AQA Specification focus:

‘The main UK measures of unemployment, ie the claimant count and the Labour Force Survey measure.’

Unemployment measurement is central to understanding labour market performance and policy. This section explains how the UK measures unemployment, focusing on the claimant count and the Labour Force Survey (LFS), highlighting their differences, strengths, and limitations.

Measuring Unemployment in the UK

Unemployment is a key indicator of economic performance and directly affects welfare, taxation, and government policy. In the UK, two main measures are used: the claimant count and the Labour Force Survey (LFS). Both aim to capture the scale of unemployment but use different definitions, criteria, and data collection methods.

The Claimant Count

The claimant count measures unemployment based on the number of people claiming unemployment-related benefits, primarily Jobseeker’s Allowance (JSA) and, more recently, certain elements of Universal Credit.

Claimant Count: A measure of unemployment based on the number of people receiving unemployment-related benefits, such as Jobseeker’s Allowance or relevant Universal Credit.

This measure has the advantage of being readily available, updated monthly, and relatively inexpensive to compile since it uses administrative records rather than survey data.

However, the claimant count has significant limitations:

It excludes unemployed individuals who do not or cannot claim benefits.

Eligibility rules vary over time, making long-term comparisons difficult.

Not all claimants are necessarily unemployed — some may be working part-time while still receiving partial benefits.

Therefore, the claimant count tends to underestimate actual unemployment levels.

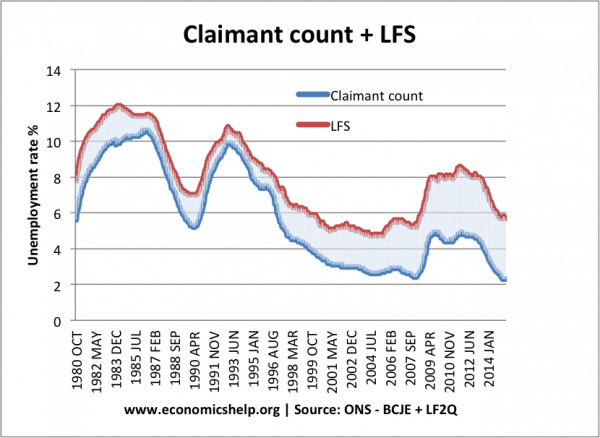

This graph compares the Claimant Count and Labour Force Survey data, demonstrating how the former often underestimates unemployment figures due to its narrower scope. Source

The Labour Force Survey (LFS)

The Labour Force Survey (LFS) is the UK’s official measure of unemployment, conforming to international standards set by the International Labour Organization (ILO). It is based on a large sample survey of households, conducted quarterly by the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

Labour Force Survey (LFS): A sample survey of households measuring unemployment using the ILO definition — people without a job, available to start work, and actively seeking employment.

The LFS defines someone as unemployed if they:

Have been without a job during the reference period.

Are available to start work within two weeks.

Have actively sought work in the past four weeks.

This broader definition captures people who are not claiming benefits but are actively job-hunting, giving a more accurate and internationally comparable measure.

Comparing the Claimant Count and LFS

While both measures aim to track unemployment, they differ in scope, methodology, and interpretation:

Claimant Count

Narrower, administrative measure.

Only includes people receiving benefits.

Quick and inexpensive to produce.

Underestimates total unemployment.

Labour Force Survey

Wider, survey-based measure.

Uses internationally recognised definitions.

Captures those not claiming benefits but still unemployed.

More accurate but costly and less frequent.

Together, the two measures provide complementary insights. Policymakers and economists often use both to understand short-term changes and long-term trends.

Advantages of Using Two Measures

The coexistence of both measures ensures:

Cross-verification of unemployment trends.

Policy targeting — claimant count helps design welfare reforms, while the LFS guides broader labour market policy.

International comparability — LFS aligns with ILO standards, aiding cross-country comparisons.

Limitations of Measurement

Despite their usefulness, both measures face challenges:

Claimant Count Limitations:

