AP Syllabus focus:

‘Oil crises and U.S. involvement in the Middle East pushed leaders to attempt a national energy policy shaped by military and economic concerns.’

Post-1970 energy crises exposed U.S. vulnerability to foreign oil supplies, prompting policymakers to confront Middle Eastern instability, reexamine national security priorities, and build long-term strategies for energy independence.

The Global Energy Context and U.S. Vulnerability

After decades of inexpensive petroleum, the United States entered the 1970s increasingly dependent on foreign energy, much of it from politically volatile Middle Eastern states. This dependence left the nation exposed when geopolitical shifts disrupted the global oil supply, revealing how deeply economic stability, industrial output, and national security were tied to international energy markets.

The Middle East and Strategic Importance

The Middle East’s vast oil reserves made it central to global energy flows and Cold War strategy. U.S. leaders pursued alliances with key producers to ensure reliable access and to counter Soviet influence in the region. These partnerships intertwined U.S. foreign policy with regional conflicts, heightening the geopolitical stakes of oil security.

The 1973 Oil Crisis and Its Origins

The first major disruption, the 1973 oil embargo, was triggered by the Yom Kippur War, during which the United States supported Israel against Arab states. In response, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) imposed an embargo on nations aligned with Israel.

OAPEC: A coalition of Arab petroleum-exporting states that used oil supply restrictions as a diplomatic and economic tool.

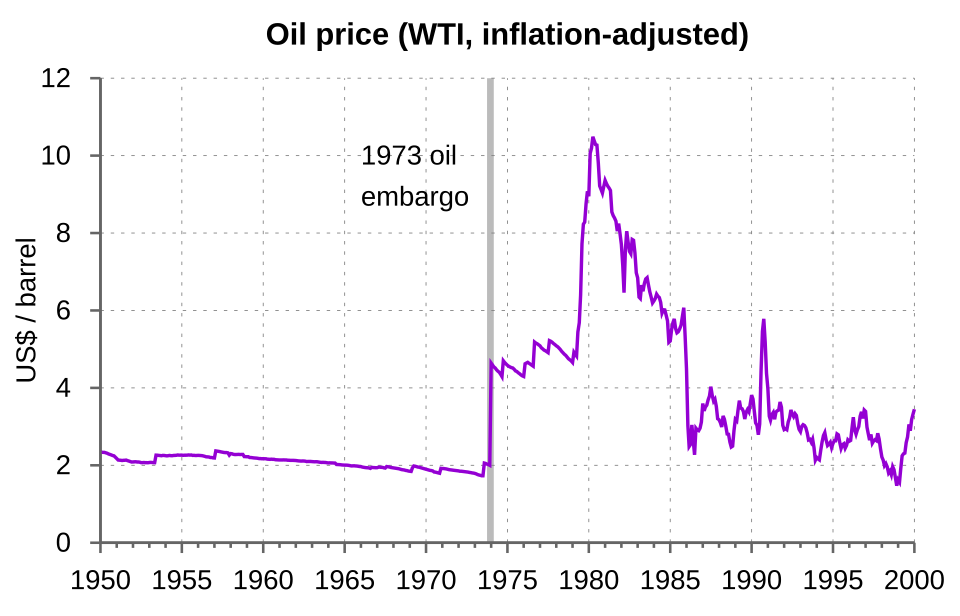

The embargo reduced exports and production, causing shortages and soaring prices. It demonstrated for the first time that energy could be wielded as a strategic weapon. Oil shocks in 1973–1974 and 1979 caused global oil prices to spike dramatically, disrupting trade and fueling worldwide inflation.

Line graph of inflation-adjusted West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil prices from 1950 to 2000, with the 1973 oil crisis clearly highlighted. The graph shows how the first oil shock marked a sharp break from the relatively low and stable oil prices of the postwar era. It extends beyond 1980, providing additional context that is not required by the AP U.S. History syllabus but helps students see longer-term price trends. Source.

