AP Syllabus focus:

‘Americans debated the appropriate power of the executive branch in conducting foreign and military policy during the Cold War.’

During the Cold War, shifting global threats and ideological rivalry intensified debates over presidential authority, prompting policymakers and citizens to question how far executive power should extend in foreign and military affairs.

Expanding Presidential Power in a Bipolar World

The onset of the Cold War encouraged U.S. leaders to centralize foreign policy decision-making in the executive branch, justified by the need for rapid, flexible responses to perceived Soviet aggression. Presidents argued that global containment required secrecy, swift action, and unified command, strengthening the national security state and reshaping expectations about executive leadership.

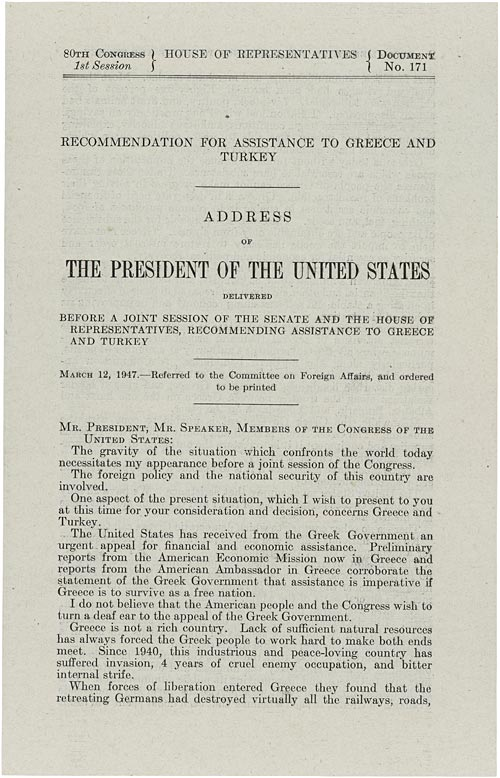

This printed page shows President Harry S. Truman’s 1947 message to Congress outlining the Truman Doctrine. It highlights an early Cold War moment when presidential initiative shaped U.S. global leadership and helped justify expanded executive authority. The document includes more detailed discussion of Greece and Turkey than students need for this subtopic. Source.

The Commander-in-Chief Role and Constitutional Interpretation

Cold War crises elevated the president’s constitutional role as commander-in-chief, often broadening its meaning to encompass not only directing military operations but also shaping strategic doctrine and covert activity.

Commander-in-Chief: The constitutional role granting the president authority over military forces and responsibility for directing national defense policy.

This expanded interpretation drew support from Congress at times, particularly when policymakers feared communist advances, but it also sparked growing unease about the concentration of power in the Oval Office.

Institutional Growth and the National Security State

Creation of New Executive-Centered Agencies

Cold War policymaking accelerated the development of a permanent national security bureaucracy that answered primarily to the president.

Key components included:

National Security Council (NSC): Coordinated diplomatic, military, and intelligence strategies.

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA): Oversaw intelligence gathering and covert operations, often conducted with limited public oversight.

Department of Defense (DoD): Unified military branches under centralized civilian control to streamline Cold War strategy.

These institutions allowed presidents to manage crises swiftly, but critics argued they created opaque channels of decision-making that distanced foreign policy from democratic accountability.

The Rise of Covert Action

Presidents from Truman onward increasingly relied on covert interventions to influence political outcomes abroad while avoiding full-scale war. CIA activities in Iran (1953), Guatemala (1954), and other regions illustrated an executive preference for tools that minimized public scrutiny but carried long-term geopolitical consequences. Supporters viewed covert action as a cost-effective containment measure, while opponents warned it circumvented constitutional checks and risked unintended instability.

Congressional Responses and Growing Concerns

Delegation and Later Retrenchment

In the early Cold War, Congress often ceded broad authority to the president, approving military spending, intelligence expansion, and general containment goals. Legislators feared appearing weak on communism, and bipartisan consensus limited challenges to executive initiatives. However, as the Cold War progressed, concerns about overreach grew, especially as the public learned more about covert operations, surveillance, and unilateral military actions.

War-Making Power and the Limits of Authority

Presidential decisions to commit troops without formal declarations of war—such as in Korea (1950)—intensified debates over constitutional limits. Although many lawmakers initially supported these actions to resist communism, the lack of a formal war declaration prompted questions about whether presidents were bypassing Congress’s constitutional authority to decide on war.

War Powers: The distribution of authority between Congress and the president regarding the initiation, conduct, and oversight of military operations.

These concerns deepened as later conflicts, especially Vietnam, revealed the risks of granting broad, open-ended military discretion to the executive branch.

Public Expectations and the Politics of National Security

Cold War Anxiety and Presidential Leadership

Many Americans believed the president should act decisively to counter communist threats, reinforcing expectations of strong executive leadership. The nuclear age heightened these attitudes, as rapid decision-making seemed essential in crises such as the Berlin Blockade, Korean War, and Cuban Missile Crisis.

