AP Syllabus focus:

‘Real wages stagnated for many working- and middle-class Americans, even as economic inequality increased in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.’

Wage stagnation and rising inequality became defining economic trends after 1980, reshaping Americans’ expectations about opportunity, work, and class mobility amid rapid technological change and global economic restructuring.

Wage Stagnation in the Late 20th and Early 21st Centuries

Wage stagnation describes the long-term failure of real wages—wages adjusted for inflation—to rise meaningfully for large segments of workers. This issue persisted across multiple business cycles and presidential administrations, making it a widespread structural challenge rather than a temporary economic downturn.

Real Wages: Wages adjusted to reflect the effects of inflation, measuring purchasing power rather than nominal earnings.

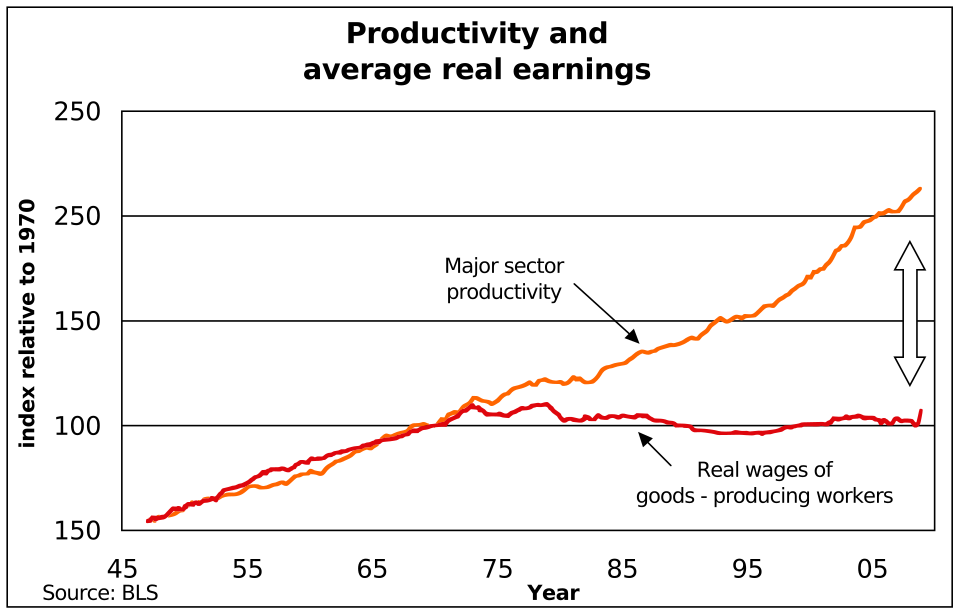

Beginning in the 1970s and intensifying after 1980, many working- and middle-class Americans experienced flat or declining real wage growth. Despite increases in labor productivity, workers did not share proportionally in the economic gains.

This chart compares productivity in major U.S. goods-producing industries with the average real wages of workers from 1947 to 2008. The widening gap highlights how output per worker rose much faster than pay, a key driver of wage stagnation for working- and middle-class Americans. The early decades provide historical context, while the post-1980 divergence is especially important for understanding economic change in Period 9. Source.

Several forces converged to limit wage growth:

Globalization and international competition increased pressure on U.S. manufacturing wages.

Automation and digital technologies rewarded highly skilled workers while reducing demand for lower-skilled labor.

Declining union strength weakened collective bargaining, reducing workers’ ability to negotiate higher wages and benefits.

Shifts toward service-sector employment, often in lower-paying industries, constrained overall income growth.

These conditions generated persistent economic frustration, influencing political discourse and public attitudes toward government policy.

Causes of Wage Stagnation

Wage stagnation cannot be attributed to a single factor; instead, it emerged from overlapping economic transformations that reshaped the U.S. labor market.

Globalization and the Decline of Manufacturing

After 1980, the U.S. economy underwent a major transition as manufacturing jobs moved abroad or became increasingly automated. American firms faced competition from nations with lower labor costs, contributing to:

Plant closures and offshoring.

Reduced bargaining power for industrial workers.

A shift toward service-sector employment, where wages were often lower and benefits less stable.

This contributed to regional disparities, especially in the Rust Belt, where many communities experienced long-term job loss and economic decline.

Technological Change and Skill-Based Inequality

The rapid growth of computing, robotics, and digital communication technologies favored workers with technical or managerial expertise. As a result:

High-skilled, high-wage jobs expanded in fields such as technology, finance, and engineering.

Routine manual and clerical tasks were increasingly automated or outsourced.

Educational attainment became more closely tied to lifetime income, deepening socioeconomic divides.

