AP Syllabus focus:

‘To contain communist expansion, the United States undertook major military engagement in Vietnam, escalating involvement through the 1960s.’

U.S. involvement in Vietnam intensified as leaders pursued containment, expanding advisory roles into sustained military operations. Escalation reflected Cold War priorities, domestic politics, and evolving perceptions of communist threats.

Escalating Commitment in the Early 1960s

The origins of U.S. escalation in Vietnam lay in the broader Cold War aim of containment, the strategy of preventing the expansion of communism beyond existing borders.

Containment: A Cold War strategy advocating the prevention of communist expansion through political, economic, and military measures.

Although initial involvement began under Eisenhower through financial and advisory support to South Vietnam, major escalation occurred under President John F. Kennedy, who expanded the number of Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG) personnel.

U.S. and South Vietnamese soldiers study a map under the guidance of a U.S. Army adviser, illustrating the expanded MAAG training mission in the early 1960s. The photo highlights how escalation began with advisory roles before the arrival of major combat units. Additional contextual details appear that go beyond the specific syllabus emphasis but support understanding of American involvement’s early phase. Source.

Kennedy viewed South Vietnam as a critical test of U.S. resolve, believing that failing to support the South Vietnamese government would undermine American credibility across Asia.

Key developments included:

A dramatic increase in U.S. military advisers.

Deployment of Special Forces to train South Vietnamese troops.

Support for strategic hamlets aimed at separating civilians from communist insurgents.

However, political instability—culminating in the U.S.-supported coup against President Ngo Dinh Diem in 1963—deepened American entanglement. Washington’s willingness to influence South Vietnamese leadership marked a turning point toward more direct responsibility for the war’s outcome.

Johnson’s Escalation and the Logic of Containment

President Lyndon B. Johnson transformed a limited engagement into a major conflict. He feared that withdrawal would signal weakness to the Soviet Union and China, potentially triggering what policymakers described as the Domino Theory.

Johnson’s escalation unfolded through several interconnected developments:

From Advisory Role to Active Combat

Two major events accelerated U.S. involvement:

The Gulf of Tonkin Incident (1964), in which U.S. ships reported attacks by North Vietnamese patrol boats.

Passage of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, granting Johnson broad authority to use military force without a formal declaration of war.

Gulf of Tonkin Resolution: Congressional authorization permitting the president to take “all necessary measures” to repel attacks and prevent further aggression in Southeast Asia.

This resolution became the legal foundation for massive troop deployments and sustained bombing campaigns.

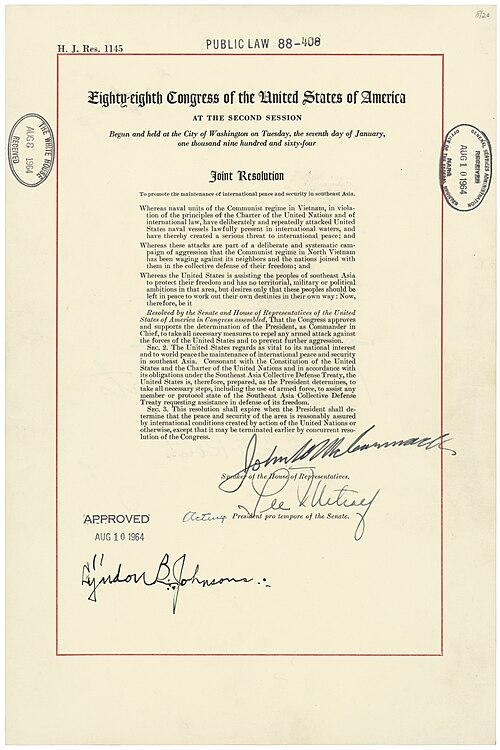

This archival scan of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution shows the congressional authorization that empowered the president to expand military operations in Vietnam. It visually captures how escalation gained formal legal grounding. The document includes stamps and signatures that exceed syllabus requirements but reinforce the historical authenticity of the moment. Source.

The introduction of ground combat units in 1965 marked a shift from supporting the South Vietnamese military to conducting offensive operations.

Operation Rolling Thunder and Military Strategy

Johnson authorized Operation Rolling Thunder, a prolonged aerial bombing campaign designed to pressure North Vietnam and boost South Vietnamese morale. The campaign reflected assumptions that U.S. technology and firepower could force diplomatic concessions.

Escalation relied on two key approaches:

Using airpower to disrupt supply networks such as the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

This map illustrates the Vietnam War theatre, including the Ho Chi Minh Trail, a central focus of U.S. bombing during escalation. It shows how geography shaped containment strategy and the challenges of interdicting communist supply routes. The map includes additional details such as B-52 flight paths not required by the syllabus but useful for understanding operational context. Source.

Deploying large numbers of U.S. combat troops to engage communist forces directly.

