AP Syllabus focus:

‘To contain expansionist communism and Soviet repression, the United States used multiple measures, including major military engagement in Korea.’

The Korean War tested early Cold War containment as the United States confronted communist expansion in Asia, revealing both the possibilities and limits of American military and diplomatic power.

Origins of Containment in Asia after 1945

Following World War II, U.S. leaders increasingly viewed Asia as a critical front in the global struggle against communism, especially after the division of Korea at the 38th parallel. The northern zone, backed by the Soviet Union, developed into the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), while the southern zone, supported by the United States, became the Republic of Korea (ROK). These developments hardened Cold War tensions and set the stage for conflict. As China’s civil war ended with a communist victory in 1949, U.S. officials interpreted events in Asia as part of a broader pattern of Soviet-directed expansion.

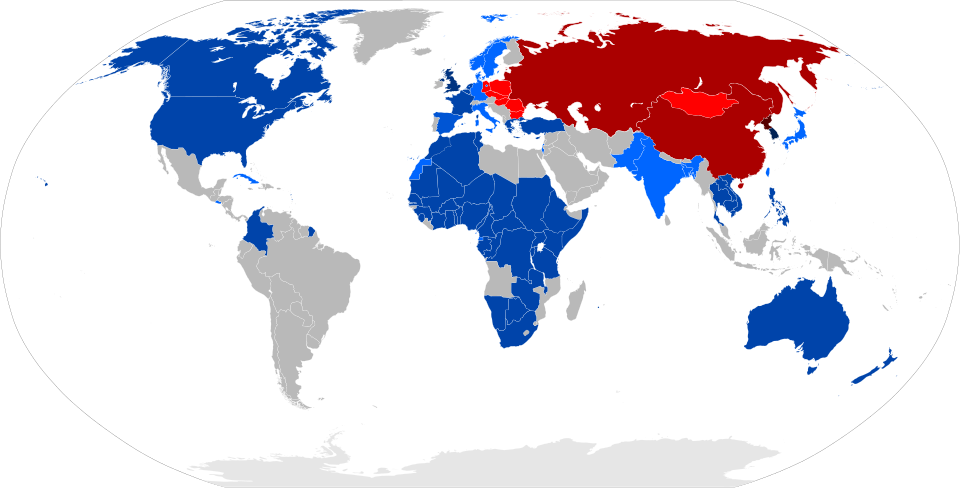

Map showing the Korean Peninsula within the wider Cold War world, with communist and non-communist states distinguished and Korea highlighted. This visualization supports the idea that Korea became a key front in the global struggle between the United States and the Soviet bloc. The map also includes broader world alignments that go beyond the specific events covered in this subtopic. Source.

The Outbreak of War in 1950

War began in June 1950 when North Korean forces invaded South Korea in a rapid offensive aimed at reunifying the peninsula under communist rule. U.S. policymakers, interpreting the attack as a test of American resolve, moved swiftly. President Harry S. Truman framed the conflict as essential to defending the free world, drawing on the broader strategy of containment—the effort to prevent communist expansion wherever it emerged.

Containment: A U.S. Cold War strategy aimed at preventing the expansion of communist influence by political, economic, and military means.

The United States sought international legitimacy by working through the United Nations, which authorized a collective military response. This coordination reflected Truman’s belief that global institutions could bolster American leadership while deterring further aggression.

U.S. Military Intervention and Shifting Strategies

The early phase of the war saw rapid U.S. mobilization as American and UN troops attempted to halt North Korea’s advance. Under the command of General Douglas MacArthur, UN forces launched a counteroffensive at Inchon in September 1950, dramatically reversing North Korean gains and pushing northward.

Landing craft of the first and second waves approach the beaches at Inchon during the UN amphibious landings on September 15, 1950. The photograph illustrates the scale and coordination of MacArthur’s counteroffensive, which turned the tide of the early war. The destroyer USS De Haven appears in the background, a naval detail not emphasized in the AP syllabus. Source.

Confidence soared as policymakers considered the possibility of reunifying Korea under a noncommunist government. However, China’s entry into the war in late 1950 dramatically altered U.S. expectations. Chinese forces drove UN troops southward, revealing the geopolitical risks of expanding containment too aggressively in Asia. The conflict stalemated near the original boundary, complicating U.S. strategy and highlighting the limitations of military solutions to Cold War challenges.

Debates over Escalation and Presidential Authority

The Korean War intensified debates about how far the United States should go to stop communism in Asia. MacArthur advocated expanding the war into China, even suggesting the use of nuclear weapons. Truman rejected these proposals, arguing they risked a wider war with the Soviet Union. Their disagreement culminated in Truman’s dismissal of MacArthur, an important assertion of civilian control over the military.

This controversy revealed deep divisions within American society about the proper use of military power. While many Americans supported a tough stance against communism, others feared that excessive escalation threatened global stability. These debates foreshadowed future disagreements over Cold War conflicts, including Vietnam.

