AP Syllabus focus:

‘Progress toward racial equality was slow as resistance to desegregation forced federal leaders to weigh enforcement, politics, and constitutional authority.’

Federal authority expanded during early civil rights battles as southern resistance intensified. Pressure mounted on national leaders to balance legal enforcement, regional opposition, and political consequences.

Federal Authority After Brown v. Board of Education

Following the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, federal officials faced the challenge of implementing desegregation in states where political leaders openly refused compliance. Southern policymakers developed strategies to circumvent or delay federal mandates, prompting national debate over the scope of federal power.

Constitutional Foundations of Federal Enforcement

The federal government’s civil rights role rested on the Fourteenth Amendment, which requires states to provide equal protection under the law. Federal courts thus became central sites of conflict, ordering desegregation and reviewing southern tactics designed to preserve segregation. As federal rulings accumulated, state officials escalated obstructionist policies, framing their actions as defenses of states’ rights, a political doctrine asserting that state governments hold primary authority over education and local institutions.

States’ rights: A political principle claiming that state governments retain autonomy and authority over local matters, limiting federal intervention.

Federal leaders, mindful of Cold War pressures to demonstrate democratic equality, were forced to respond when state resistance threatened constitutional order and international credibility.

Organized Southern Resistance

Southern resistance emerged as a coordinated movement to block integration through legal maneuvers, political messaging, and public mobilization.

The Southern Manifesto and Political Defiance

In 1956, 101 members of Congress issued the Southern Manifesto, denouncing Brown as a violation of judicial authority and encouraging states to resist implementation. The document helped consolidate regional opposition and signaled that resistance was not only cultural but also institutional.

Massive Resistance Campaigns

Governors, legislatures, and school boards adopted Massive Resistance, a strategy of aggressive obstruction that included:

Passing state laws to circumvent or nullify federal court orders.

Closing public schools rather than integrating them.

Redirecting public funds to private, segregated “freedom of choice” or “segregation academy” schools.

Harassing civil rights activists and local Black leaders to deter demands for compliance.

These policies created stalemates in which federal judges issued orders that state officials refused to implement, raising questions about the federal government’s capacity to enforce its own rulings.

Federal Intervention and the Limits of Executive Power

Presidential administrations in the 1950s navigated political risk in addressing civil rights crises. Although federal authority was clear in theory, using it required weighing southern backlash, national public opinion, and electoral considerations.

Eisenhower and the Little Rock Crisis

In 1957, the attempt to integrate Little Rock Central High School became a defining confrontation. Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus used the National Guard to block nine Black students from entering the school. Repeated federal court orders failed to secure compliance, demonstrating the limits of judicial authority without executive enforcement.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower eventually invoked his constitutional duty to ensure federal law was executed.

U.S. Army soldiers from the 101st Airborne Division escort African American students to Little Rock Central High School in 1957, enforcing federal desegregation orders over state resistance. The image illustrates the federal government’s readiness to deploy military authority when states openly defied the Supreme Court’s mandate in Brown v. Board of Education. While tied to a specific crisis, it reflects broader federal efforts to overcome southern obstruction. Source.

He:

Placed the Arkansas National Guard under federal control.

Deployed the 101st Airborne Division to escort students and enforce the court order.

This intervention illustrated the federal government’s willingness to act when state resistance openly defied constitutional authority.

Balancing Federal Power with Political Realities

Even when presidents intervened, enforcement of desegregation remained inconsistent. National leaders faced competing pressures: the need to uphold the rule of law, fears of alienating white southern voters, and Cold War imperatives to project moral leadership abroad.

Judicial and Legislative Actions

As presidential action remained limited, federal courts increasingly issued rulings prohibiting evasion tactics. At the same time, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1957, the first major civil rights legislation since Reconstruction. Although modest, it signaled federal recognition that resistance in the South was undermining constitutional guarantees.

Local Resistance and Community-Level Conflict

Southern communities continued to resist through social intimidation, economic reprisals, and political dominance by segregationist leaders. These actions:

Slowed meaningful progress toward racial equality.

Required prolonged federal oversight and repeated litigation.

Reinforced the national debate over how far the federal government should go to regulate state actions.

Federal leaders thus confronted an ongoing dilemma: the constitutional obligation to protect civil rights versus the political risks of using forceful intervention.

Federal Intervention and the Limits of Executive Power

Presidential administrations in the 1950s navigated political risk in addressing civil rights crises. Although federal authority was clear in theory, using it required weighing southern backlash, national public opinion, and electoral considerations.

Although federal authority was clear in theory, using it required weighing southern backlash, national public opinion, and electoral considerations.

