AP Syllabus focus:

‘Evangelical Christian churches grew rapidly, alongside greater political and social activism by religious conservatives.’

The rise of the Religious Right reflected growing concern among conservatives about cultural change, prompting a new political movement that linked evangelical Christianity with organized efforts to reshape national policy.

Growing Evangelical Influence in Late-Twentieth-Century America

The expansion of evangelical Christianity after the 1960s created a large, energized constituency that responded to rapid social change. Many Americans perceived shifting cultural norms—regarding gender roles, sexuality, and family life—as signs of moral decline. Evangelical denominations grew quickly through dynamic preaching, nationwide media outreach, and suburban congregations that fostered strong community identity. This expanding population set the foundation for political mobilization as believers sought to defend what they viewed as traditional American values.

Evangelical Christianity: A Protestant movement emphasizing personal conversion, biblical authority, and active faith, often expressed through revivalism and widespread media outreach.

A significant feature of this growth was the rise of megachurches, which used television, radio, and print networks to build national audiences. Leaders such as Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson gained influence by framing religious concerns in terms of political responsibility. This shift encouraged many evangelicals to reinterpret their civic obligations, believing that defending morality in the public sphere required direct engagement with government policies.

Jerry Falwell stands before a choir and a row of American flags at a 1980 rally, illustrating how the Religious Right fused patriotic imagery with evangelical preaching. Such events framed moral and political issues as national crises requiring Christian activism. The image includes broader symbolism and participants beyond Falwell himself, but all elements reinforce the movement’s public, patriotic style of religious politics. Source.

The Political Awakening of Religious Conservatives

The Religious Right emerged as activists responded to federal decisions they believed threatened traditional values. Several developments acted as catalysts:

Supreme Court rulings that restricted school-sponsored prayer and upheld access to abortion.

Expansion of second-wave feminism and challenges to traditional gender roles.

Growing visibility of the counterculture, which many conservatives associated with moral disorder.

Increased federal regulation of private and religious schools.

These issues created a sense of urgency among conservative Christians who argued that national institutions no longer supported the moral framework essential for stable families and communities.

Religious Right: A coalition of conservative Christians who mobilized in the 1970s to influence politics on issues related to morality, family, and religion in public life.

Although religious activism had earlier precedents, this movement differed in scale and strategy. Evangelicals collaborated with conservative Catholics, Mormons, and secular activists who shared concerns about cultural and political liberalism. Through national networks, they coordinated campaigns that emphasized restoring traditional morality and resisting what they saw as the overreach of federal authority into local and family life.

Institutions and Leaders of the Religious Right

High-profile organizations strengthened political unity among religious conservatives. One of the most influential was the Moral Majority, founded in 1979 by Jerry Falwell. It served as a broad coalition representing millions of conservative Christians and advocating for policies aligned with biblical principles.

Major initiatives included the following:

Supporting pro-family legislation and opposing abortion rights.

Encouraging voters to assess candidates according to moral values rather than party loyalty.

Mobilizing churches to participate in voter registration drives.

Promoting strict anti-communist positions, linking religious concerns to Cold War politics.

The Religious Right also leveraged mass communication. Christian broadcasting networks expanded dramatically during the 1970s, enabling leaders to reach audiences beyond traditional congregations. Television programs blended religious teachings with commentary on political issues, further normalizing evangelical engagement in national debates.

The Religious Right in Electoral Politics

By the late 1970s, activists shifted from issue-based advocacy to coordinated electoral strategy. They recognized that sustained influence required shaping party platforms and candidate selection. Their efforts aligned naturally with the conservative turn occurring within the Republican Party, which increasingly appealed to voters dissatisfied with liberal social policies.

Key political effects included:

A growing alliance between evangelical Protestants and the Republican Party, especially in the South and Sun Belt.

Increased emphasis on social conservatism, including opposition to abortion, pornography, and the Equal Rights Amendment.

Mobilization of first-time voters who saw political participation as an expression of religious duty.

The election of Ronald Reagan in 1980 demonstrated the movement’s rising political power. Although Reagan’s personal religious views differed from many evangelicals, he embraced their priorities and reinforced the idea that the United States had a moral mission. His campaign’s success illustrated how cultural and religious issues could reorganize political coalitions.

