AQA Specification focus:

‘Students should understand that long-run economic growth occurs when the productive capacity of the economy is increasing and is a term used to refer to the trend rate of growth of real national output in an economy over time.’

Economic growth over the long run reflects sustained improvements in productive capacity. It highlights structural changes in the economy and indicates the trend rate of expansion.

Understanding Long-Run Economic Growth

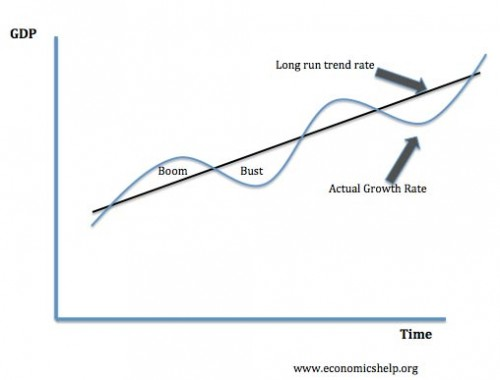

Long-run economic growth refers to a sustained increase in an economy’s productive capacity over time. Unlike short-run fluctuations driven by changes in aggregate demand, long-run growth focuses on structural improvements in output potential. It is measured by the trend rate of growth, which represents the average growth path of real national output when the economy is operating at full productive potential.

Long-Run Economic Growth: An increase in the productive capacity of the economy over time, enabling higher levels of output and living standards.

This perspective removes temporary distortions caused by booms or recessions and highlights the underlying pace at which the economy can grow sustainably.

The Trend Rate of Growth

The trend rate of growth is the long-term average rate at which an economy can expand without generating inflationary pressures. It reflects the capacity of the supply side rather than temporary demand shifts.

Trend Rate of Growth: The average rate at which real national output can grow sustainably over time, consistent with stable inflation.

In the UK, for example, the trend rate has historically been estimated around 2–2.5% per year, though this varies depending on productivity, labour force growth, and global conditions.

Determinants of Long-Run Growth

Several supply-side factors determine an economy’s long-run productive potential:

Investment in capital: Greater spending on machinery, infrastructure, and technology raises productive capacity.

Human capital: Improvements in education, training, and skills enhance labour productivity.

Technological progress: Innovations raise efficiency and expand production possibilities.

Labour force size and participation: A larger and more active workforce boosts overall capacity.

Institutional and policy frameworks: Effective legal systems, property rights, and stable governance encourage long-term investment and innovation.

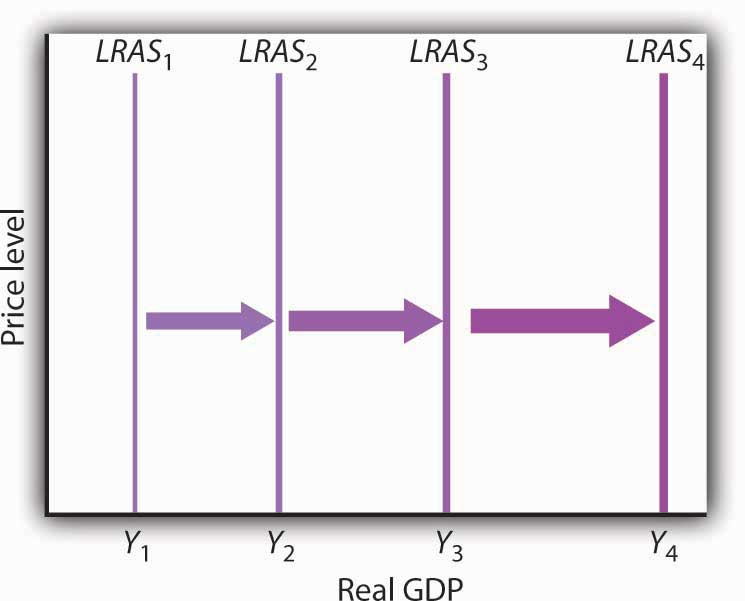

Each factor shifts the long-run aggregate supply (LRAS) curve outward, illustrating an economy’s growing ability to produce goods and services.