Workers without college degrees bore the brunt of these changes, contributing to downward mobility for many middle-class families.

Declining Union Membership and Worker Power

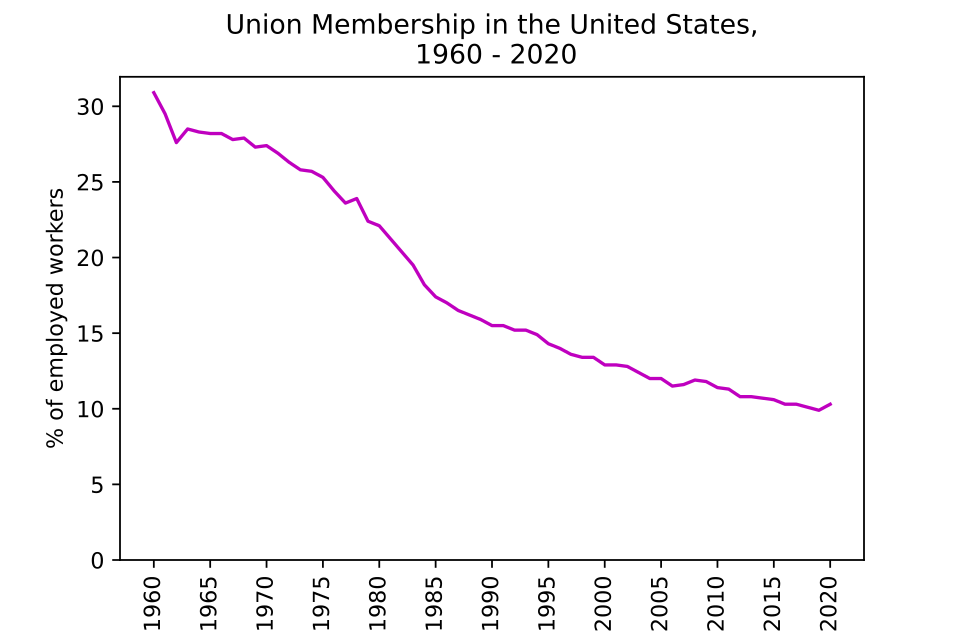

Unions historically played a major role in raising wages, improving working conditions, and negotiating benefits. After 1980, union membership declined sharply due to:

Shifts in labor laws and political attitudes toward regulation.

The geographic shift of jobs to states with weaker labor protections.

Employer strategies aimed at limiting collective bargaining.

The result was a labor market where fewer workers had access to the protections and wage gains unions once provided.

This graph shows the percentage of employed workers in the United States who belonged to labor unions from 1960 to 2020. The steady decline after the late 1970s illustrates the weakening of union power that reduced many workers’ leverage to secure higher wages and benefits. The chart extends beyond the APUSH period to 2020, but the post-1980 slide is especially important for understanding wage stagnation and inequality in Period 9. Source.

Rising Economic Inequality

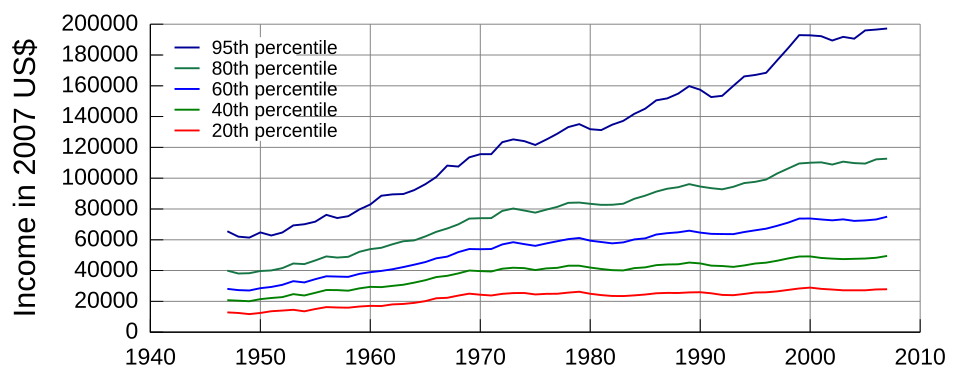

While wages stagnated for many households, income and wealth inequality surged.

Economic Inequality: The uneven distribution of income and wealth across a population, often measured by differences between top earners and average workers.

This graph tracks the income received by different segments of U.S. families—from the lowest fifth up to the top 5 percent—between 1947 and 2007, adjusted to 2007 dollars. The lines for upper-income groups rise much more steeply than those for lower and middle fifths, illustrating the growth of income inequality that accompanied wage stagnation in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Earlier decades provide background, but the post-1980 divergence is especially important for understanding Period 9. Source.

