:

Highly visible strikes.

Coordinated messaging by the CIO.

Media coverage portraying workers as ordinary citizens seeking fair treatment.

Populist movements expanded rural expectations that the federal government should play an active role in stabilising agricultural markets and protecting small producers.

They criticised corporate control over pricing, transportation and credit, highlighting how rural hardship was tied to structural power imbalances.

This helped persuade many farmers that long-term federal intervention, not just emergency aid, was necessary to secure economic fairness and community stability.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Identify one way in which radical or populist critics influenced the development of the New Deal in the mid-1930s.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark for a simple identification of influence (e.g., “They pressured Roosevelt to adopt more extensive welfare measures”).

2 marks for identifying a specific movement or figure and linking it to a New Deal change (e.g., “Huey Long’s Share Our Wealth plan encouraged Roosevelt to support more redistributive policies”).

3 marks for clearly explaining a specific influence on policy development, such as the creation or expansion of programmes (e.g., “Townsend Plan pressure contributed to the administration adopting old-age pensions in the Social Security Act”).

(4–6 marks)

Explain how labour unions and radical reform movements shaped federal economic policy during the Second New Deal. In your answer, consider both the pressures exerted by these groups and the legislative responses introduced by the Roosevelt administration.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

4 marks for a general explanation of how labour unions and radical movements influenced federal policy, showing basic understanding of their demands and the government’s responses.

5 marks for a more detailed explanation including named groups or individuals (e.g., CIO, AFL, Huey Long, Townsend), plus at least one concrete legislative outcome (e.g., the Wagner Act, Social Security Act).

6 marks for a well-developed answer that integrates:

Clear description of pressures from unions (such as sit-down strikes and growth in union membership).

Clear description of pressures from radicals or populists (e.g., Long’s redistribution proposals or Townsend’s pension campaign).

Specific legislative or policy responses showing how these pressures shaped the Second New Deal (e.g., pro-union rights in the Wagner Act, expanded welfare in Social Security, greater federal intervention).