AP Syllabus focus:

‘After World War I, the United States often pursued unilateral policies using investment, peace treaties, and limited interventions to promote an international order while still maintaining isolationism.’

After World War I, Americans sought stability without deep foreign entanglement. Policymakers balanced isolationist sentiment with selective engagement, using economic tools and diplomacy to shape the international order.

The Postwar International Context

Following World War I, the United States emerged economically strengthened yet socially wary of global commitments. Many Americans believed European conflicts were rooted in age-old rivalries and desired to avoid repeat entanglement. At the same time, American policymakers recognized that global economic instability and political upheaval could threaten national interests. This tension produced a foreign policy characterized by unilateralism, defined as a strategy in which a nation acts independently rather than through binding alliances, while still employing selective international engagement to shape outcomes abroad.

Unilateralism: A foreign policy approach in which a nation acts independently without forming binding alliances or committing to collective security agreements.

American leaders used this approach to maintain maximum freedom of action. Yet they also understood that promoting stability—especially economic stability—benefited U.S. prosperity. This duality framed many U.S. actions in the 1920s and 1930s.

Economic Tools as Instruments of Influence

Investment and International Stabilization

The U.S. relied heavily on private investment and financial diplomacy to shape world affairs. Rather than sending troops or joining military alliances, policymakers encouraged banks and corporations to invest abroad, believing this would stabilize regions while expanding American markets.

Key practices included:

Extending loans to European nations struggling with postwar reconstruction.

Influencing currency stabilization, especially in Germany and Central Europe.

Promoting American economic models, such as mass production and market integration, to strengthen global capitalism.

These strategies aligned with isolationist impulses by avoiding military entanglement yet allowed the United States to exert considerable economic influence.

The Dawes Plan and the Web of Economic Agreements

Although designed by private experts, the Dawes Plan (1924) reflected the federal government’s encouragement of financial solutions to political conflicts.

It restructured German reparations and involved substantial American loans. The United States committed no military or treaty obligations, but its economic presence was central to European recovery.

Similarly, Washington supported tariff diplomacy, even as domestic protectionism—most notably the Fordney-McCumber Tariff (1922)—complicated international trade. Policymakers attempted to reconcile domestic economic nationalism with international stabilization, illustrating the persistent contradictions of unilateralism.

Peace Treaties and Alternative Diplomacy

Arms Limitation Efforts

The United States hosted the Washington Naval Conference (1921–22), where nations negotiated limits on naval armaments.

Delegates convene at the Washington Naval Conference to negotiate naval-arms limitations intended to stabilize power relations in the Pacific. The photograph demonstrates how the United States facilitated multilateral diplomacy while remaining outside the League of Nations. The image focuses solely on the conference environment without adding extra substantive detail. Source.

Although the resulting treaties aimed to maintain peace in the Pacific, they reflected a uniquely American approach: shaping international norms without joining overarching security arrangements.

Pursuit of Peace Without Alliances

U.S. policymakers also backed agreements that attempted to limit war itself. The Kellogg-Briand Pact (1928), which renounced war as a tool of national policy, embodied the idealistic dimension of interwar diplomacy. Yet it required no enforcement mechanism and imposed no binding mutual defense obligations. This symbolic commitment fit the broader pattern of selective engagement without collective security.

Collective Security: A system in which multiple nations agree to defend one another against aggression through binding commitments.

By avoiding collective security, the United States upheld isolationist principles while still participating in high-level diplomacy that shaped international expectations.

Limited Interventions in the Western Hemisphere

Continuity and Change in Latin American Policy

Despite isolationist rhetoric, the United States intervened selectively in the Western Hemisphere, asserting regional influence while avoiding long-term military commitments. Interventions often arose from concerns over political instability or perceived threats to American investments.

Notable patterns included:

Financial supervision, such as influencing national budgets in the Dominican Republic and Haiti.

Support for friendly governments to preserve economic and strategic interests.

Periodic military landings, though increasingly unpopular at home.

Policymakers justified this regional activism under the logic that hemispheric stability protected national security without entangling the nation in European conflicts.