General William Westmoreland pursued a strategy of war of attrition, aiming to wear down enemy forces through superior U.S. firepower. This approach prioritized body counts as indicators of progress, though it often failed to account for the resilience and adaptability of the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army.

Challenges and Limitations of U.S. Power

As involvement deepened, policymakers confronted the limits of American military and political influence.

Guerrilla Warfare and Terrain

Communist forces employed guerrilla tactics—hit-and-run attacks, tunnels, ambushes—that offset U.S. technological advantages. Dense terrain, monsoon weather, and unfamiliar environments further complicated operations.

South Vietnamese Instability

South Vietnam faced chronic leadership changes, corruption, and limited popular support, undermining U.S. goals. American officials struggled to build a stable, legitimate ally capable of resisting the communist insurgency.

International Context and Cold War Constraints

Containment shaped every decision. U.S. leaders feared that excessive force risked provoking direct confrontation with China or the Soviet Union, while insufficient force risked losing Vietnam. These constraints produced a calibrated but ultimately ineffective escalation process.

Domestic Pressures and Shifting Public Perception

As troop levels and casualties increased, public support eroded. While early decisions reflected bipartisan Cold War consensus, the growing visibility of combat and media coverage intensified scrutiny.

Key domestic developments included:

Rising skepticism about official claims of progress.

Mounting antiwar activism, especially among students.

Congressional debate over the scope of presidential war powers.

The gap between military reports and battlefield realities contributed to what journalists termed the “credibility gap,” weakening trust in government.

Containment and the Long Road to Stalemate

By the late 1960s, escalation failed to produce decisive results. Despite immense firepower and personnel, U.S. forces could not eliminate communist commitment or overcome structural weaknesses in South Vietnam. The pursuit of containment resulted in a costly stalemate that set the stage for later policy shifts, including Vietnamization and negotiations under President Nixon—developments beyond the scope of this subsubtopic.

U.S. escalation in Vietnam thus reflected the Cold War imperative to contain communism, the belief in American military superiority, and the political pressures shaping presidential decision-making.

FAQ

American intelligence agencies frequently reported that South Vietnam was at risk of collapse without increased US support. These assessments stressed the organisational strength of the Viet Cong and the political instability in Saigon.

Such reports convinced policymakers that limited aid and advisory roles would be insufficient. Escalation appeared necessary to prevent communist consolidation in the South and to preserve US credibility in the wider Cold War context.

Many officials believed American technological superiority could compensate for South Vietnam’s weaknesses. Radar-guided bombing, jet aircraft, helicopters and advanced communications systems were thought to offer decisive advantages.

This technological confidence encouraged the belief that targeted air campaigns and rapid troop deployment could quickly weaken North Vietnamese and Viet Cong operations.

However, the adaptability of communist forces ultimately reduced the effectiveness of these capabilities.

Policymakers tended to interpret communist movements primarily through a Cold War ideological lens, assuming they were directed by Moscow or Beijing.

They underestimated the degree to which Vietnamese communism was driven by nationalism, anti-colonial sentiment and a long tradition of resistance to foreign control.

This misunderstanding led US leaders to assume the enemy’s morale could be broken more easily than proved possible.

Vietnam’s geography created major obstacles: thick forests, mountains, wetlands and an extensive river system made movement slow and hazardous.

Key challenges included:

Difficulty identifying guerrilla fighters within civilian populations.

Limited visibility for air operations during monsoon seasons.

Vulnerability of supply lines connecting dispersed US bases.

These logistical issues complicated attempts to impose military pressure on North Vietnam and the Viet Cong.

Once large numbers of troops were deployed, it became politically and militarily difficult to reverse course without appearing to concede defeat.

Escalation locked the United States into:

Protecting remote and strategically marginal bases.

Sustaining high levels of logistical support.

Maintaining public justification for continued involvement.

These commitments restricted later strategic flexibility, contributing to the prolonged stalemate of the late 1960s

Practice Questions

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Assess the extent to which the strategy of containment shaped US decisions to escalate the Vietnam War between 1964 and 1968.

Mark scheme:

1–2 marks for a clear explanation of the principle of containment and its Cold War context.

1–2 marks for specific evidence showing how containment influenced decisions (e.g., Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, Operation Rolling Thunder, introduction of combat troops, belief in preventing communist expansion).

1–2 marks for evaluation of the extent of containment’s influence, which may include:

consideration of additional factors (e.g., domestic political pressures, perceived credibility, instability of South Vietnam);

judgement about the relative importance of containment.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one reason why the United States escalated its military involvement in Vietnam during the mid-1960s.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying a valid reason (e.g., containment, Domino Theory, Gulf of Tonkin Resolution).

1 mark for describing the reason with relevant detail (e.g., belief that a communist victory would undermine US credibility or threaten other nations in Southeast Asia).

1 mark for explaining how this reason directly contributed to military escalation (e.g., justification for troop deployments or expansion of bombing campaigns).