AP Syllabus focus:

‘In the 1930s, most Americans opposed military action against Nazi Germany and Japan until the attack on Pearl Harbor drew the United States into World War II.’

American foreign policy in the 1930s reflected deep fears of another global conflict, prompting neutrality measures that shaped U.S. responses to aggression abroad and framed the path toward Pearl Harbor.

Neutrality in the 1930s

American reactions to growing global instability were shaped by the profound legacy of World War I, which many citizens believed had resulted from misguided intervention and economic entanglements. A cultural and political commitment to isolationism (a belief that the United States should avoid involvement in foreign conflicts) dominated public opinion and congressional action. These attitudes informed legislation designed to prevent the nation from being drawn into another major war.

The Roots of American Isolationism

Widespread disillusionment with World War I led Americans to question whether the conflict had served national interests. Congressional investigations intensified these doubts.

Isolationism: A foreign policy stance advocating minimal political or military involvement in international affairs to avoid entangling the nation in foreign conflicts.

In the early 1930s, the Great Depression further reduced enthusiasm for foreign policy activism. With economic survival taking precedence, many believed the United States should conserve resources and avoid risky international commitments.

Key influences on isolationist sentiment included:

Nye Committee hearings (1934–1936), which investigated claims that arms manufacturers and bankers had pushed the nation into World War I for profit.

The rise of pacifist movements and widespread resistance to military spending.

The belief that European and Asian conflicts were distant and did not threaten core American interests.

Legislative Neutrality and Its Goals

Congressional action reflected strong public pressure to codify isolationism into law.

Black-and-white photograph of a crowded Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing in 1939, where Henry L. Stimson warned that the Neutrality Act could make the United States more vulnerable to attack. The image illustrates how debates over neutrality unfolded in a formal legislative setting, with senators, officials, and spectators all engaged. It includes additional detail about specific individuals and committee procedures that goes beyond the syllabus but helps contextualize the intensity of the neutrality debates. Source.

The Neutrality Acts of the 1930s were intended to insulate the United States from foreign wars by limiting the actions that had previously pulled the nation toward conflict.

The Neutrality Acts, 1935–1937

These laws evolved over time but shared the goal of preventing economic or military engagement with nations at war. Major provisions included:

A mandatory arms embargo on belligerent nations.

Restrictions on American travel on ships belonging to nations at war.

Prohibitions on loans or credits to belligerents.

A “cash-and-carry” policy (1937) allowing the sale of nonmilitary goods only if buyers paid upfront and transported materials themselves.

Cash-and-carry: A policy permitting nations at war to purchase goods from the United States if they paid in cash and transported the goods independently.

These measures reflected the prevailing assumption that economic ties could drag the nation into war. The laws sought to reduce risk while allowing limited economic exchange.

Rising Global Threats and Challenges to Neutrality

Although Americans preferred neutrality, events abroad made complete disengagement increasingly difficult. Expansionist actions by Japan, Nazi Germany, and Fascist Italy challenged the notion that the United States could remain insulated from world affairs.

Japanese Expansion and American Responses

Japan’s invasion of Manchuria (1931) and later attacks on China intensified concerns in Washington. However, the United States responded mainly with diplomatic protests and mild economic measures, such as the Stimson Doctrine, which refused to recognize territorial acquisitions made by force. Many Americans viewed Asian conflicts as remote, reinforcing the desire to maintain neutrality.

European Aggression and the Limits of Noninvolvement

As Adolf Hitler expanded German territory—occupying the Rhineland, annexing Austria, and demanding the Sudetenland—Americans watched anxiously but remained opposed to intervention. The neutrality framework constrained the Roosevelt administration, which sought flexibility as the threat of global war increased.

Shifting Attitudes at the End of the Decade

By 1939, war in Europe forced reconsideration of strict neutrality. Although public opinion still opposed direct military involvement, Americans increasingly recognized that Allied defeat could endanger U.S. security.

Policy Adjustments Toward Limited Support

Roosevelt gradually pushed for modifications that would aid nations resisting aggression:

The Neutrality Act of 1939 expanded cash-and-carry provisions to include arms sales.

The administration promoted moral condemnation of aggressive states through speeches like the Quarantine Speech (1937), which suggested isolating aggressors to preserve peace.

These steps did not signify full intervention but illustrated a growing recognition that neutrality might be insufficient in a world dominated by militaristic states.

The Road to Pearl Harbor

While most Americans still opposed war with Japan or Germany in 1941, escalating tensions made conflict increasingly likely. Japanese expansion into Southeast Asia threatened U.S. interests, prompting the Roosevelt administration to impose embargoes on oil and other critical materials. Negotiations deteriorated as Japan sought to maintain its empire while the United States demanded withdrawal from conquered territories.

On December 7, 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, abruptly ending isolationist sentiment.

