AQA Specification focus:

‘The price level and production costs are the main determinants of the short-run AS.’

Introduction

In the short run, aggregate supply (SRAS) reflects the relationship between total output and the price level, shaped heavily by firms’ production costs and market conditions.

Short-Run Aggregate Supply (SRAS)

What SRAS Represents

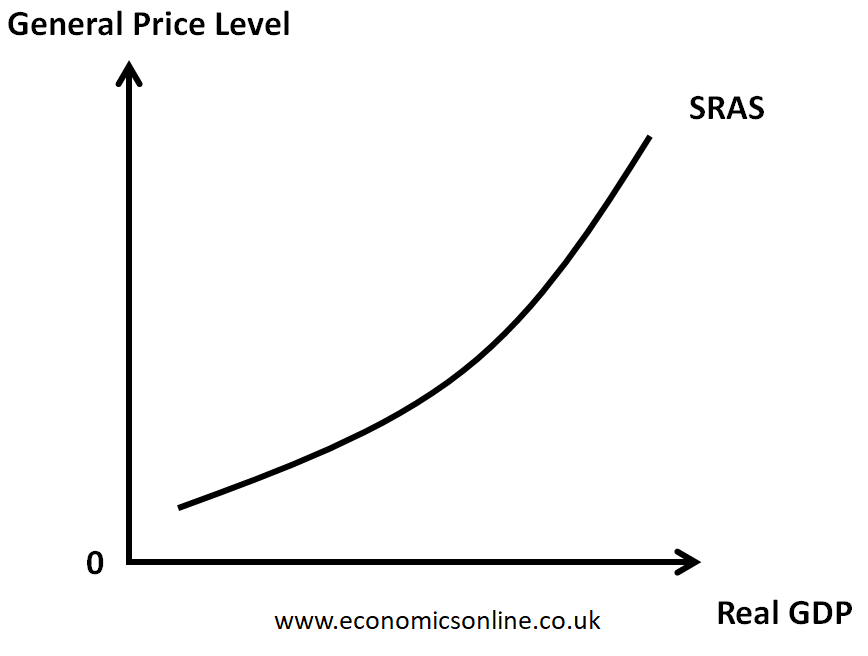

SRAS shows the total quantity of goods and services that firms in an economy are willing and able to supply in the short run at different overall price levels. It assumes that at least one factor of production, typically capital, is fixed, while other inputs such as labour or raw materials can vary.

Short-Run Aggregate Supply (SRAS): The total output that firms are willing and able to produce at different price levels, given that at least one factor of production is fixed.

The Role of the Price Level

Profit Incentives

The price level is crucial in determining SRAS because it directly affects firms’ profitability. If the general price level rises, the revenue firms receive from selling goods and services increases, provided nominal wages and costs remain unchanged in the short run. This motivates firms to expand production.

A higher price level → higher profit margins → increased willingness to supply.

A lower price level → squeezed profit margins → reduced willingness to supply.

This relationship underpins the upward-sloping SRAS curve.

Production Costs as Determinants of SRAS

Key Cost Components

Production costs strongly influence SRAS. When costs increase, it becomes more expensive for firms to produce, shifting the SRAS curve leftwards. When costs fall, firms can supply more at any given price level, shifting SRAS rightwards.

Important costs include:

Wage rates: Labour is a major cost for most firms. Rising wages reduce profitability unless matched by higher productivity.

Raw material prices: Increases in the cost of oil, metals, or food inputs raise firms’ costs across the economy.

Business taxation: Higher indirect taxes (e.g., VAT, excise duties) increase firms’ costs, while subsidies lower them.

Productivity changes: Higher productivity reduces average costs, making it easier for firms to increase supply.

Cost Shock: A sudden and significant change in firms’ production costs, often caused by wage rises, raw material price fluctuations, or changes in taxation.

The Interaction of Price Level and Costs

Short-Run Equilibrium Output

The actual output in the economy depends on both the price level and the current cost conditions faced by firms.

If price levels rise while costs remain stable, SRAS expands.

If costs increase sharply (e.g., an oil price spike), the SRAS curve shifts left, reducing output even if price levels rise.

This dynamic highlights why both demand-side and supply-side factors must be considered in analysing economic performance.

