AP Syllabus focus:

‘New technologies and manufacturing methods shifted the economy toward consumer goods, improving living standards, increasing mobility, and strengthening communications systems.’

Rapid advances in industrial methods transformed American production, enabling affordable consumer goods, higher living standards, accelerated mobility, and a unified national market shaped by mass manufacturing and technological innovation.

Mass Production and the Transformation of the American Economy

By the 1920s, the United States underwent a profound economic shift driven by mass production, a manufacturing approach that emphasized high output, standardization, and efficiency. These developments allowed businesses to produce unprecedented quantities of goods at lower cost, reshaping consumer expectations and accelerating economic growth. New manufacturing technologies reinforced a broader transformation already underway since the late nineteenth century: the movement toward an urban, industrial consumer society increasingly dominated by large firms.

New Technologies and Industrial Methods

The introduction of electrified machinery, improved machine tools, and standardized components enabled rapid, continuous production. Mass production thrived on uniformity, allowing factories to reduce waste, limit skilled labor requirements, and increase reliability in the manufacturing process. These technologies empowered companies to produce items ranging from household appliances to automobiles on a scale unimaginable in previous decades.

Assembly lines, widely adopted after the 1910s, embodied the system’s emphasis on interchangeable tasks and coordinated workflow.

Workers on a moving assembly line at Ford’s Highland Park plant in 1913 assemble magnetos and flywheels for Model T automobiles. This photograph clearly illustrates the standardized, repetitive tasks that defined Fordism and made large-scale mass production possible. Technical details such as the specific components being assembled extend beyond what students need to memorize, but they help show how industrial work was broken into simple, specialized steps. Source.

Assembly Line: A manufacturing process in which a product moves sequentially through workstations, each performing a specialized task to increase production efficiency.

This system revolutionized industrial labor. Although factory work became more monotonous, wages often rose, and employment expanded across industrial centers as companies sought large labor forces to sustain continuous output.

A crucial consequence of these technological shifts was the rise of consumer goods industries, which produced radios, refrigerators, vacuum cleaners, automobiles, and other products that increasingly defined modern American life. These goods became symbols of comfort, convenience, and social aspiration in an expanding consumer economy.

Fordism and Industrial Standardization

No figure influenced modern industrial production more than Henry Ford, whose methods came to be known as Fordism. Rooted in the principles of efficiency, standardization, and mass consumption, Fordism reshaped both the workplace and the marketplace by linking high productivity to high wages.

Fordism: A system of mass production characterized by standardized goods, the assembly line, and wages high enough for workers to purchase the products they made.

Fordism operated on two interlinked foundations: the technical system of mass production and the social or economic system that relied on broad consumer demand. Ford’s factories produced millions of identical Model T automobiles, demonstrating the economic power of uniform design and interchangeable parts.

Key Features of Fordism

• Standardization of parts that minimized variation and increased mechanical reliability

• Reduction of assembly time through division of labor and specialized tasks

• High wages, most famously the $5-a-day wage introduced in 1914, intended to reduce turnover and transform workers into consumers

• Lower prices, enabling mass purchasing and expanding market size

This system marked a turning point in the relationship between labor and industry. By raising wages and cutting costs, Ford helped create a cycle in which increased production lowered prices, expanding the consumer base and sustaining continued mass manufacturing.

Consumer Goods and Changing Living Standards

The proliferation of inexpensive, widely available consumer goods transformed daily life. Americans increasingly viewed consumption as a measure of personal fulfillment and national progress. Urban households gained access to electrical appliances that reduced domestic labor and increased leisure time. Radios enabled families to access entertainment and news, forging shared cultural experiences across geographic boundaries.

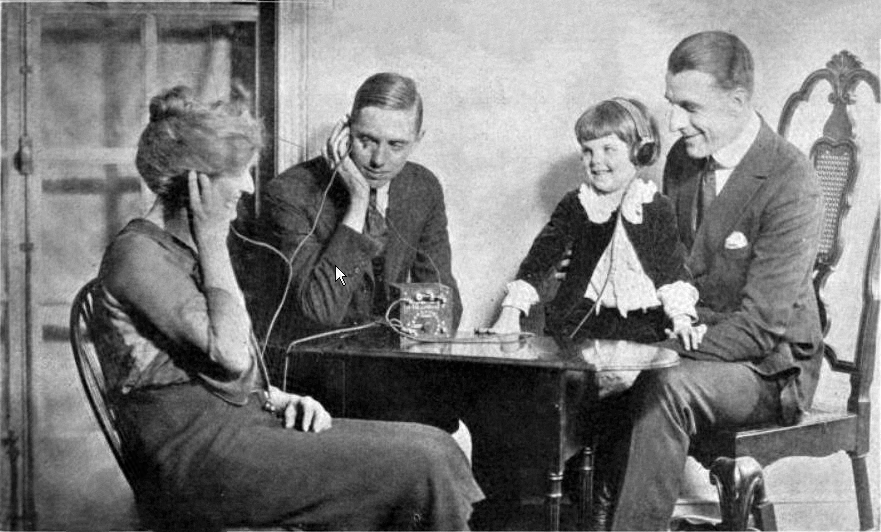

A 1920s American family listens together to a crystal radio, an early home receiver that brought broadcast news and entertainment into living rooms. The image highlights how consumer technologies like radios helped create a shared national culture and strengthened communications networks. Brand-specific details come from the original advertisement and extend slightly beyond what students must know, but effectively illustrate the expansion of consumer goods and communications. Source.