“The Religious Right drew especially strong support from white evangelical Protestants in the South and Sun Belt, where conservative churches were numerous and tightly woven into community life.”

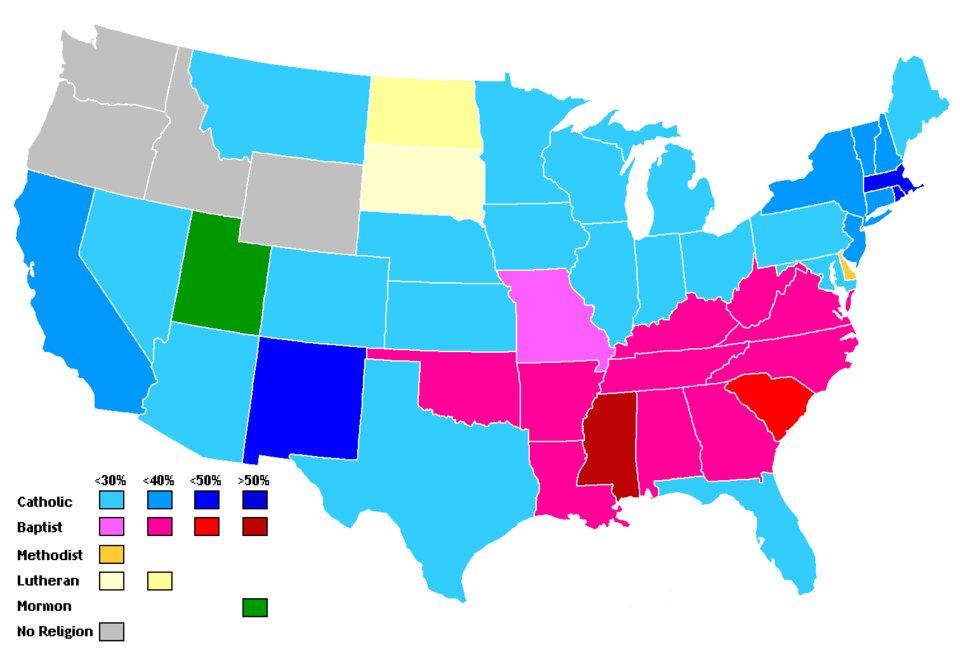

This map shows the largest religious denomination in each U.S. state around 2001, with Baptist majorities concentrated in the South and Sun Belt. These strongholds overlapped closely with regions where the Religious Right gained its greatest political influence. The map includes additional denominations beyond the specific focus of this subtopic. Source.

Cultural Impact and Long-Term Significance

The rise of the Religious Right reshaped national debates over public morality, civil rights, and the proper relationship between religion and government. Activists insisted that the United States was fundamentally a “Christian nation,” arguing that public institutions should reflect biblical values. Critics responded that the movement threatened pluralism and blurred the constitutional separation of church and state.

Beyond policy disputes, the Religious Right influenced broader cultural trends:

Reinforcing traditional family structures and resisting shifts in gender norms.

Challenging secularism in education and promoting creationist perspectives.

Encouraging political candidates to articulate explicit religious identities.

Strengthening networks that tied local church communities to national activism.