This photograph depicts President John F. Kennedy and members of the ExComm deliberating during the Cuban Missile Crisis. It illustrates how nuclear-era tensions required swift presidential decision-making with a tightly controlled advisory circle. The surrounding article provides more detail than needed for this subtopic, but the image clearly reflects Cold War executive power in action. Source.

Media, Secrecy, and Public Trust

As media coverage of foreign policy expanded, secrecy surrounding executive actions sometimes clashed with democratic expectations. Revelations about covert operations, domestic surveillance, and misrepresented military assessments produced growing skepticism. These tensions highlighted a central Cold War dilemma: how to balance effective national defense with transparent, accountable governance.

The Cold War Presidency as a Long-Term Institution

The “Imperial Presidency” Debate

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, critics described the Cold War executive as an “imperial presidency,” suggesting that decades of global tension had entrenched habits of unilateral action and limited oversight. While some argued strong presidential power was necessary for global leadership, others pushed for reforms to restore congressional authority and strengthen democratic checks.

Containment and the Permanence of Executive Authority

Containment strategy demanded continuous vigilance, making foreign policy a largely executive-driven arena. The expectation that presidents would respond swiftly to crises—whether in Europe, Asia, or elsewhere—solidified a political culture that treated the executive branch as the primary guardian of national security, influencing debates long after the Cold War’s early decades.

This map illustrates the geopolitical division of Europe into Western-aligned, Soviet-aligned, and neutral states during the Cold War. It helps contextualize why U.S. presidents faced persistent international pressures that strengthened executive authority in foreign policy. The map contains additional economic alliance detail beyond syllabus requirements, but these elements primarily add contextual clarity. Source.

FAQ

Intelligence reports in the late 1940s and early 1950s frequently warned of potential Soviet expansion, encouraging presidents to take swift, sometimes unilateral, actions.

These assessments justified rapid responses such as emergency military deployments or covert operations.

They also fostered a mindset that uncertainty itself was a national security threat, strengthening the argument for concentrated executive authority.

Cold War confrontations often unfolded quickly, making lengthy congressional debate appear impractical or risky.

Policymakers argued that:

• Nuclear-era threats required instant communication and decision-making.

• Diplomatic opportunities could vanish if delayed.

• Revealing sensitive plans during legislative debate could compromise national security.

This perception contributed significantly to arguments for enhanced presidential leadership.

Because many Cold War operations were highly classified, the public often had limited awareness of the scope of presidential actions.

This secrecy created a gap between official statements and actual policy, which later fuelled suspicion when covert activities were revealed.

It also complicated debates over executive authority, as citizens and some legislators struggled to judge decisions they could not fully see.

Presidential legal teams increasingly interpreted constitutional and statutory authority in ways that supported broad executive discretion.

Common approaches included:

• Stretching commander-in-chief responsibilities to justify new forms of military engagement.

• Reinterpreting existing authorisations to permit covert or indirect actions.

• Advising that congressional consultation was optional rather than required in emergencies.

These internal legal frameworks shaped long-term expectations about foreign policy leadership.

Advances in communications and surveillance technologies allowed presidents to monitor events globally and respond in near real time.

This increased capacity encouraged the belief that the president should personally direct high-stakes operations, especially those involving nuclear alerts or reconnaissance systems.

Technological speed made older, more deliberative models of shared authority appear outdated, reinforcing executive primacy in crisis management.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which Cold War tensions contributed to an expansion of presidential power in the United States.

Question 1

Explain one way in which Cold War tensions contributed to an expansion of presidential power in the United States.

Marks:

• 1 mark for a general statement identifying a link between Cold War tensions and increased presidential authority.

• 2 marks for a clear explanation connecting a specific Cold War condition (for example, the need for rapid decision-making, nuclear threat, or containment strategy) to expanded presidential action or institutional growth.

• 3 marks for a developed explanation showing how the Cold War environment directly justified greater executive control (for example, use of covert operations, commander-in-chief powers, or reliance on national security agencies) and referring accurately to historical context.

Acceptable answers may include: Cold War urgency leading to centralisation of foreign policy; the president’s role in directing covert operations; the tendency to deploy troops without formal declarations of war; growth of the national security state.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Assess the extent to which Cold War crises between 1945 and 1980 intensified debates over the appropriate balance of power between Congress and the president in matters of foreign and military policy.

Question 2

Assess the extent to which Cold War crises between 1945 and 1980 intensified debates over the appropriate balance of power between Congress and the president in matters of foreign and military policy.

Marks:

• 1–2 marks for a basic description of Cold War crises with limited or no connection to debates over executive versus legislative power.

• 3–4 marks for a structured explanation linking specific crises (for example, the Korean War, Cuban Missile Crisis, or early covert actions) to rising concerns about expanded presidential authority or reduced Congressional oversight.

• 5–6 marks for a well-developed argument addressing both sides of the debate, using accurate historical examples, and showing how particular events increased scrutiny of presidential decision-making while also noting moments when Congress supported or delegated power to the executive.

High-scoring answers should address: fears of an “imperial presidency”; congressional unease over undeclared wars; secrecy surrounding intelligence operations; growing public concern; and early bipartisan support for containment that initially strengthened presidential latitude.