AP Syllabus focus:

‘Employment grew in service sectors while manufacturing jobs fell; at the same time, union membership declined and labor’s influence weakened.’

The shift from manufacturing to services after 1980 transformed American economic life, employment patterns, and labor relations, reshaping workers’ experiences and altering the nation’s political landscape.

The Long Decline of U.S. Manufacturing

By the late twentieth century, the deindustrialization of the United States—the long-term reduction of manufacturing employment and industrial production in certain regions—accelerated as globalization, automation, and shifting corporate strategies reduced the number of factory jobs.

Deindustrialization: The sustained decline of manufacturing industries, often accompanied by job losses, plant closures, and economic restructuring.

Manufacturing had been a foundation of mid-century prosperity, providing stable, well-paid jobs, especially in the Midwest and Northeast. As industrial competition intensified abroad—particularly from Japan, later China—American companies sought cost efficiencies by automating production or relocating operations. Automation increased output but reduced labor demand, while the movement of factories to lower-wage regions or overseas further eroded the employment base of the so-called Rust Belt.

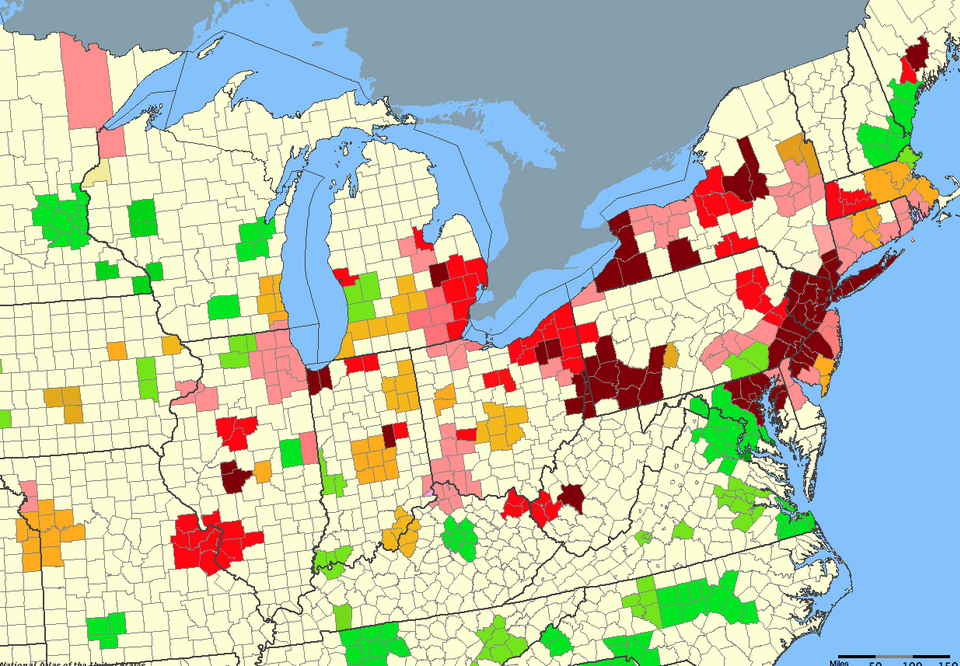

This map shows percentage changes in manufacturing jobs across U.S. metropolitan areas between the mid-1950s and 2002, with the Rust Belt experiencing some of the steepest declines. The color scale illustrates where manufacturing employment grew, stagnated, or fell, helping visualize the uneven effects of deindustrialization. The map includes detailed percentage categories beyond the syllabus, but students should focus on the broad regional pattern of major losses in traditional manufacturing centers. Source.

Communities dependent on steel, automobiles, textiles, and other durable goods industries confronted unemployment, shrinking local tax bases, and declining public services. These economic shocks carried significant cultural effects, weakening longstanding identities built around industrial work.

The Rise of a Service-Based Economy

As factory jobs disappeared, the service economy expanded rapidly and became the dominant sector of employment. Services include a broad array of non-manufacturing activities, ranging from retail and hospitality to healthcare, finance, education, and information technology.

Service economy: An economic structure in which most employment and value creation occur in sectors that provide services rather than produce goods.

Several forces drove this transformation:

Technological change, which increased productivity in manufacturing while generating new demand for information, customer support, health services, and logistics.

Increasing consumer spending on leisure, entertainment, travel, and personal services.

The rise of knowledge-based industries, including software development, financial services, and communications.

Economic globalization, which reorganized production networks and heightened reliance on international supply chains.