Automobiles produced under Fordist principles revolutionized mobility. Car ownership soared during the 1920s, expanding suburban development, boosting tourism, and generating demand for new infrastructure such as paved roads, service stations, and motels. Mobility reshaped social patterns, granting individuals greater freedom in work, leisure, and residence.

Consumer Culture and Marketing

Simultaneously, advancements in advertising and communications cultivated a national consumer culture. Companies used print media, radio programs, and billboard campaigns to standardize tastes and promote brand loyalty. This widening market reinforced the connection between mass production and mass consumption, encouraging both technological innovation and social change.

Communications Systems and National Integration

Mass production technologies also powered the expansion of communication systems that knit together an increasingly interconnected society. The widespread availability of radios, telephones, and cheaply manufactured electronic components enabled rapid information exchange. These tools strengthened national identity by reducing regional isolation and promoting a shared cultural vocabulary.

Economic Impacts

• Lower production costs expanded markets and increased business profits

• Rising consumer demand stimulated economic growth in related industries (steel, rubber, glass, petroleum)

• Improved communications fostered more integrated national and international trade networks

Together, mass production, consumer goods, and Fordism defined a central transformation of early twentieth-century America. These forces dramatically improved living standards, expanded mobility, and deepened the nation’s commitment to a consumer-driven economic model that shaped both the 1920s and the decades beyond.

FAQ

Ford’s Five-Dollar Day reduced labour turnover dramatically, as workers were less inclined to leave stable, well-paid industrial jobs.

It also pressured competing manufacturers to raise wages, helping establish a new expectation of industrial compensation.

Additionally, Ford imposed standards for employee conduct and home life, reflecting a paternalistic approach that linked wage levels to worker behaviour and productivity.

Standardisation allowed manufacturers to produce identical components that fit reliably into any product unit, reducing waste and simplifying assembly.

It also made maintenance easier for consumers, as replacement parts were uniform.

For businesses, standardisation supported:

• Predictable production schedules

• Lower training requirements for workers

• Easier product scaling as demand increased

Mass production concentrated large factories in urban and industrial centres, drawing thousands of workers into cities for employment opportunities.

The automobile, itself a product of mass production, enabled cities to expand outward. Suburbs grew as commuting became feasible for more workers.

As consumer goods industries expanded, so did retail districts, department stores, and service stations, reshaping the commercial geography of many American cities.

Household appliances such as vacuum cleaners, electric irons, and refrigerators reduced the time required for domestic labour.

Although this did not eliminate women’s domestic responsibilities, it altered expectations of household efficiency and opened more opportunities for women to seek paid employment.

Marketing campaigns also targeted women as decision-makers in consumer purchases, giving them greater visibility in the consumer economy.

Early radios were often simple crystal sets with limited range and inconsistent sound quality, yet they provided real-time access to news, entertainment, and national events.

Radio broadcasts created shared cultural moments across regions, linking rural and urban audiences.

Even with limited fidelity, the ability to hear live music, sporting events, and political speeches fostered a more unified national identity and accelerated the growth of mass culture.

Practice Questions

Explain one way in which Fordism contributed to economic growth in the United States during the 1920s. (1–3 marks)

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

• 1 mark for a simple statement identifying a contribution (e.g., Fordism increased production efficiency).

• 2 marks for a statement with some development (e.g., Fordism reduced production costs, allowing goods to be sold more cheaply).

• 3 marks for a fully explained answer linking Fordism to wider economic effects (e.g., high wages and low prices expanded consumer demand, stimulating broader economic growth).

Using your knowledge of early twentieth-century industrial developments, assess the extent to which mass production transformed American society between 1900 and 1930. (4–6 marks)

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

• 4 marks for a general explanation of mass production with at least one accurate societal impact (e.g., rise in consumer culture, growth of automobile ownership).

• 5 marks for a more detailed answer that discusses multiple impacts and shows clear understanding of social, economic, or cultural change.

• 6 marks for a well-argued assessment that addresses both the extent of transformation and contextual limitations (e.g., not all Americans benefitted equally), demonstrating a balanced analysis and strong supporting evidence.