Limited War and the Boundaries of U.S. Power

By 1951, U.S. strategy shifted toward the notion of a limited war, one that aimed to restore stability without provoking direct superpower confrontation. Military operations focused on maintaining positions near the 38th parallel, while diplomats pursued an armistice. The challenge of balancing military action with political constraints illustrated the limits of U.S. power in a nuclear-armed world.

Negotiations dragged on for two years, influenced by disputes over prisoner repatriation and shifting political pressures. Both sides ultimately accepted that a decisive victory was unlikely. The armistice, reached in July 1953, restored the boundary between North and South Korea but did not produce a peace treaty. The peninsula remained divided, symbolizing the enduring tension of Cold War geopolitics.

Consequences for U.S. Foreign Policy in Asia

The Korean War reshaped American foreign policy by demonstrating that containment in Asia required long-term commitments and flexible strategies. Key developments included:

• Massive rearmament under the National Security Council’s NSC-68, which argued for expanded military spending to counter communist threats.

• A stronger U.S. presence in Asia, including alliances such as SEATO (Southeast Asia Treaty Organization).

• Heightened fears of communist expansion, influencing later decisions in Vietnam.

• Recognition that indirect or limited confrontations with communist states were often unavoidable to prevent broader war.

The conflict also bolstered the authority of the executive branch in directing foreign and military policy, an evolution that would spark future constitutional debates. Although the United States prevented the fall of South Korea, the war underscored the constraints of American power, revealing that containment sometimes required accepting stalemate rather than victory.

Legacy of the Korean War in the Cold War Framework

The Korean conflict became a defining early test of Cold War policy. It revealed that military engagement in Asia was complex, costly, and shaped by the interplay of global ideologies. While the United States succeeded in containing communism in South Korea, the stalemate illuminated the challenges of applying containment to regional conflicts influenced by nationalism, decolonization, and superpower rivalry.

FAQ

Korea’s position between China, Japan, and the Soviet Union made it a significant geopolitical buffer in early Cold War strategy. American officials believed that losing Korea to communism would undermine U.S. credibility in Asia and embolden Soviet influence.

The Truman administration also viewed Korea through the wider lens of postwar reconstruction, aiming to stabilise regions vulnerable to ideological conflict. This strategic importance increased after the Chinese Communist Revolution in 1949.

The United Nations’ rapid authorisation of collective military action enabled the United States to frame the conflict as an international defence of sovereignty rather than unilateral intervention.

This multilateral backing strengthened diplomatic support, limited potential criticism from U.S. allies, and established a precedent for future Cold War conflicts where Washington sought broad international endorsement.

The Inchon operation presented difficulties because of extreme tidal variations, narrow channels, and mudflats that limited landing windows.

Key challenges included:

• Coordinating naval bombardment with precise tidal timing

• Navigating unfamiliar and hazardous coastal terrain

• Rapidly securing a port city surrounded by urban infrastructure

Despite these challenges, the assault succeeded largely due to surprise, detailed planning, and concentrated force deployment.

Chinese commanders relied heavily on mobility, numerical strength, and night-time manoeuvres to offset technological disadvantages. Their strategy emphasised infiltration and encirclement rather than conventional front-line pushes.

Unlike North Korean forces, Chinese units exploited rugged terrain and harsh winter conditions, aiming to exhaust UN troops and break supply lines rather than capture territory quickly. This approach contributed to the prolonged stalemate near the 38th parallel.

Talks were delayed by disagreements over prisoner repatriation, as both sides refused forced returns of captured soldiers. Negotiators also struggled with establishing demarcation lines and future security arrangements.

Political pressures in Washington, Pyongyang, Beijing, and Moscow complicated progress, with leaders seeking favourable terms that would signal strength to domestic and international audiences.

The death of Stalin in 1953 ultimately reduced Soviet resistance to compromise, allowing the armistice to proceed.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one reason why the United States viewed the Korean War as an important test of its containment policy in Asia.

Mark Scheme

• 1 mark for identifying a valid reason (e.g., fear of communist expansion after China’s communist revolution).

• 1 mark for explaining how this reason related to containment (e.g., policymakers believed failing to act would signal weakness to the Soviet Union).

• 1 mark for contextual detail showing why Asia appeared strategically vulnerable in 1950.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Evaluate the extent to which the Korean War revealed the limits of U.S. power in the early Cold War.

Mark Scheme

• 1–2 marks for describing relevant features of U.S. strategy or military action (e.g., initial success at Inchon, Chinese intervention forcing retreat).

• 1–2 marks for analysing how these events demonstrated constraints on U.S. power (e.g., risk of escalation with China and the Soviet Union restricted American options).

• 1 mark for incorporating evidence of political limits such as the Truman–MacArthur conflict.

• 1 mark for a linked judgement explaining the overall extent of limitation (e.g., containment was preserved but decisive victory proved unattainable).