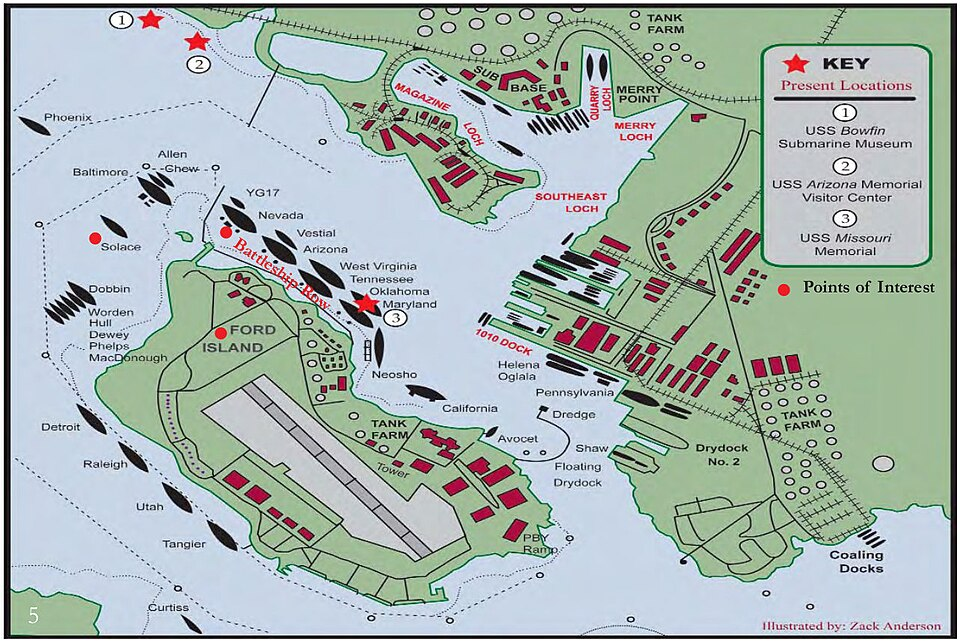

Map of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, showing Ford Island, surrounding channels, and key naval installations targeted in the Japanese attack. The map clarifies the spatial relationship between the harbor’s anchorages and the broader base, illustrating why the strike was so devastating to the U.S. Pacific Fleet. It includes a few present-day facilities that are not directly required by the syllabus but do not interfere with understanding the 1941 layout. Source.

The assault convinced the public that neutrality was no longer viable and brought the United States fully into World War II, aligning with the AP syllabus emphasis on how opposition to military action persisted until the attack itself forced national mobilization.

Aerial photograph taken from a Japanese plane during the torpedo attack on Pearl Harbor, showing Ford Island surrounded by burning and listing U.S. warships. The image highlights the concentrated nature of the attack on Battleship Row and helps explain why the strike so dramatically altered American views on neutrality. The original description also identifies individual ships and technical details that go beyond the syllabus but can enrich student understanding of the attack’s military impact. Source.

FAQ

Polling throughout the decade consistently showed that most Americans opposed entering another European or Asian war, even as they expressed sympathy for victims of aggression.

This influenced Congress to adopt policies reflecting caution, such as avoiding commitments that might draw the nation into conflict. Roosevelt had to adjust his rhetoric and strategies to support preparedness without appearing interventionist.

Public opinion constrained policymakers, slowing major shifts in foreign policy until events made neutrality untenable.

Sanctions were seen as a tool that avoided military engagement while signalling disapproval of aggressive states. Policymakers hoped that limiting access to resources would pressure nations like Japan to moderate expansion.

Key assumptions included:

Economic dependence made aggressors vulnerable.

Sanctions could unify domestic opinion without risking war.

Stronger steps might be possible later if necessary.

These expectations proved overly optimistic, particularly regarding Japan’s response to embargoes on oil and strategic materials.

Improved global communications meant Americans received faster, more vivid accounts of events such as bombings in China or Europe, shaping emotional reactions to foreign crises.

These technologies allowed correspondents to broadcast dramatic depictions of warfare, increasing public awareness without necessarily increasing support for intervention.

This combination fostered a sense of global danger while reinforcing the belief that America should avoid direct involvement.

Critics interpreted the speech as an early step toward intervention, fearing it implied economic or military pressure on aggressor nations.

Reactions stemmed from:

A belief that America should avoid taking sides.

Memories of perceived missteps that led to the First World War.

Fears that economic measures could escalate into conflict.

The backlash highlighted how sensitive the political climate remained and how constrained Roosevelt was in responding to global instability.

Japanese leaders viewed American neutrality as selectively applied, believing the United States favoured China and the European Allies despite formal nonalignment.

When embargoes restricted oil and other materials, Japanese officials interpreted these as hostile acts intended to weaken their strategic position.

They concluded that securing resource-rich territories was essential for national survival, accelerating decisions that ultimately contributed to the Pearl Harbor attack.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain one reason why many Americans supported neutrality during the 1930s.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

• 1 mark for identifying a valid reason (e.g., disillusionment with the First World War, economic hardship during the Great Depression, or fear of foreign entanglements).

• 2 marks for providing a brief explanation of how this reason encouraged support for neutrality.

• 3 marks for a well-developed explanation showing clear understanding of the historical context and linking the reason directly to widespread public or political sentiment.

(4–6 marks)

Analyse how developments in American foreign policy during the 1930s contributed to the eventual breakdown of neutrality and the road to Pearl Harbor.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

• 1–2 marks for identifying relevant developments (e.g., Neutrality Acts, Japanese expansion, European aggression, shifting attitudes by 1939).

• 3–4 marks for explaining how these developments affected American views or policies, demonstrating connections between events and neutrality’s erosion.

• 5–6 marks for a well-structured analysis showing clear cause-and-effect, integrating multiple developments, and explicitly linking these to the ultimate failure of neutrality before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.