AP Syllabus focus:

‘Postwar decolonization and Asian nationalist movements shaped Cold War choices as both sides sought allies among new nations, many of which stayed nonaligned.’

The collapse of European empires after World War II created new nations whose nationalist ambitions, strategic locations, and political uncertainty reshaped U.S. Cold War decision-making and helped set the stage for conflict in Vietnam.

The Global Context of Decolonization

After 1945, decolonization—the process by which imperial powers relinquished political authority over colonies—accelerated across Asia and Africa. The weakening of European states, rising nationalist movements, and new international expectations about self-determination reconfigured global politics. The United States and the Soviet Union both saw emerging nations as potential partners, intensifying Cold War competition in formerly colonized regions.

Self-determination: The principle that peoples have the right to choose their own political status and form of government.

As independence movements gained momentum, U.S. policymakers struggled to balance ideological commitments to freedom with strategic fears that revolutionary movements might adopt communist models. This tension shaped early American involvement in Southeast Asia.

Asian Nationalist Movements and Shifting Power

The End of European Empire in Asia

Japan’s defeat in 1945 dismantled its wartime empire, creating a political vacuum in Southeast Asia. European powers—especially France, the Netherlands, and Britain—attempted to reassert authority, but they faced well-organized nationalist movements energized by wartime mobilization. Asia became a key arena where Cold War objectives intersected with the aspirations of local leaders.

Vietnam and the Legacy of Colonial Rule

French Indochina experienced one of the strongest nationalist surges. Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh blended nationalism with communist ideology, declaring independence in 1945. His goals reflected local aspirations for liberation from French rule rather than a simple extension of Soviet or Chinese influence. The United States initially hesitated, recognizing the popularity of anticolonial sentiment but becoming increasingly wary of communist victories after 1949.

Across Asia, nationalist movements pushed European empires into retreat, and Vietnam’s struggle was part of this wider wave of post-1945 decolonization.

This map shows political changes in Asia after World War II as former colonies gained independence and new states emerged. It highlights the rapid decline of European empires and situates the independence of Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia within a broader regional transformation. Additional Asian independence data is included beyond the immediate AP syllabus focus. Source.

The Cold War and Strategic Realignments

Why Decolonization Mattered to U.S. Leaders

Emerging nations were not passive objects of superpower rivalry. Instead, many pursued nonalignment, seeking to avoid entanglement in Cold War blocs. Their policy autonomy concerned U.S. officials, who feared that political instability or neutral diplomacy might create openings for communist expansion.

The “Domino Theory” and Southeast Asia

The belief that political changes in one nation could influence others nearby became a central framework for analyzing regional shifts.

Domino Theory: The Cold War idea that if one nation fell under communist rule, neighboring states would soon follow, threatening wider regional stability.

This conceptualization linked decolonization directly to security concerns. In the eyes of American officials, the loss of newly independent states to communist movements—whether internally driven or externally supported—would signal a failure of U.S. containment strategies.

Vietnam and the Road to War

Reassessing French Colonialism

As France attempted to reestablish its colonial presence in Indochina, conflict erupted between French forces and Ho Chi Minh’s Viet Minh. The United States, concerned about communist gains after the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 and the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, increased financial and military support for France. Although this contradicted American rhetoric about freedom and independence, Cold War priorities dominated policy choices.

Before the war for independence, Vietnam was part of French Indochina, a colonial federation that also included Laos and Cambodia.

This locator map highlights the geographic extent of French Indochina in 1945, situating Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia within a single colonial federation. It supports understanding of the political framework inherited by Vietnamese nationalists. The map adds no significant detail beyond geographic placement. Source.

Division at Geneva

The 1954 Geneva Accords ended France’s colonial war but created the temporary division of Vietnam at the 17th parallel. Although intended as a short-term political arrangement pending national elections, the agreement deepened geopolitical fault lines. The United States refused to sign the accords and instead fostered an anticommunist government in South Vietnam under Ngo Dinh Diem. This commitment signaled a deeper American involvement rooted in fears that a united Vietnam under Ho Chi Minh would align with communist powers.

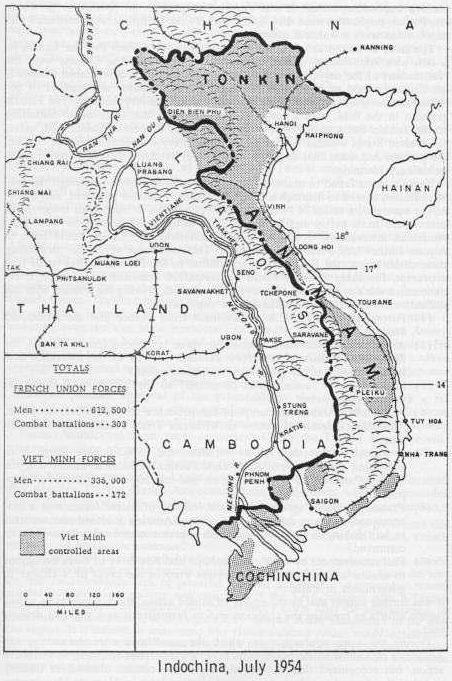

By the time of the Geneva Conference in 1954, Viet Minh forces controlled large swaths of northern and central Vietnam, convincing French leaders to accept a negotiated settlement.

