AP Syllabus focus:

‘The Cold War shifted between direct and indirect confrontation and periods of coexistence or détente, reshaping U.S. strategy over time.’

The Cold War’s evolving tensions led U.S. policymakers to alternate between confrontational strategies and cautious cooperation, producing shifting diplomatic, military, and ideological approaches that reflected changing global realities.

From Confrontation to Détente

The Shifting Landscape of U.S.–Soviet Relations

The decades after World War II witnessed alternating cycles of escalation and coexistence between the United States and the Soviet Union. These shifts were rooted in ideological rivalry, nuclear competition, and efforts to stabilize a dangerous global environment. Periods of confrontation often emerged from fears of communist expansion, while détente reflected attempts to manage conflict, reduce risk, and create predictable rules of engagement.

Early Cold War Confrontation

Initial U.S.–Soviet tensions hardened into firm policies of containment, the strategy that aimed to limit the spread of communism worldwide.

Containment: A U.S. foreign policy designed to prevent the expansion of communist influence, primarily through diplomatic, economic, and military measures.

Confrontation dominated during events such as the Berlin Crisis, the Korean War, and escalating global competition for influence. These moments reinforced U.S. fears that communist movements—whether Soviet-supported or homegrown—posed a threat to international order.

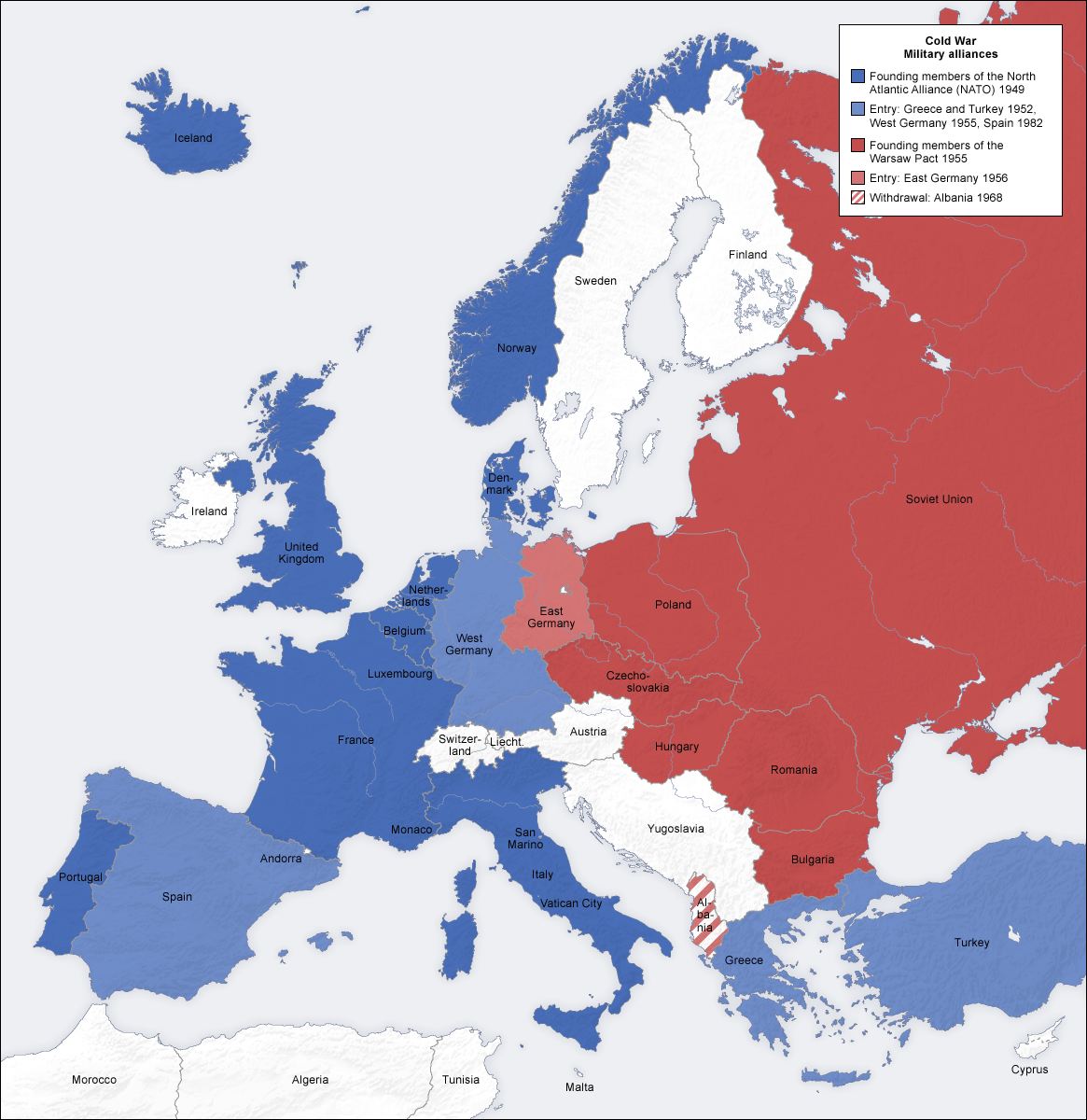

This map illustrates the geopolitical division of Europe into NATO, Warsaw Pact, and neutral states, helping visualize the blocs underlying early Cold War confrontation. It includes minor geographic details beyond syllabus requirements but reinforces the spatial reality of superpower rivalry. Source.

The rise of nuclear weapons transformed confrontation. The strategy of mutually assured destruction (MAD) created a precarious balance in which each side recognized that full-scale war would be catastrophic. This reality pressured both superpowers to explore alternative routes to stability.

The Search for Stability and the Rise of Détente

By the late 1950s and 1960s, both superpowers faced internal and international pressures encouraging more predictable relations.

Key factors that encouraged détente included:

The enormous economic burden of the arms race

Global movements for decolonization that expanded diplomatic complexity

Domestic demands in both nations for reduced tensions

Recognition that nuclear war was unwinnable

As these pressures mounted, leaders began to consider diplomatic strategies that might ease tensions without abandoning fundamental ideological goals.