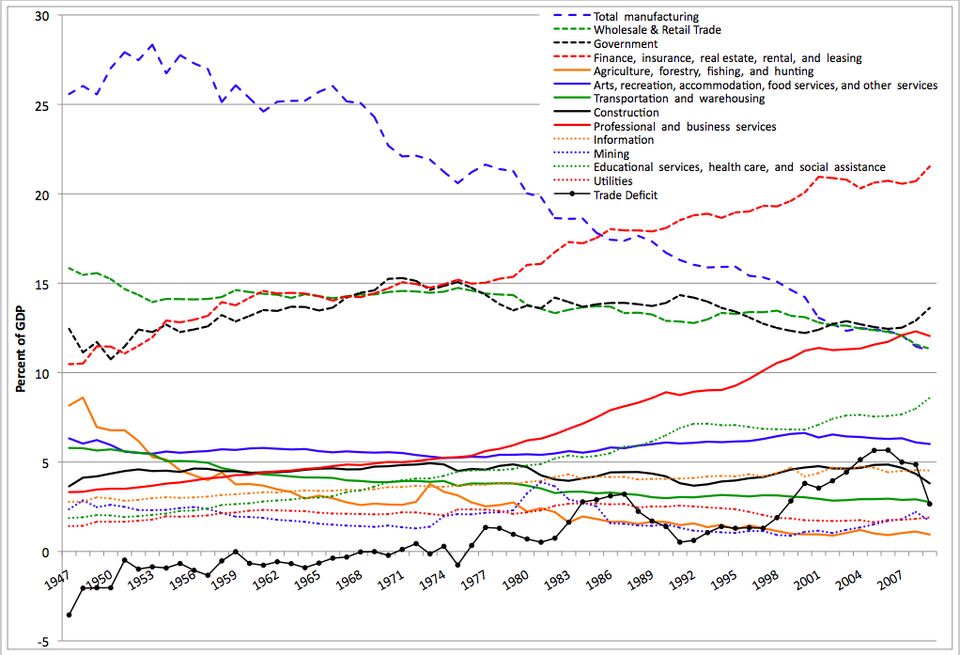

This chart illustrates the steady rise of the service sector and the long-term decline of the industrial share of GDP from 1947 to 2009. The visual trend supports the text’s explanation of how service industries became the dominant force in the late twentieth-century U.S. economy. The agricultural share is included as additional context beyond the syllabus but helps demonstrate the broader structural shift in economic activity. Source.

While some service-sector jobs—such as engineering, finance, or software development—offered high wages and opportunities for professional advancement, many others were low-wage, part-time, or unstable, especially in retail, food service, and hospitality. This contributed to broader concerns about economic inequality and declining job security for working-class Americans.

Normal sentence: The shift in economic structure produced new expectations for education and workforce training, as service-sector positions increasingly required interpersonal, technological, or specialized skills.

Declining Unions and Shifting Labor Relations

The decline of manufacturing directly weakened labor unions, long strongest in industrial workplaces. Union membership had peaked in the mid-twentieth century, but after 1980 it fell sharply due to structural changes and political developments.

Labor union: An organized association of workers formed to protect and advance their collective interests in wages, benefits, and working conditions.

As factories closed or relocated, unions lost major strongholds. Service-sector jobs were more difficult to organize because they were often dispersed, part-time, or located in industries—such as retail or fast food—historically resistant to collective bargaining.

Several political and legal developments further constrained union influence:

Federal labor policy under conservative administrations supported deregulation and employer flexibility, making unionization campaigns more difficult.

Right-to-work laws, adopted increasingly by states, limited unions’ ability to collect dues and maintain membership.

Judicial decisions narrowed the scope of permissible union activity or strengthened employers’ rights in disputes.

As a result, unions represented a shrinking share of the workforce, weakening their capacity to shape national debates over wage standards, workplace protections, and social welfare policy.