Distinguishing Short-Run and Long-Run Growth

It is essential to distinguish between:

Short-run growth: Results from increased utilisation of existing capacity, often through higher aggregate demand (AD).

Long-run growth: Results from expansion of capacity itself, through investment, productivity gains, and labour improvements.

Short-run growth can push the economy above its trend temporarily, but it is unsustainable without supply-side improvements. Long-run growth sets the sustainable path of national income.

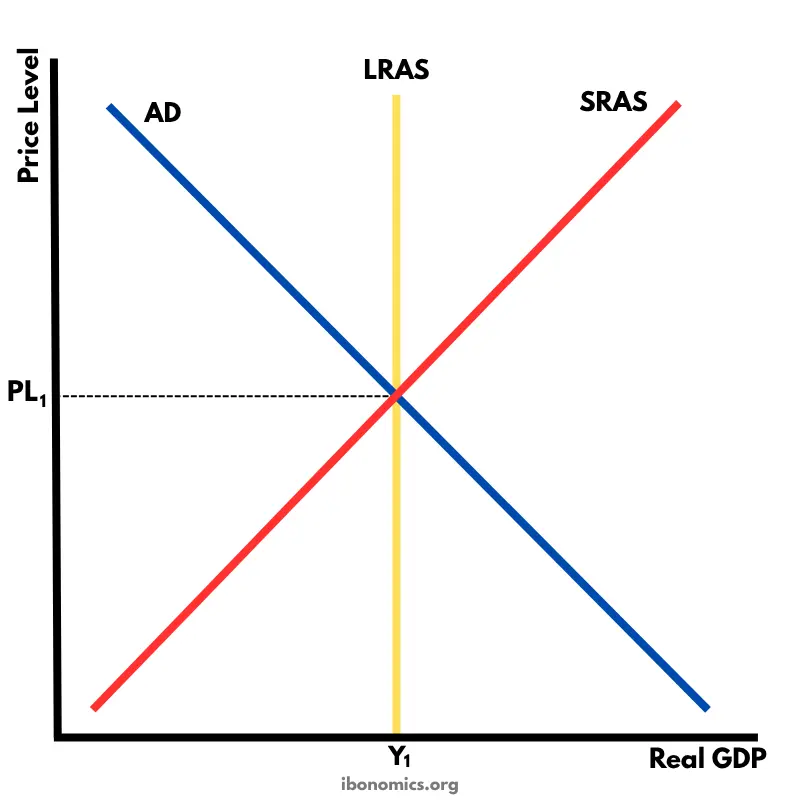

The Classical AD–SRAS–LRAS diagram demonstrates long-run macroeconomic equilibrium, where the LRAS curve is vertical at the full employment level of output, reflecting the economy's potential output. This model underscores that in the long run, output is independent of the price level, aligning with the concept of sustainable economic growth. Source

Graphical Representation

Long-run growth can be illustrated through shifts in the LRAS curve or outward movements of the production possibility curve (PPC):

PPC outward shift: Shows increases in the economy’s maximum possible output due to improved factors of production.

LRAS rightward shift: Demonstrates expansion in productive potential, allowing higher equilibrium output without higher inflation.

Both diagrams emphasise how economies move beyond temporary demand-driven changes to permanent capacity expansion.

The figure shows successive rightward shifts in the LRAS curve, each representing an increase in the economy's potential output due to factors like technological advancements and increased capital. This illustrates the process of economic growth over time. Source

Productivity and Long-Run Growth

A central driver of long-run growth is productivity improvement. Productivity refers to output per unit of input, particularly per worker.

Productivity: The efficiency of production, measured as output per unit of input, often per worker or per hour worked.

Increases in productivity mean the same resources can generate more output, raising the sustainable growth path. For example, technological advances that allow faster production or better resource allocation shift the trend rate upward.

Constraints on Long-Run Growth

Long-run growth is not unlimited. Several constraints may slow or cap growth:

Diminishing returns to capital if investment is not matched by innovation.