Diplomatic Efforts and Arms Control

Détente took shape through negotiations, high-level summits, and the development of arms-control measures.

This photograph captures President Richard Nixon and Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev signing the SALT I and ABM agreements in 1972, marking a major step in détente. The image visually demonstrates superpower willingness to limit nuclear arsenals. It includes mention of both treaties, offering slightly more specificity than the syllabus requires but remaining tightly aligned with détente’s diplomatic aims. Source.

One of the earliest breakthroughs was the 1963 Limited Test Ban Treaty, which prohibited atmospheric nuclear testing and demonstrated that cooperation was possible even amid rivalry.

Other key developments included:

Hotline Agreement (1963): Established direct communication between Washington and Moscow to prevent misunderstandings during crises.

Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT I): Negotiated under President Nixon, these agreements froze certain categories of nuclear weapons and signaled a commitment to strategic restraint.

Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty (1972): Limited missile-defense systems, reinforcing the logic of deterrence by preventing destabilizing technological competition.

These efforts illustrated that détente did not eliminate competition—it instead created mechanisms to reduce the risk that competition would escalate into nuclear war.

Détente and Global Strategy

For the United States, détente served multiple purposes. It aimed to manage relations with the Soviet Union, reduce defense spending pressures, and create space for strategic engagement elsewhere. It also complemented the Nixon Doctrine, which called for allies to take greater responsibility for their own defense, thereby reducing direct U.S. involvement in some regional conflicts.

Important shifts associated with détente included:

Triangular diplomacy, in which the United States used improved relations with China to gain leverage over the Soviet Union

Continued ideological rivalry, especially in the developing world

Efforts to stabilize Europe through the Helsinki Accords (1975), which addressed borders, human rights, and economic cooperation

This image shows major European and American leaders signing the Helsinki Final Act in 1975, illustrating détente’s expansion into multilateral agreements on security and human rights. The photograph highlights how superpower rivalry shifted toward structured coexistence. It includes additional participating leaders not individually named in the notes but all integral to the accords. Source.