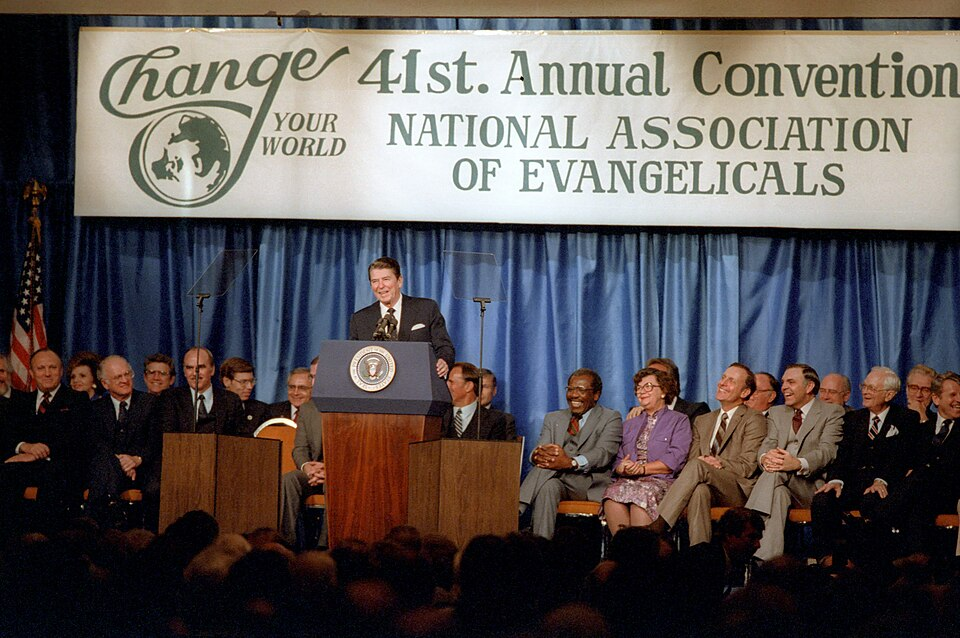

By the early 1980s, Religious Right leaders forged close ties with Ronald Reagan, who courted evangelical voters and echoed their concerns about morality, family, and the Cold War.

President Ronald Reagan addresses the National Association of Evangelicals in 1983, reflecting the growing partnership between conservative evangelical activists and the Republican Party. His speech signaled alignment with Religious Right priorities on morality and Cold War policy. The banner and setting underscore the explicitly religious and political character of the event. Source.

Because evangelical churches continued growing, especially in suburban regions experiencing demographic change, the movement remained a powerful force. Its emphasis on grassroots mobilization, media outreach, and moral framing helped define late-twentieth-century conservatism and continued to influence political discourse into subsequent decades.

FAQ

Televangelism allowed charismatic preachers to reach national audiences, transforming churches from local institutions into mass communication networks. This visibility helped normalise political messaging within religious broadcasts.

Fundraising expanded dramatically as televised ministries solicited donations from viewers across the country. These funds supported political organising, lobbying efforts and voter mobilisation campaigns aligned with Religious Right priorities.

Private Christian schools became symbols of parental control over education, especially as federal regulations increased in the 1970s. Many conservative Christians viewed government oversight as encroaching on religious freedom.

Activists formed networks to defend these institutions, linking educational autonomy with wider political concerns about secularism and moral decline. This activism fed directly into the infrastructure of the Religious Right.

‘Family values’ served as a unifying ideological theme that tied together diverse concerns, from opposition to abortion to resistance against changes in gender roles. It allowed activists to frame political issues as moral threats to the stability of the home.

The emphasis also helped attract supporters who were not deeply religious but shared anxieties about cultural change, broadening the movement’s appeal.

The movement argued that religious expression had been pushed out of public life, advocating policies such as reinstating school prayer or providing public support for religious institutions.

Critics countered that such policies violated constitutional principles by favouring a particular religious viewpoint. This debate reshaped legal and political discourse, making the boundary between church and state a central national issue.

The Republican Party increasingly incorporated social conservatism into its platform, emphasising moral issues alongside economic and foreign policy positions. This shift attracted large numbers of evangelical voters.

Party leaders began forging strategic alliances with religious activists, recognising their organisational strength and electoral influence. Over time, this partnership contributed to a durable ideological realignment within American conservatism.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify one factor that contributed to the emergence of the Religious Right in the 1970s and briefly explain how it encouraged political mobilisation among conservative Christians.

Question 1

1 mark for correctly identifying a relevant factor (e.g., Supreme Court rulings on school prayer, Roe v. Wade, the growth of evangelical churches, cultural shifts such as feminism or the counterculture).

1 mark for explaining how the factor generated concern among conservative Christians (e.g., perceived moral decline or threats to traditional values).

1 additional mark for linking this concern to political mobilisation (e.g., motivated evangelicals to organise, vote, or support conservative candidates).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Explain how the Religious Right influenced American politics by the early 1980s. In your answer, consider both grassroots activism and national electoral politics.

Question 2

1–2 marks for describing the role of grassroots activism (e.g., voter registration drives, church-based organising, use of Christian media networks).

1–2 marks for explaining the movement’s impact on national elections (e.g., alignment with the Republican Party, support for Ronald Reagan in 1980, shaping party platforms).

1–2 marks for analysing the broader political effects (e.g., increased prominence of social conservatism, framing moral issues as national priorities, strengthening links between religion and policymaking).