AQA Specification focus:

‘Changes in costs, such as: money wage rates, raw material prices, business taxation and productivity, will shift the short-run AS curve.’

Understanding how cost shocks influence the short-run aggregate supply (SRAS) is essential for analysing fluctuations in output, employment, and prices within an economy in the short term.

The Nature of Short-Run Aggregate Supply (SRAS)

The short-run aggregate supply (SRAS) curve shows the relationship between the overall price level and the quantity of real output firms are willing to produce in the short run. In this period, some factors of production (such as capital stock) are fixed, but variable inputs (like labour and raw materials) can change.

The SRAS curve is generally upward-sloping because, as the price level rises, firms are incentivised to produce more due to higher profit margins, assuming production costs remain constant. However, when cost shocks occur, they shift the entire SRAS curve rather than causing movement along it.

Cost Shocks: Definition and Impact

Cost shock: An unexpected change in production costs that affects firms across the economy, causing the short-run aggregate supply (SRAS) curve to shift.

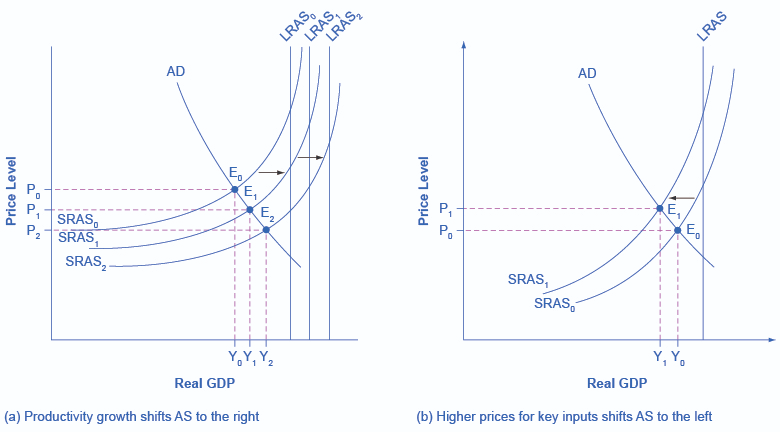

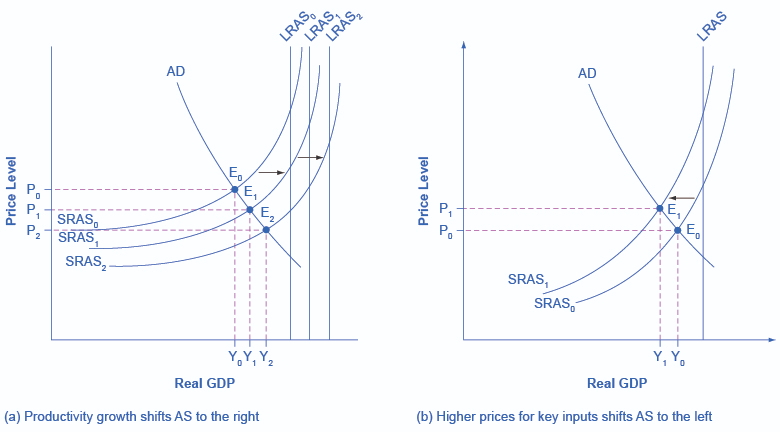

A cost shock directly alters the profitability of producing goods and services. If production costs rise, firms reduce output at every price level, shifting SRAS leftward. Conversely, a fall in production costs shifts SRAS rightward, indicating greater willingness to produce at each price level.

Types of Cost Shocks That Shift SRAS

Money Wage Rates

Wage costs are the largest component of total business costs. Changes in money wage rates (the cash wages paid to workers, unadjusted for inflation) significantly influence SRAS.

Rising wages increase unit labour costs, shifting SRAS leftward.

Falling wages reduce costs, shifting SRAS rightward.

Money wage rate: The nominal amount of pay received by workers before adjusting for inflation.

Wage changes may result from collective bargaining, minimum wage legislation, or labour shortages in key industries.

This graph demonstrates the leftward shift of the short-run aggregate supply (SRAS) curve in response to increased input prices. As production costs rise, firms reduce output at each price level, leading to higher overall prices and potential inflationary pressures. Source

Raw Material Prices

Fluctuations in the cost of raw materials, such as oil, metals, or agricultural products, can cause substantial shifts in SRAS.

Increases in oil prices, for example, raise transport and energy costs economy-wide, shifting SRAS leftward.

Cheaper access to materials, due to global oversupply or trade deals, shifts SRAS rightward.

These shocks are often linked to global commodity markets and geopolitical developments.

The diagram shows the SRAS curve shifting leftward due to a significant increase in oil prices. As oil is a critical input for many industries, its price hike raises production costs across the economy, leading to reduced output and higher prices. Source

Business Taxation

Changes in business taxation directly affect firms’ costs of production.

Higher corporation tax or indirect taxes (e.g. VAT, excise duties) increase production costs, reducing SRAS.

Reductions in such taxes lower costs, enabling greater output at each price level.