The Good Neighbor Shift

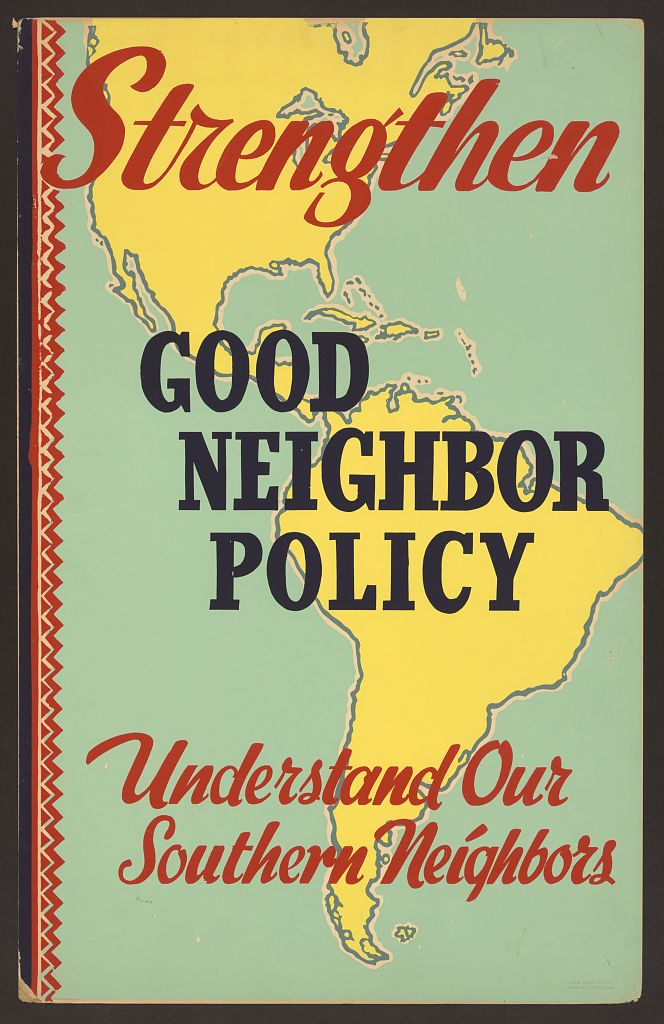

By the early 1930s, a shift occurred with the Good Neighbor Policy, which reduced direct military intervention while emphasizing cooperation and non-interference.

WPA poster promoting the Good Neighbor Policy, highlighting the shared geography and cooperative aims of U.S.–Latin American relations. It visually represents the hemispheric focus and public-diplomacy dimension of the policy. The poster reflects broader Pan-American messaging beyond the specific examples in the notes. Source.

Although more restrained, the policy maintained U.S. regional influence through diplomacy and economic leverage.

Balancing Isolationism and Global Influence

Domestic Pressures

Isolationism gained strength after World War I, fueled by disillusionment with wartime propaganda and the belief that economic interests—not national security—had drawn the United States into conflict. Congress responded with neutrality legislation and resistance to joining international institutions such as the League of Nations.

Policymakers’ Selective Engagement

Even as Congress and the public embraced isolationism, executive officials recognized that complete disengagement was unrealistic for a rising economic power. As a result, U.S. foreign policy blended:

Unilateral action, avoiding binding alliances.

Selective engagement, using economic, diplomatic, and occasional military tools.

Promotion of an international order that reflected American interests and values without formally committing the nation to collective defense.

This approach shaped American diplomacy throughout the interwar period and set the stage for evolving strategies on the eve of World War II.

FAQ

American leaders saw international economic stability as essential to sustaining domestic prosperity. A strong global economy protected U.S. export markets and reduced the risk of foreign defaults on wartime loans.

At the same time, political pressure to avoid foreign entanglements meant economic tools were preferred over alliances. As a result, the government encouraged private loans and financial restructuring abroad rather than committing public funds or military force.

Hosting conferences allowed the U.S. to influence international rules—particularly naval limits and peace commitments—without accepting obligations.

This strategy let American policymakers shape outcomes while preserving freedom of action. It also enhanced the nation’s international prestige, demonstrating leadership without requiring participation in permanent organisations like the League of Nations.

Officials feared that political instability or foreign intervention in the Western Hemisphere could threaten U.S. security and commercial interests.

Key motives included:

Protecting American investments in railways, mines, and agriculture

Limiting European economic or political influence

Ensuring stable governments that could repay debts and honour treaties

Widespread disillusionment with World War I created suspicion toward foreign commitments. Many Americans believed the nation had been misled into war by economic interests and therefore demanded strict limits on international involvement.

As a result, policymakers had to frame engagement in ways acceptable to voters, emphasising peace, economic benefit, and the avoidance of military obligations. This shaped the tone and structure of treaties and financial arrangements.

Financial diplomacy offered a low-risk method to stabilise Europe while avoiding domestic backlash against foreign commitments. It relied on banks, investors, and economists rather than troops or alliances.

This approach also reflected a belief that economic reconstruction would naturally promote political stability. By supporting currency reform, debt restructuring, and credit flows, the U.S. could guide European recovery without appearing to dictate political outcomes.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify one way in which the United States pursued unilateralism in the 1920s while still engaging selectively in international affairs.

Mark scheme (3 marks total)

1 mark for identifying a valid example of unilateralism (e.g., avoiding membership in the League of Nations; refusing binding alliances).

1 mark for identifying a form of selective engagement (e.g., participation in the Washington Naval Conference; involvement in the Kellogg–Briand Pact; financial diplomacy such as the Dawes Plan).

1 mark for a brief explanation linking both elements (e.g., the U.S. shaped global affairs through diplomacy or loans whilst keeping its independence in foreign policy).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Explain how economic and diplomatic policies in the interwar period reflect the United States’ attempt to balance isolationist sentiment with selective international engagement.

Mark scheme (6 marks total)

Up to 2 marks for describing relevant economic policies (e.g., loans to Europe, the Dawes Plan, use of private investment to stabilise Germany and promote U.S. interests).

Up to 2 marks for describing relevant diplomatic efforts (e.g., Washington Naval Conference, Kellogg–Briand Pact, hosting peace negotiations without joining collective security arrangements).

Up to 2 marks for explaining how these actions balanced domestic isolationism with international involvement (e.g., the U.S. avoided binding commitments yet used economic and diplomatic tools to shape the global order).