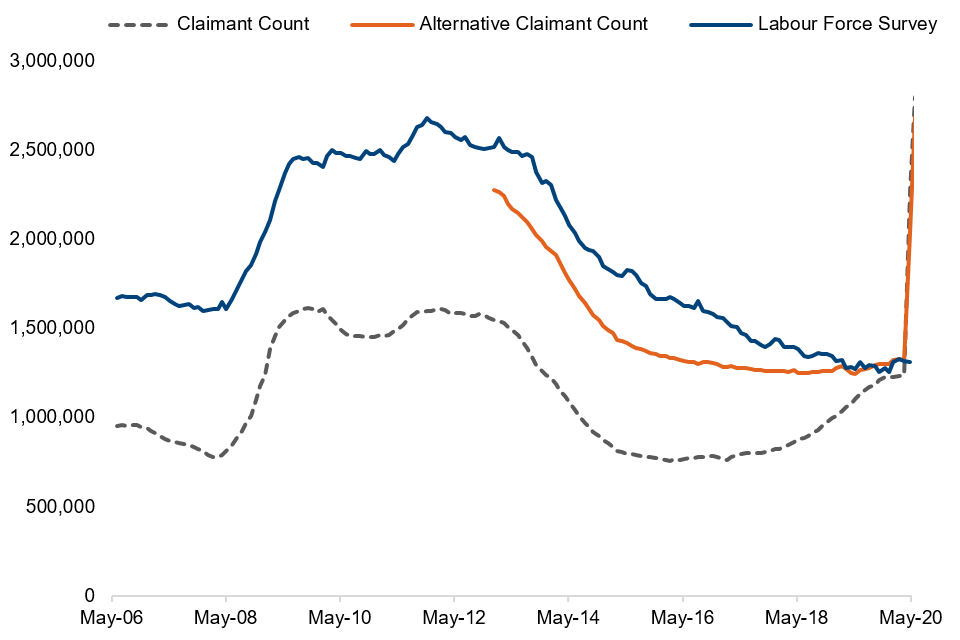

Changes in welfare policy (e.g., Universal Credit reforms) distort long-term trends.

Excludes groups unwilling or unable to claim benefits, such as students or discouraged workers.

Labour Force Survey Limitations:

Survey-based, so results depend on sample accuracy.

More expensive and less timely than claimant data.

Subject to statistical error and seasonal adjustment issues.

Policy Implications

Accurate unemployment measurement is crucial for:

Macroeconomic policy — guides fiscal and monetary responses.

Welfare policy — informs benefit levels and eligibility criteria.

Labour market reforms — influences training, education, and job-creation policies.

If policymakers relied solely on the claimant count, they would underestimate unemployment, risking inadequate support. If they only used the LFS, they might overlook benefit system dynamics that affect behaviour and labour market participation.

This chart compares the Alternative Claimant Count with the Labour Force Survey, illustrating the impact of different data collection methods on unemployment statistics. Source

Key Takeaways

The claimant count is quick, cheap, and benefit-linked but narrow and often underestimates unemployment.

The LFS is broader, internationally comparable, and policy-relevant but slower, more costly, and statistically complex.

Both measures are essential for a well-rounded understanding of UK unemployment trends and for designing balanced economic policy.

FAQ

The claimant count provides quick, inexpensive monthly data that helps track short-term changes in benefit claims. However, it misses those not claiming benefits.

The Labour Force Survey captures a wider group, following international standards, making it more accurate for long-term comparisons and global benchmarking. Together, they balance speed with accuracy.

The LFS follows the ILO standard to ensure consistency across countries.

According to this definition, unemployed individuals must:

Be without a job during the reference period.

Be available to start work within two weeks.

Have actively searched for work in the past four weeks.

This creates comparability across economies and avoids distortions caused by national benefit systems.

The claimant count misses groups who are not eligible or do not apply for benefits. These can include:

Young people not entitled to benefits.

Students actively seeking part-time work.

Married partners supported by household income.

Discouraged workers who have stopped claiming but still want work.

The LFS captures these groups, giving a fuller picture of unemployment.

Universal Credit has replaced several benefits, including Jobseeker’s Allowance, meaning the claimant count now covers a broader group.

This reform has blurred the boundary between the unemployed and those in low-paid or part-time work. As a result, some employed individuals still appear in the claimant count, reducing its precision as a measure of pure unemployment.

Policy changes often alter eligibility rules for unemployment benefits.

For example:

Stricter conditions for claiming reduce the claimant count without a real fall in unemployment.

Reforms like Universal Credit expand eligibility, inflating the figures.

These changes mean long-term trends in claimant data may reflect benefit policy adjustments rather than genuine labour market shifts.

Practice Questions

Define the claimant count measure of unemployment. (2 marks)

1 mark for identifying that the claimant count measures the number of people claiming unemployment-related benefits.

1 mark for correctly naming examples such as Jobseeker’s Allowance or relevant Universal Credit.

Explain two differences between the claimant count and the Labour Force Survey as measures of unemployment. (6 marks)

Up to 3 marks for each valid difference explained (2 marks for identification, 1 mark for development).

Valid differences include:

Claimant count is based on benefit claims, whereas the LFS uses a household survey.

Claimant count is narrower (only benefit claimants), while the LFS includes those actively seeking work but not claiming.

Claimant count is quicker and cheaper to produce, while the LFS is more costly and less frequent.

LFS is internationally comparable under ILO standards; claimant count is not.

Maximum of 6 marks in total.