It is important to distinguish between taxes on profits and taxes on production inputs, both of which can impact the SRAS curve.

Productivity

Productivity refers to output per unit of input. Improvements in productivity lower average costs, enabling more output to be produced with the same resources.

Increases in productivity shift SRAS rightward.

Decreases in productivity, perhaps due to outdated technology or inefficiencies, shift SRAS leftward.

Productivity: The efficiency of production, measured as output per unit of input (such as labour or capital).

Productivity is influenced by investment in technology, training, management practices, and infrastructure.

The Mechanism of SRAS Shifts

When cost shocks occur, the adjustment process in the macroeconomy can be summarised as:

Rising costs → SRAS shifts left → higher price level (inflationary pressure) + lower real output (potential unemployment).

Falling costs → SRAS shifts right → lower price level (deflationary pressure) + higher real output (potential employment gains).

This mechanism illustrates how supply-side conditions contribute to macroeconomic stability or volatility.

Distinguishing SRAS Shifts from Movements Along SRAS

It is crucial to differentiate between:

Movements along SRAS: Caused by changes in the price level with costs unchanged.

Shifts of SRAS: Caused by changes in production costs (cost shocks), independent of the price level.

This distinction prevents misinterpretation when analysing economic data and drawing policy conclusions.

Short-Term vs Long-Term Considerations

Cost shocks primarily influence the short run because wages, raw material prices, and tax structures can change quickly. In the long run, other factors—such as investment in technology or structural reforms—become more significant in determining aggregate supply. However, repeated or persistent cost shocks may reduce long-term competitiveness and investment.

Examples of Real-World Cost Shocks

Bullet points help highlight key cases of SRAS shifts in recent history:

Oil price spikes (e.g., during conflicts in the Middle East) leading to global SRAS contractions.

Minimum wage rises implemented across advanced economies, raising labour costs in low-skilled industries.

Tax policy changes, such as increases in carbon taxes, affecting firms reliant on fossil fuels.

Pandemic-related productivity losses due to supply chain disruptions and restrictions on workplace activity.

Each of these examples shows how quickly SRAS can adjust in response to cost shocks.

Policy Responses to Cost Shocks

Governments and central banks may respond to adverse cost shocks in different ways:

Monetary policy (e.g., lowering interest rates) to stimulate demand, though this may worsen inflation in cases of negative supply shocks.

Fiscal policy (e.g., subsidies or tax cuts) to offset rising costs for businesses.

Supply-side policies (e.g., training schemes, deregulation) to improve productivity and resilience against future shocks.

These measures illustrate the trade-offs policymakers face between controlling inflation and supporting growth.

FAQ

Cost shocks affect the short-run aggregate supply (SRAS) by altering firms’ production costs, whereas demand shocks shift the aggregate demand (AD) curve.

Cost shocks typically cause both output and price level changes, often creating stagflation (falling output with rising prices).

Demand shocks primarily change the level of spending in the economy, influencing output and prices differently depending on conditions.

Oil is a key input for transport, manufacturing, and energy. A change in oil prices quickly affects the costs of many industries, creating widespread supply effects.

Rising oil prices increase production and transport costs, shifting SRAS leftward.

Falling oil prices lower these costs, shifting SRAS rightward.

Because oil is globally traded and essential, its price volatility provides a clear example of how cost shocks ripple through an economy.

Yes, positive cost shocks happen when production costs fall unexpectedly.

Examples include:

A sudden fall in global commodity prices.

A technological breakthrough that reduces input costs.

Government subsidies lowering the effective costs of production.

These shocks shift SRAS to the right, increasing output and reducing inflationary pressure.

Large wage rises in key sectors, like healthcare or transport, can spread through the economy.

Higher wages raise demand for goods and services, encouraging further wage pressures.

Other industries may need to raise wages to retain workers.

Firms pass on higher labour costs to consumers, creating a broader leftward SRAS shift.

Thus, sectoral wage changes can trigger economy-wide supply effects.

Expectations influence whether cost shocks cause temporary or lasting effects.

If firms expect costs to fall back quickly, they may absorb the shock in profits.

If they expect costs to remain high, they pass costs onto consumers, shifting SRAS left.

Persistent expectations of higher costs can trigger wage-price spirals.

This shows how psychology and forward-looking behaviour matter in supply-side economics.

Practice Questions

Explain one way in which an increase in money wage rates can affect the short-run aggregate supply (SRAS) curve. (3 marks)

1 mark for identifying that higher money wages increase firms’ costs of production.

1 mark for stating that higher costs reduce profitability/output at each price level.

1 mark for explaining that this shifts the SRAS curve to the left.

Discuss how changes in the prices of raw materials, such as oil, can affect the short-run aggregate supply (SRAS) curve and the wider economy. (6 marks)

Up to 2 marks for explaining that higher raw material prices raise firms’ production costs.

Up to 2 marks for explaining that this causes the SRAS curve to shift leftward (reduced output, higher price level).

Up to 2 marks for application/analysis of the wider economic effects, e.g. inflationary pressures, reduced economic growth, potential increase in unemployment.