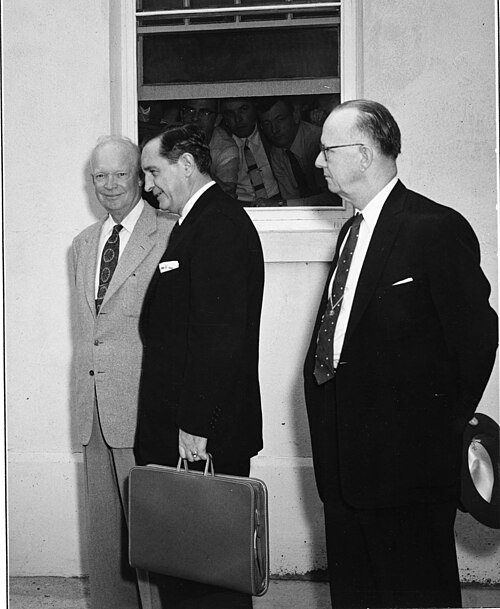

President Dwight D. Eisenhower meets with Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus and Congressman Brooks Hays following negotiations over school integration in Little Rock. The photograph highlights the federal government’s attempts to use diplomacy and political pressure before deploying troops. While depicting one specific meeting, it illustrates the broader tension between federal authority and southern political resistance. Source.

Long-Term Impact on Federal–State Relations

Federal responses to southern resistance reshaped understandings of constitutional authority. The conflicts of the 1950s established that:

The federal government held ultimate responsibility for enforcing civil rights.

States could not nullify or ignore federal court decisions.

National leaders would increasingly be judged on their willingness to confront violations of constitutional rights.

These developments set the stage for more expansive federal civil rights actions in the 1960s, as activists pressed Washington to use its full power to dismantle segregation.

FAQ

Southern governors commonly argued that education fell under state authority, claiming the federal government and the Supreme Court had exceeded constitutional limits.

They also appealed to regional traditions, insisting that rapid desegregation would disrupt social order.

Some portrayed resistance as protecting local democracy, asserting that federal enforcement undermined the will of white southern voters.

Many school boards adopted gradualist or technical methods designed to avoid immediate compliance. These included:

Introducing pupil placement tests that disproportionately affected Black students

Creating complex transfer procedures

Redrawing school zones in ways that preserved racial separation

Such strategies appeared legal on the surface, delaying enforcement without openly defying federal courts.

Federal judges increasingly scrutinised laws and policies designed to produce segregation indirectly.

Courts issued rulings striking down evasive tactics, arguing that compliance required meaningful—not symbolic—integration.

This judicial shift gradually closed loopholes, compelling states to adopt more transparent methods of obstruction or move toward compliance.

Yes. National sentiment shaped presidential calculations, as many Americans outside the South viewed open defiance of federal authority as unacceptable.

However, there was also reluctance among some northern voters to support strong intervention, especially if it appeared likely to provoke violence or deepen sectional tensions.

This mixed public reaction contributed to inconsistent and cautious federal enforcement.

Federal engagement in desegregation prompted the expansion of bureaucratic structures involved in civil rights oversight.

Key developments included:

Growth of the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division

Increased cooperation between federal courts and executive agencies

Development of monitoring procedures for school compliance

These administrative tools laid groundwork for stronger federal action during the 1960s.

Practice Questions

Explain one reason why the federal government intervened in the Little Rock school integration crisis of 1957. (1–3 marks)

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

• 1 mark: Identifies a valid reason (e.g., to enforce the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education ruling).

• 2 marks: Provides a reason with some explanation (e.g., the state’s refusal to comply with court orders required federal intervention).

• 3 marks: Fully explains the reason with clear contextual understanding (e.g., Eisenhower intervened because Governor Faubus’s use of the National Guard to block integration directly challenged federal authority and the rule of law, compelling the president to uphold constitutional responsibilities).

Assess the extent to which southern resistance in the 1950s limited federal efforts to enforce desegregation. (4–6 marks)

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

• 4 marks: Offers a general explanation of southern resistance and its impact, with limited detail or development.

• 5 marks: Provides a well-supported analysis showing how resistance tactics (such as Massive Resistance, school closures, legal obstruction, and political defiance) hindered federal enforcement, with some contextual or specific examples.

• 6 marks: Presents a fully developed assessment with sustained analysis of both the limitations created by southern resistance and the federal responses. Demonstrates nuanced understanding (e.g., although resistance slowed desegregation and forced the federal government to act cautiously, key interventions such as Little Rock revealed that federal authority ultimately prevailed when directly challenged).