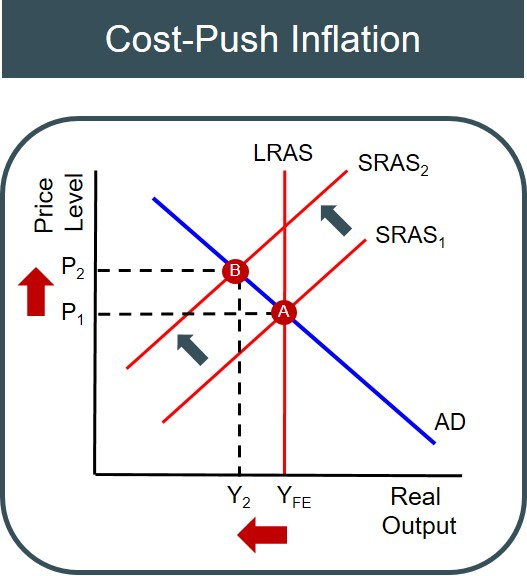

When production costs rise across the economy, firms’ profit margins fall at existing price levels. This forces a leftward shift of the SRAS curve.

This diagram demonstrates how cost-push inflation, caused by rising production costs, shifts the SRAS curve leftward, leading to higher price levels and reduced output. Source

Why SRAS is Upward Sloping

Nominal Wage Rigidity

In the short run, nominal wages are often fixed due to labour contracts or institutional arrangements. Because wages do not immediately adjust to inflation, a rise in the general price level increases firms’ real revenues relative to wage costs.

Nominal Wage Rigidity: The tendency for wages to remain fixed in the short run due to contracts or institutional constraints, even when price levels change.

This explains why higher price levels encourage more output in the short run, but not indefinitely, since eventually wages and costs adjust.

This diagram illustrates the short-run aggregate supply curve, emphasising the role of sticky wages in causing the curve to slope upward, as wages do not immediately adjust to changes in the price level. Source

Cost-Push Pressures

How Rising Costs Reduce SRAS

When production costs rise across the economy, firms’ profit margins fall at existing price levels. This forces a leftward shift of the SRAS curve.

Key examples of cost-push pressures:

Oil price shocks (raising transport and energy costs).

Rising global commodity prices.

Increases in indirect taxes.

These effects are distinct from demand-pull inflation, which comes from rising aggregate demand. Cost-push inflation originates from the supply side.

Linking SRAS to Inflation and Output

Inflationary Effects

Shifts in SRAS are central to understanding inflation dynamics. For example:

A rightward shift (e.g., lower wages, cheaper inputs) reduces cost pressures, lowering inflationary pressure while raising output.

A leftward shift (e.g., wage spikes, higher oil prices) creates cost-push inflation, raising the price level while reducing output.

Cost-Push Inflation: Inflation caused by an increase in production costs that shifts SRAS leftward, raising the price level while reducing real output.

Factors that Keep SRAS Stable in the Short Run

Sticky Prices and Contracts

SRAS is influenced by the relative inflexibility of prices and costs in the short run. Important stabilising factors include:

Long-term labour contracts, which prevent immediate wage adjustments.

Input supply contracts fixing raw material prices temporarily.

Government subsidies cushioning cost changes in key industries.

These rigidities allow the price level to be the key driver of output adjustments in the short run, making SRAS relatively predictable within a given timeframe.

FAQ

The SRAS curve slopes upward because firms can expand output when prices rise, given that some costs (like wages) are sticky in the short run.

By contrast, the LRAS curve is vertical, reflecting that in the long run, output is determined by productive capacity, not price levels.

Wages often make up the largest share of firms’ costs. If wages increase without corresponding productivity gains, average costs rise significantly.

This makes wage agreements, collective bargaining, and minimum wage policies key factors influencing shifts in SRAS.

Yes, SRAS can shift rightwards when production costs fall, making it cheaper for firms to supply goods.

Examples include:

Wage reductions

Lower raw material prices

Cuts in business taxation

Short-term productivity improvements

Supply contracts often lock in wages or input prices for a fixed period, preventing immediate cost fluctuations.

This makes SRAS less volatile in the short term, as firms are shielded from sudden shocks like temporary spikes in commodity prices.

Cost shocks originate from the supply side, such as rising wages or higher energy costs, and shift SRAS left.

Demand shocks, by contrast, affect aggregate demand and cause movements along the SRAS curve rather than shifting it directly.

Practice Questions

Explain why the short-run aggregate supply (SRAS) curve slopes upwards. (3 marks)

1 mark for identifying that higher price levels increase firms’ willingness to produce.

1 mark for linking this to fixed or slow-to-adjust costs (e.g., nominal wage rigidity).

1 mark for recognising that higher prices increase profit margins, leading to more output supplied.

Analyse how an increase in wages might affect the short-run aggregate supply (SRAS) curve. (6 marks)

1 mark for recognising that wages are a major component of firms’ production costs.

1 mark for explaining that higher wages raise average costs of production.

1 mark for stating that this reduces profitability at existing price levels.

1 mark for noting that SRAS shifts leftward as firms supply less at each price level.

1 mark for identifying the potential outcome of higher price levels (cost-push inflation).

1 mark for recognising reduced output and potential negative effects on economic growth.