Domestic Effects in the United States

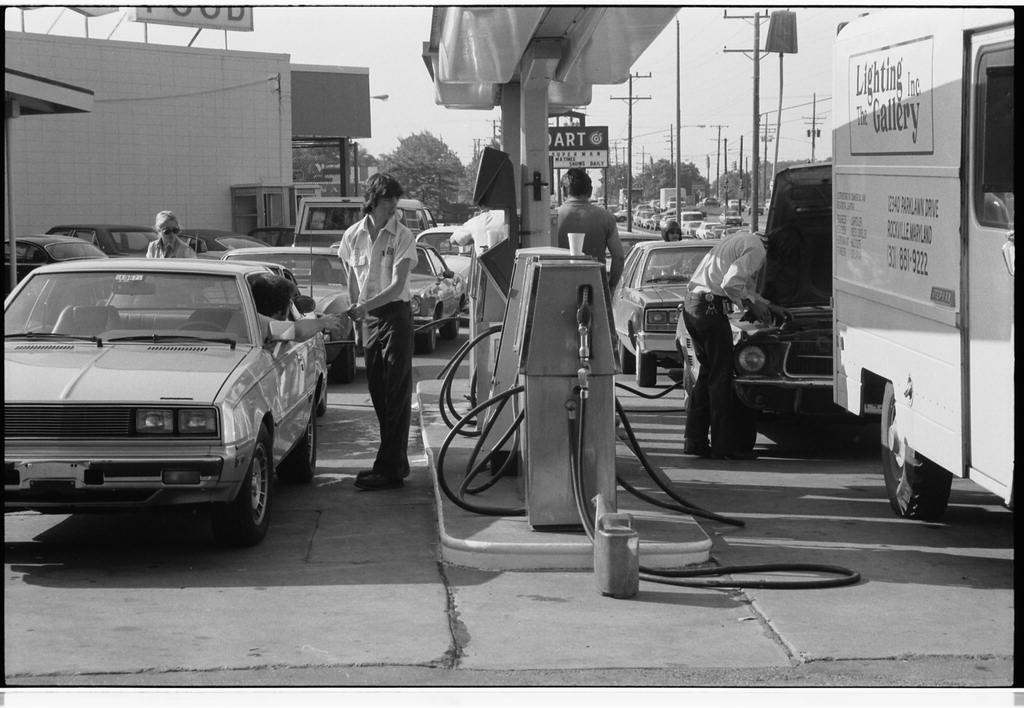

The oil shock created widespread dislocation, including long lines at gas stations, inflationary pressures, and a recession. These disruptions highlighted the fragility of U.S. energy systems and raised fundamental questions about consumption patterns, fuel efficiency, and the balance between domestic and foreign supply. Americans experienced visible shortages through long lines at gas stations, closed pumps, and odd-even rationing systems based on license plates.

Photograph of cars lined up at a U.S. gas station waiting for fuel during a late-1970s gasoline shortage. The scene illustrates how oil supply disruptions and price spikes produced visible, everyday hardships for drivers, including long waits and uncertainty about access to fuel. The photo dates from 1979, slightly after the first 1973–74 embargo, but it accurately represents the recurring gasoline lines associated with the 1970s energy crises as a whole. Source.

The 1979 Energy Crisis and Expanded Geopolitical Tensions

A second major energy crisis erupted in 1979 following the Iranian Revolution, which destabilized one of the world’s major oil exporters. Production declines and market panic led to renewed shortages and price spikes. This crisis deepened public anxiety and intensified calls for a coherent national response.

The Middle East and Cold War Strategy

As instability grew, the United States amplified its military presence in the region. Policymakers framed Middle Eastern oil as essential to preventing Soviet expansion and preserving Western economic strength. These perceptions shaped broader doctrines linking energy security to military intervention capabilities, including rapid-deployment forces designed to respond to regional threats.

U.S. Policy Responses to the Energy Crises

Federal Conservation Initiatives

Policymakers viewed reducing consumption as essential to national resilience. Major conservation and efficiency measures included:

Establishing Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards to improve vehicle efficiency.

Encouraging reduced speed limits to lower fuel consumption.

Promoting insulation and efficient appliances to cut residential energy use.

CAFE Standards: Federal regulations requiring automobile manufacturers to meet average fuel-efficiency targets across their vehicle fleets.

These initiatives reflected a growing recognition that energy security required changes in everyday American life, not simply adjustments in foreign policy.

Expanding Domestic Energy Production

To reduce dependence on imports, the federal government supported exploration in Alaska, the Gulf of Mexico, and other regions. The completion of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System symbolized the push toward tapping new domestic reserves. Policymakers also worked to remove barriers to extraction, encouraging a diversified energy portfolio.

Creation of Strategic Institutions

The crises highlighted the dangers of relying on volatile global markets, prompting structural changes:

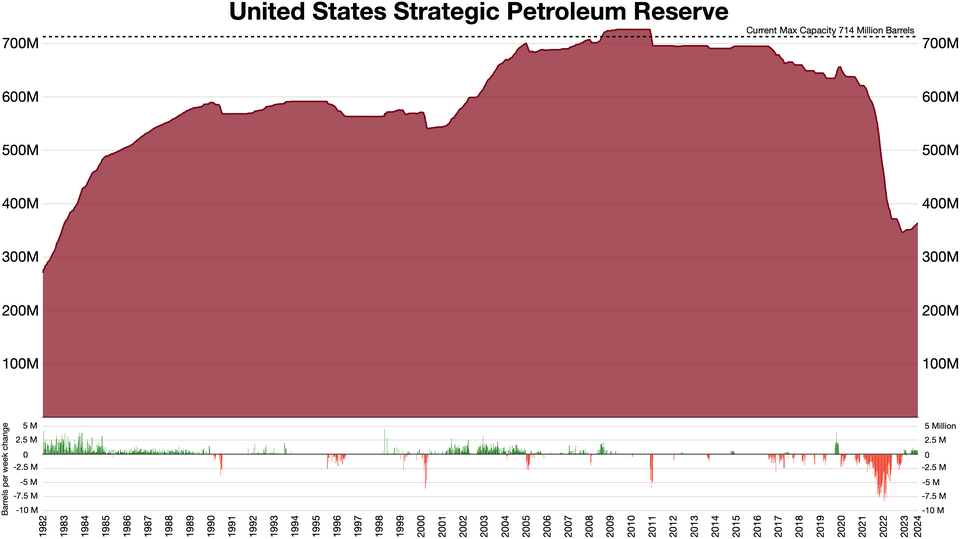

Establishment of the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) to store emergency supplies.

