AQA Specification focus:

‘The determinants of savings The difference between saving and investment.’

This section explains the role of saving and investment in the macroeconomy, highlighting their differences and the determinants influencing both, crucial for understanding aggregate demand dynamics.

Saving vs Investment

Defining Saving

Saving: The portion of disposable income not spent on consumption but set aside, often in financial institutions or assets.

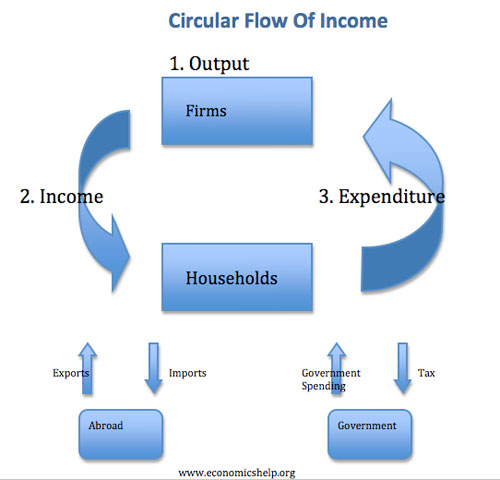

In the circular flow of income, saving represents a withdrawal from spending, reducing immediate aggregate demand. However, savings also provide the funds for investment, linking households and firms.

This diagram depicts the circular flow of income, demonstrating how money circulates between households and firms. It shows the balance between injections and withdrawals, emphasizing the equilibrium condition where planned saving equals planned investment. Source

Defining Investment

Investment: Expenditure by firms on capital goods such as machinery, buildings, or technology, intended to increase productive capacity in the future.

Investment represents an injection into the economy, stimulating demand and contributing to long-term growth by enhancing productive efficiency.

Although related, saving and investment are conceptually distinct. Saving refers to income not spent, while investment refers to the creation of new productive assets. In a closed economy without government or foreign trade, savings and investment must be equal in equilibrium, though in practice imbalances often occur.

This illustration contrasts saving and investment in economic terms. It highlights that saving involves setting aside income, often in financial institutions, while investment pertains to spending on capital goods to enhance future productive capacity. Source

Determinants of Saving

Several factors influence the level of household and business saving:

Income levels: Higher real disposable income generally leads to greater absolute saving, though the proportion saved depends on preferences.

Interest rates: Rising interest rates increase the reward for saving, incentivising households to defer consumption.

Consumer confidence: If households expect future downturns, they may raise precautionary saving. Conversely, optimism may reduce saving.

Wealth and assets: Rising house or share prices may reduce saving due to the wealth effect, as people feel richer and spend more.

Government policies: Tax incentives such as ISAs in the UK encourage saving; conversely, high direct taxation reduces disposable income and lowers saving.

Cultural factors and social norms: Attitudes towards thrift and borrowing vary internationally, shaping saving rates.

Marginal Propensity to Save

Marginal Propensity to Save (MPS): The proportion of an additional unit of disposable income that households save rather than spend.

A higher MPS dampens the multiplier effect, as less of an income injection circulates through the economy.

Determinants of Investment

Investment decisions are influenced by multiple economic conditions and expectations:

Interest rates: Lower borrowing costs make capital investment more affordable, while high rates deter it.

Business confidence: Firms invest more when they expect rising demand and profitability, often captured by the Keynesian concept of ‘animal spirits’.

Government policy: Subsidies, tax allowances, or infrastructure spending can encourage private sector investment.

Technological advances: Innovations stimulate investment in new capital to maintain competitiveness.

Cost of capital goods: Cheaper equipment encourages more investment; rising input costs may deter it.

Global economic conditions: Open economies are affected by foreign demand and global financial markets, influencing both inward and outward investment.

Exchange rates: A strong currency may discourage export-oriented investment, while a weaker currency may encourage it.

The Accelerator Principle

Accelerator Principle: The theory that a change in the level of output or demand can cause a proportionally larger change in the level of investment.

When demand grows, firms expand capacity, often leading to significant rises in investment; conversely, falling demand leads to sharp investment declines.

Relationship Between Saving and Investment

Though saving and investment are separate activities, they are closely linked within the macroeconomy:

Savings provide funds for investment: In financial markets, households’ savings are channelled into loans or capital for businesses.

Equilibrium condition: In macroeconomic theory, for national income to be stable, planned saving must equal planned investment.

Imbalances: If planned saving exceeds investment, aggregate demand falls, reducing output and employment. If investment exceeds saving, excessive demand may fuel inflation.

Equation Linking Saving and Investment

National Income (Y) = Consumption (C) + Investment (I)

Savings (S) = National Income (Y) – Consumption (C)

Therefore, in equilibrium: S = I

Y = C + I

This framework highlights the dependence of economic stability on the interaction between saving behaviour and investment decisions.

Importance in the Circular Flow

Saving acts as a withdrawal from the circular flow of income, reducing short-term spending.

Investment acts as an injection, stimulating demand and supporting economic growth.

Shifts in saving or investment behaviour can therefore impact national income, employment, and long-run productive capacity.

Together, the determinants of saving and investment shape the stability and growth of the macroeconomy, making their distinction and analysis essential to understanding aggregate demand.

FAQ

The average propensity to save (APS) measures the proportion of total income that is saved, while the marginal propensity to save (MPS) measures the proportion of additional income that is saved.

APS = Total Saving ÷ Total Income

MPS = Change in Saving ÷ Change in Income

MPS is particularly important in explaining the size of the multiplier, while APS gives a general picture of saving behaviour at a given income level.

While saving provides funds for investment, if households save too much relative to consumption, aggregate demand falls.

This can lead to:

Lower output and employment in the short run.

Reduced incentives for firms to invest.

A possible paradox of thrift, where attempts to save more collectively reduce overall income, making actual saving lower.

The life-cycle hypothesis suggests individuals plan consumption and saving across their lifetime.

During youth, saving is low or negative (borrowing for education, housing).

In working years, saving rises as income increases.

In retirement, individuals dissave, using accumulated savings.

This perspective helps explain why aggregate saving levels can vary depending on the age structure of the population.

Financial institutions act as intermediaries, channelling savings into investment.

Households deposit savings into banks or investment funds.

Banks lend these funds to businesses for capital projects.

Efficient financial markets reduce risks and transaction costs, encouraging both saving and investment.

Weak financial systems can disrupt this link, reducing the effectiveness of saving in supporting productive investment.

Cultural norms significantly affect the propensity to save.

For example:

In some East Asian economies, saving rates are traditionally high due to strong cultural emphasis on thrift and precautionary saving.

In contrast, Anglo-American economies often exhibit lower saving rates, influenced by greater reliance on credit and consumerism.

These differences help explain variations in domestic investment financing and reliance on foreign capital across nations.

Practice Questions

Define the term investment in the context of the macroeconomy. (2 marks)

1 mark for stating that investment is spending by firms on capital goods (e.g., machinery, buildings, technology).

1 mark for recognising the purpose is to increase future productive capacity/output.

Explain two factors that may influence the level of household saving in an economy. (6 marks)

Up to 3 marks per factor (maximum 6):

Identification of a factor (1 mark) e.g., income levels, interest rates, consumer confidence, government policies.

Explanation of how the factor affects saving behaviour (1–2 marks).

Example: Higher interest rates (1 mark) make saving more rewarding, so households may save more rather than spend (2 marks).

Example: Rising incomes (1 mark) increase the absolute amount that can be saved, though the proportion may vary (2 marks).