Demographic pressures such as ageing populations reducing labour force participation.

Environmental limits on resource use and pollution absorption.

Institutional weaknesses like corruption, poor governance, or weak property rights reducing investment incentives.

Recognising these constraints helps explain why different economies experience different long-run growth rates.

Importance of Long-Run Growth

Sustained long-run growth is vital because it:

Raises living standards by enabling higher real incomes and consumption.

Provides fiscal space through higher tax revenues without raising tax rates.

Supports public investment in healthcare, education, and infrastructure.

Enhances global competitiveness by improving productivity and innovation capacity.

However, policymakers must ensure that growth remains sustainable, balancing expansion with environmental and social considerations.

Measuring Long-Run Growth

Long-run growth is measured by trends in real GDP adjusted for inflation. Economists estimate the potential output of an economy and identify the trend rate by smoothing out cyclical fluctuations.

This allows them to distinguish between temporary accelerations (booms) and genuine improvements in productive capacity. For instance, if GDP rises sharply due to fiscal stimulus but capacity remains unchanged, this does not increase long-run growth.

The graph illustrates the long-run trend rate of economic growth as a steady upward slope, with actual growth rates fluctuating around this trend. These fluctuations represent business cycles, with periods of actual growth above the trend indicating positive output gaps and periods below indicating negative output gaps. Source

Long-Run Growth and Policy

Governments and central banks often design policies to influence the long-run growth rate. These include:

Supply-side policies such as deregulation, tax incentives for research and development, and investment in human capital.

Infrastructure development to reduce bottlenecks and improve efficiency.

Institutional reforms to strengthen legal systems and reduce barriers to business.

By targeting long-run growth, policymakers aim to improve the economy’s resilience and reduce reliance on unsustainable demand-driven growth.

FAQ

The long-run trend rate represents the sustainable average growth path of the economy’s output, based on its productive capacity.

Actual GDP growth fluctuates around this trend due to the economic cycle. Periods of boom may push growth above the trend, while recessions may push it below. The trend itself, however, reflects long-term supply-side potential, not short-term demand-driven changes.

Productivity measures output per unit of input, often per worker or per hour worked.

Higher productivity allows more output from the same resources, raising the sustainable capacity of the economy. Improvements often arise from technological innovation, better education, or improved management practices. Sustained productivity growth is therefore the key driver of long-run growth and shifts the trend rate upwards.

Demographic trends affect both the size and structure of the labour force.

A growing, youthful population can expand the workforce and raise growth potential.

An ageing population may reduce participation and increase dependency ratios, lowering the trend rate.

Migration flows also alter the skills and size of the labour market, with potential effects on long-run growth.

Yes, supply-side policies can have lasting effects if they improve productive capacity.

Examples include:

Investment in education and training, boosting human capital.

Incentives for research and development, encouraging innovation.

Infrastructure spending to reduce bottlenecks in transport and communication.

Such policies shift the long-run aggregate supply curve outward, raising the sustainable growth rate.

If policymakers assume the trend rate is higher than it actually is, they may pursue expansionary policies beyond the economy’s capacity.

This can lead to:

Inflationary pressures, as demand outstrips supply.

Larger output gaps if the economy overheats and then contracts.

Misallocation of resources, where unsustainable growth leads to instability.

Accurate estimation of the trend rate is essential for balanced policy decisions.

Practice Questions

Define the trend rate of economic growth. (2 marks)

1 mark for recognising it is the long-term average rate of growth of real national output.

1 mark for stating it reflects the economy’s productive capacity/supply-side potential.

Explain two supply-side factors that can influence the long-run trend rate of growth in an economy. (6 marks)

Up to 3 marks for each factor explained (maximum 6 marks in total).

1 mark for correctly identifying a factor (e.g., investment in capital, improvements in human capital, technological progress, labour force changes).

1–2 marks for clear development of how this factor raises the economy’s productive capacity and therefore increases the trend rate of growth.

Development must show a clear causal chain (e.g., investment in technology → higher productivity → outward shift in LRAS → higher sustainable growth).