Creation of the Department of Energy (1977) to centralize federal oversight of energy issues.

U.S. participation in the International Energy Agency (IEA) to coordinate responses among oil-importing nations.

Congress also created the Strategic Petroleum Reserve to stockpile crude oil along the Gulf Coast as an emergency buffer against future supply disruptions.

Area chart of the volume of crude oil held in the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve from the late 1970s into the early 21st century. The steadily rising reserve levels in the decades after the 1970s energy crises show how policymakers tried to protect the United States from future sudden supply cutoffs. Much of the data extend beyond 1980, adding later history that goes beyond the APUSH period while still illustrating the long-term impact of decisions made in the 1970s. Source.

The Carter Administration and the Push for a National Energy Policy

President Jimmy Carter placed unprecedented emphasis on energy reform, framing the crisis as “the moral equivalent of war.” His administration sought comprehensive change through legislation encouraging conservation, promoting renewable energy research, and regulating pricing in the oil and natural gas sectors. Carter emphasized that U.S. national security depended on the ability to reduce reliance on unstable foreign suppliers.

The Carter Doctrine

In 1980, Carter articulated a more assertive foreign-policy stance regarding the Persian Gulf. He declared that any outside attempt to control the region would be met with military force. This Carter Doctrine linked energy security directly to potential military intervention, reinforcing the strategic importance of Middle Eastern stability.

Long-Term Implications for U.S. Energy and Foreign Policy

By the end of the 1970s, Americans recognized that energy was deeply intertwined with geopolitical conflict, economic conditions, and federal policy choices. The oil shocks prompted enduring debates over:

The appropriate balance between domestic production and environmental regulation

The role of military power in securing global energy supplies

The feasibility of alternative energy sources

The need for coordinated international energy policies

The crises of the 1970s ultimately reshaped U.S. economic priorities, foreign policy strategies, and public expectations regarding government leadership in managing vital national resources.

FAQ

The embargo encouraged longer-term changes in consumer habits as Americans increasingly evaluated energy efficiency when purchasing cars and household appliances.

It also contributed to growing interest in smaller, foreign-made vehicles, particularly Japanese models, which were perceived as more fuel-efficient than many American cars.

This shift placed competitive pressure on U.S. automakers and signalled changing expectations about reliability, running costs, and environmental awareness among consumers.

The IEA was formed in 1974 to coordinate energy policy among industrialised oil-importing nations in response to OAPEC’s embargo.

Its responsibilities included:

Facilitating emergency oil-sharing arrangements

Collecting data and forecasting supply risks

Encouraging long-term reductions in oil dependence

Through these measures, the IEA created a more unified Western approach to managing energy insecurity, reducing the capacity of oil exporters to isolate individual countries.

U.S. oil fields discovered earlier in the century were maturing, leading to declining output and higher extraction costs just as demand continued to grow.

Environmental concerns also limited drilling in sensitive areas, and new resources such as Alaskan oil faced logistical challenges, including transportation infrastructure and harsh climates.

As a result, increased exploration could not rapidly offset the nation’s heavy dependence on imports from politically volatile regions.

Rising fuel prices and persistent shortages heightened public frustration, contributing to perceptions that the federal government lacked a clear, effective strategy.

President Carter’s televised warnings about energy consumption, though well-intentioned, were sometimes interpreted as pessimistic or moralising, weakening public confidence.

The crisis therefore became both an economic and political turning point, influencing voter attitudes heading into the 1980 election.

Yes. The uncertainty created by volatile oil prices spurred investment in alternative energy research, including solar power, wind technology, and synthetic fuels.

Federal grants and new research institutions encouraged experimentation, even though many technologies remained commercially limited at the time.

The period also saw advances in energy-efficient industrial processes, laying a foundation for later environmental and technological developments in the 1980s and beyond.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify one major consequence of the 1973 oil crisis for the United States and briefly explain how it affected American society or the economy.

Question 1

1 mark for identifying a valid consequence (e.g., fuel shortages, inflation, recession, long petrol queues, higher energy costs).

Up to 2 marks for explaining how this consequence affected society or the economy (e.g., disrupted daily life, reduced consumer confidence, increased production costs, slowed economic growth, encouraged energy conservation).

Maximum 3 marks.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Explain how U.S. involvement in the Middle East shaped federal energy policy in the 1970s. In your answer, consider both the causes and consequences of the oil shocks.

Question 2

1–2 marks for describing U.S. involvement in the Middle East and how geopolitical tensions contributed to the oil shocks (e.g., support for Israel, instability following the Iranian Revolution).

1–2 marks for explaining how these events revealed U.S. dependence on foreign oil and created national vulnerabilities.

1–2 marks for analysing resulting federal energy policies (e.g., creation of the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, conservation measures, CAFE standards, establishment of the Department of Energy, diversification of energy sources).

Maximum 6 marks.