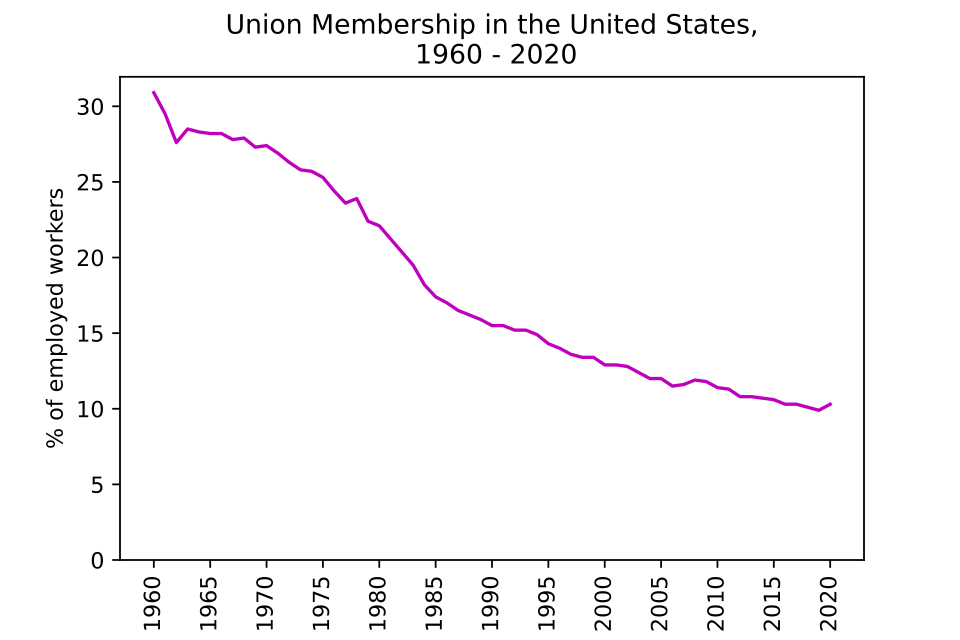

This chart shows the steady decline in the share of U.S. workers belonging to unions from 1960 to 2020, with sharp drops after the early 1980s. The trend aligns with the text’s explanation of diminishing labor power amid economic restructuring and the rise of service-sector employment. The graph continues past the AP period, but the extended timeline reinforces the persistence of declining unionization. Source.

Economic, Regional, and Social Consequences

Deindustrialization, the rise of services, and declining unions collectively reshaped American society. Their effects varied widely across different geographic regions, racial and ethnic groups, and educational levels.

Regional Impacts

The Rust Belt experienced population loss, urban decline, and fiscal crisis as factories shuttered.

The Sun Belt benefited from new service and technology hubs, attracting migrants and investment.

Suburban and exurban areas grew as economic activity dispersed away from traditional industrial centers.

Social and Political Impacts

Workers displaced from manufacturing often faced downward mobility or retraining challenges.

Declining union power reduced organized labor’s political influence within the Democratic Party.

Expanding high-skill service industries contributed to the rise of a professional class with distinct political and cultural outlooks.

Growing wage inequality fueled debates over the minimum wage, trade policy, and the role of government in supporting workers.

Transformation of Work and Identity

Changes in work patterns after 1980 altered Americans’ sense of economic opportunity and personal identity. Industrial labor had once provided stable careers linked to community and family life. Service-sector employment, by contrast, often involved flexible schedules, temporary contracts, and shifting employer expectations. These conditions influenced attitudes toward social policy, economic security, and the future of the U.S. workforce.

FAQ

Deindustrialisation disproportionately affected older, less formally educated workers who had built long-term careers in manufacturing. These workers often faced challenges retraining for emerging service-sector roles.

African American industrial workers in cities such as Detroit, Cleveland, and Pittsburgh experienced particularly acute job losses because they were heavily represented in auto and steel plants.

Immigrant workers were affected unevenly: some lost manufacturing roles, while others moved into expanding service industries such as food service and healthcare.

Service-sector workplaces tend to be decentralised, smaller, and more transient, making collective organisation difficult.

Employers in retail and hospitality often relied on part-time or temporary labour, which reduces opportunities for coordinated worker mobilisation.

Additionally, many service-sector employers adopted anti-union strategies, including hiring consultants or promoting “open shop” environments, which further impeded union formation.

Cities facing major factory closures often experienced population decline, leading to abandoned homes, reduced business activity, and shrinking municipal budgets.

Former industrial districts frequently fell into disuse, with warehouses and plants left vacant or demolished.

Some cities later pursued redevelopment through green spaces, cultural districts, or technology hubs, though outcomes varied widely.

Growth occurred both in high-skilled and low-skilled areas.

High-skilled roles included finance, insurance, engineering, software development, and telecommunications.

Low-wage jobs expanded rapidly in hospitality, retail, food service, home healthcare, and custodial work, contributing to a widening gap within the service sector itself.

Lower union density reduced upward pressure on wages across the broader labour market, since unions historically helped set industry standards even in non-union workplaces.

The weakening of collective bargaining made it more difficult for workers to secure benefits such as employer-funded healthcare or pensions.

In many regions, the loss of union influence contributed to wage stagnation and rising income inequality during the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain one major cause of the decline in manufacturing employment in the United States after 1980.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark: Identifies a valid cause (e.g., automation, global competition, offshoring of production).

2 marks: Provides a clear explanation of how the identified cause contributed to declining manufacturing employment.

3 marks: Shows specific understanding by linking the cause to broader economic or structural shifts (e.g., globalisation leading to factory relocation to lower-wage countries, or automation reducing labour demand despite rising productivity).

(4–6 marks)

Evaluate the extent to which the rise of the service economy after 1980 reshaped the experiences of American workers.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

4 marks: Provides a general explanation of how the service economy grew and identifies at least one way it affected American workers (e.g., rise of low-wage service jobs, growth of high-skilled professions).

5 marks: Offers a more developed evaluation, addressing both positive and negative impacts (e.g., new professional opportunities versus declining job security and wage stagnation).

6 marks: Presents a well-argued, balanced assessment with specific historical detail and clear reasoning about the extent of change (e.g., service-sector predominance altering work patterns, weakening unions, widening inequality).