This map illustrates Viet Minh territorial control and French Union positions near the end of the First Indochina War, revealing the military pressures driving French acceptance of the Geneva settlement. It clarifies why territory became a central issue in negotiating Vietnam’s temporary division. The image includes extra military detail—such as unit counts—not required by the AP syllabus. Source.

One sentence here before next definition block ensures proper formatting compliance.

Containment: The U.S. Cold War strategy aimed at preventing the expansion of communist power through political, military, and economic measures.

Local Dynamics and Superpower Decisions

Although Cold War concerns shaped U.S. strategy, the roots of the conflict lay equally in Vietnamese nationalism, regional rivalries, and disputes over legitimacy. Many Vietnamese rejected foreign domination—whether French, Japanese, or American—as incompatible with their aspirations for independence. U.S. leaders, however, interpreted events primarily through the lens of global ideological struggle.

Nonalignment and Its Limits

Many postcolonial nations joined the Non-Aligned Movement, refusing formal alliance with either the United States or the Soviet Union. For U.S. officials, this stance posed both diplomatic challenges and opportunities. Nations that sought economic aid from multiple sources could leverage Cold War tensions to their advantage, complicating American expectations about loyalty and influence.

Escalation Toward Direct U.S. Involvement

By the late 1950s, deteriorating political conditions in South Vietnam, the resurgence of communist-led insurgency, and the belief that failure in Vietnam would undermine U.S. credibility worldwide pushed policymakers toward deeper engagement. Decolonization did not create the Vietnam War on its own, but it produced a volatile landscape in which Cold War fears shaped increasingly interventionist decisions.

Looking Ahead: The Broader Significance

Decolonization reshaped global politics by bringing new nations into the international system. For the United States, these developments created both diplomatic challenges and strategic pressures, contributing to the path toward major military involvement in Vietnam.

FAQ

Vietnam was not politically homogeneous; religious, regional and class divisions influenced allegiances and helped structure early conflicts.

Examples include:

• The strength of Viet Minh networks in rural northern areas

• The presence of religious sects and rival nationalist groups in the south

• Conservatives supporting Ngo Dinh Diem’s regime despite widespread scepticism

These divisions complicated American assessments and led to policies that often misread local dynamics.

Japan’s occupation undermined European authority by removing colonial officials and exposing weaknesses in imperial rule. This opened political space for local leaders to organise and mobilise support.

In Vietnam, the Viet Minh gained legitimacy by resisting Japan and providing limited governance during the occupation.

Across Southeast Asia, wartime upheaval accelerated political consciousness and weakened the assumption that European return after 1945 was inevitable.

Many saw Cold War alignment as compromising their newly won sovereignty and risking entanglement in bloc politics.

Key motivations included:

• Desire to attract aid from multiple powers

• Fear of becoming a proxy battleground

• Ideological commitments to nonalignment or neutralism

• Internal divisions that made rigid alignment politically risky

Dien Bien Phu demonstrated that a determined nationalist force could defeat a major European colonial power using a combination of guerrilla tactics and conventional operations.

The victory signalled to other nationalist groups that colonial regimes were vulnerable, and it alerted US policymakers to the limits of European control.

It also increased American concern that similar movements elsewhere might succeed if not countered politically or militarily.

For Vietnamese nationalists, the temporary division of Vietnam frustrated their goal of unifying the country under a single government, which they believed would happen through national elections.

For the United States, the proposed elections carried the risk of a Viet Minh victory, which officials feared would strengthen communist influence in Asia.

Both sides therefore viewed the arrangement as a stopgap rather than a durable settlement.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which post-1945 decolonisation in Asia influenced early US involvement in Vietnam.

Question 1

Award up to 3 marks:

1 mark for identifying a valid influence (e.g., the rise of nationalist movements challenging European empires).

1 mark for explaining how this created strategic concerns for the United States (e.g., fear that nationalist revolutions might align with communism).

1 mark for linking this influence directly to early US policy or actions in Vietnam (e.g., increased support for France, concerns about Ho Chi Minh’s dual nationalist and communist identity).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using your knowledge of the period 1945–1954, analyse the extent to which nationalist movements in Southeast Asia, rather than Cold War rivalry, shaped the United States’ road to war in Vietnam.

Question 2

Award up to 6 marks:

1–2 marks for describing relevant factual material about decolonisation or Cold War rivalry (e.g., weakening of European empires, Viet Minh nationalist aims, US fears following 1949 and the Korean War).

1–2 marks for explaining how nationalist movements shaped events (e.g., Vietnamese anti-colonial demands driving conflict, local dynamics prompting French withdrawal and US reassessment).

1–2 marks for analysis of the relative importance of nationalist movements versus Cold War motivations, supported by specific evidence (e.g., Geneva Accords, French defeat at Dien Bien Phu, US refusal to sign the settlement, concern for containment and the domino theory).

High-level responses should show explicit judgement about the extent to which nationalist movements, as opposed to Cold War competition, influenced the US road to war.