Although détente suggested coexistence, it did not fundamentally resolve Cold War tensions.

Limits and Critiques of Détente

Détente faced growing criticism within the United States. Some policymakers and citizens argued that cooperation made the nation appear weak or conceded too much to communist powers. Others believed détente failed to address Soviet actions in the Third World, where proxy conflicts continued in Latin America, Africa, and Asia.

Critics within government emphasized:

Concerns over Soviet military buildup

Fear that arms agreements provided only symbolic restraint

Belief that human rights issues were sidelined in favor of strategic convenience

By the late 1970s, tensions resurfaced sharply. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, combined with domestic political pressures, contributed to the erosion of détente and the reemergence of more confrontational rhetoric.

Long-Term Significance

The alternating pattern of confrontation and détente highlighted the complexity of Cold War diplomacy. While ideological rivalry remained constant, both superpowers recognized the need for stability in a nuclear world. The era demonstrated that Cold War conflict was not linear but instead moved through phases shaped by leadership, global events, and strategic necessity.

FAQ

Leadership styles strongly influenced the tone of superpower relations. Nikita Khrushchev’s unpredictable diplomacy encouraged both crisis and limited cooperation, but his removal opened the door to a more measured Soviet approach under Brezhnev.

On the American side, Nixon and his adviser Henry Kissinger pursued pragmatic, strategic engagement rather than ideological confrontation.

This combination of personal diplomacy and strategic calculation helped create conditions for negotiation that had been absent in earlier Cold War phases.

Growing disillusionment with prolonged Cold War spending, alongside social upheavals of the late 1960s, contributed to public appetite for reduced tensions.

Many Americans viewed arms control as a way to reallocate resources toward domestic priorities.

Additionally, fatigue from the Vietnam War made diplomatic solutions more appealing than costly military commitments abroad.

Superpower leaders accepted that their ideological conflict was irreconcilable, but both recognised the need to stabilise nuclear rivalry.

Arms-control negotiations focused on measurable, enforceable limits, making them more feasible than trying to resolve political or ideological divisions.

This practical approach allowed détente to progress even while propaganda, espionage, and competition in the developing world continued.

The growing hostility between China and the Soviet Union gave the United States an opportunity to reshape Cold War dynamics.

When the U.S. improved relations with China in the early 1970s, Moscow feared strategic isolation.

In response, Soviet leaders became more open to negotiations with Washington:

• to prevent a U.S.–China alignment from threatening Soviet power

• to gain diplomatic flexibility without escalating military competition

Détente reduced immediate tensions but could not overcome deep ideological divisions or global competition.

Regional conflicts in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia continued to serve as proxy battlegrounds, undermining trust.

Hardliners in both nations criticised concessions and argued that the rival superpower exploited diplomacy for advantage.

Ultimately, divergent expectations—Washington’s focus on behaviour and human rights, Moscow’s emphasis on recognising spheres of influence—created persistent friction that re-emerged by the late 1970s.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Identify one major factor that contributed to the development of détente between the United States and the Soviet Union in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Award up to 3 marks:

• 1 mark for identifying a valid factor (e.g., economic pressures from the arms race, recognition of the dangers of nuclear war, desire for greater stability).

• 1 additional mark for briefly explaining how that factor encouraged a move towards détente.

• 1 additional mark for contextualising the factor within Cold War developments (e.g., post–Cuban Missile Crisis caution, domestic pressures in both superpowers).

Maximum: 3 marks.

(4–6 marks)

Explain how the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT I) and the Helsinki Accords reflected broader shifts in United States foreign policy from confrontation to détente during the 1970s.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Award up to 6 marks:

• 1–2 marks for accurately describing the purpose or outcomes of SALT I (e.g., freezing certain nuclear stockpiles, limiting anti-ballistic missile systems).

• 1–2 marks for accurately describing the purpose or outcomes of the Helsinki Accords (e.g., recognising European borders, establishing human rights commitments, promoting East–West cooperation).

• 1–2 marks for explaining how both agreements demonstrated a shift from direct confrontation toward managed coexistence, reduced tensions, or a more structured diplomatic framework.

Maximum: 6 marks.