Several developments accelerated this divergence:

Executive compensation grew rapidly relative to average worker pay.

Financialization—the growing importance of financial markets and investment income—disproportionately benefited wealthier households.

Tax policy changes, including reductions in top marginal income tax rates and capital gains taxes, increased the after-tax income of high earners.

Wealth concentration, driven by real estate, stocks, and business ownership, produced inherited advantages across generations.

These trends reshaped debates about fairness, opportunity, and the meaning of the American Dream.

Social and Political Consequences of Inequality

The rise in inequality had far-reaching effects on American society and political culture.

Shifts in Public Attitudes and Political Alignment

Many Americans questioned whether the economic system remained fair or accessible. This contributed to:

Increased polarization over tax policy and government spending.

Support for political movements promising economic reform or protectionist trade policies.

Growing distrust in institutions perceived as benefiting elites.

Economic frustration became a powerful force across the political spectrum.

Impacts on Mobility, Education, and Community Stability

The widening gap between rich and poor influenced everyday life:

Intergenerational mobility decreased, especially for children in low-income households.

Public education systems in lower-income areas faced funding challenges.

Economic inequality contributed to geographic divergence, with affluent and struggling regions growing further apart.

These changes produced long-term cultural and demographic consequences that shaped national debates well into the 21st century.

Federal Policy Debates and Responses

Policymakers proposed differing solutions to wage stagnation and inequality. Efforts ranged from expanding the social safety net to deregulating markets in hopes of stimulating growth. Common areas of debate included:

Minimum wage increases.

Tax reform and redistribution.

Trade policy and job retraining programs.

Support for unions and collective bargaining rights.

Incentives to promote technological innovation while protecting displaced workers.

Though proposals varied, the underlying issue—how to restore economic opportunity—remained central to political discussions in the early 21st century.

FAQ

Corporations increasingly prioritised shareholder returns over employee wage growth, a shift reinforced by the rise of performance-based executive pay and pressure from institutional investors.

This focus encouraged cost-cutting strategies such as outsourcing, automation, and wage suppression, particularly in labour-intensive sectors.

It also redirected corporate profits toward dividends and share buybacks rather than worker compensation or long-term reinvestment.

The move from defined-benefit pensions to defined-contribution plans reduced long-term financial stability for many workers, especially those in middle-income occupations.

Employers transferred more investment risk to employees, meaning retirement income depended heavily on individual contributions and market performance.

This shift contributed to broader perceptions of economic precarity, even among workers whose nominal wages had not fallen.

Technological change raised the premium on advanced skills while reducing demand for routine manual and clerical roles.

Workers without higher education were more likely to be concentrated in sectors facing offshoring, automation, or low-wage service work.

Limited access to retraining programmes and rising education costs further restricted mobility into higher-paying occupations.

Areas dependent on manufacturing, such as parts of the Midwest and Northeast, faced long-term decline as factories closed or automated.

In contrast, regions anchored by technology, finance, or specialised services—particularly the West Coast and major metropolitan areas—experienced rapid income growth.

These contrasting trajectories deepened regional inequalities in wages, housing wealth, and opportunities for advancement.

To maintain living standards amid stagnant earnings, many households relied more heavily on credit cards, mortgages, and student loans.

Rising debt levels left families more vulnerable during economic downturns, as loan repayments consumed a greater share of disposable income.

This reliance on borrowing masked wage stagnation in the short term but contributed to long-term financial strain, especially during the 2008 financial crisis.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify one major factor that contributed to wage stagnation for many working- and middle-class Americans after 1980, and briefly explain how it affected wage growth.

Mark scheme

1 mark for correctly identifying a relevant factor (e.g., globalisation, automation, decline of unions, shift to service-sector employment).

1 mark for a clear explanation of how the factor limited wage growth (e.g., increased competition lowered manufacturing wages, automation reduced demand for routine labour).

1 mark for demonstrating specific contextual understanding related to the post-1980 period (e.g., offshoring of industrial jobs; weakening collective bargaining rights).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Explain how rising economic inequality in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries reshaped political attitudes and debates in the United States.

Mark scheme

1–2 marks for describing the trend of rising economic inequality (e.g., widening income gaps, disproportionate gains for high earners).

1–2 marks for explaining at least one political impact (e.g., greater polarisation over tax policy; increased support for reform movements; distrust of political and economic institutions).

1–2 marks for using historically specific evidence from the post-1980 period to support the explanation (e.g., debates over minimum wage, deregulation, trade policy, union rights).

Full marks require coherent explanation, clear linkage between inequality and political consequences, and accurate contextual detail.