AQA Specification focus:

‘The concept of, and the factors which determine, the natural rate of unemployment.’

Introduction

The natural rate of unemployment represents a key concept in macroeconomics, helping economists explain persistent unemployment, even when the economy is at full capacity.

Understanding the Natural Rate of Unemployment

The natural rate of unemployment refers to the level of unemployment that persists in an economy when the labour market is in equilibrium, meaning aggregate demand equals aggregate supply. It does not imply zero unemployment but rather the level consistent with stable inflation and efficient allocation of resources.

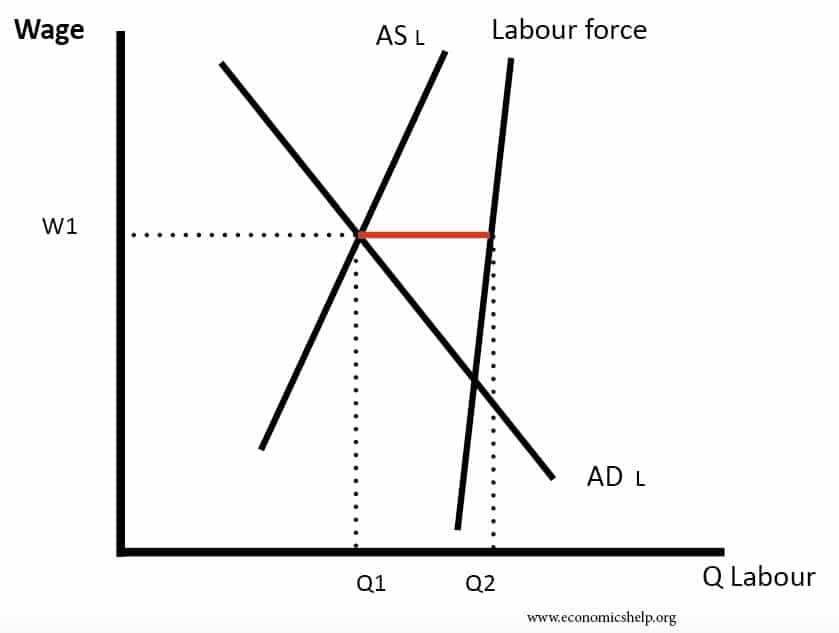

This diagram depicts the equilibrium in the labour market, where the labour supply and demand curves intersect at the natural rate of unemployment. It highlights that the natural rate includes frictional and structural unemployment but excludes cyclical unemployment. Source

Natural Rate of Unemployment: The unemployment rate that exists when the labour market is in equilibrium, including frictional and structural unemployment, but excluding cyclical unemployment.

This concept helps policymakers distinguish between temporary fluctuations in unemployment caused by recessions and the underlying long-term rate inherent to the economy.

Components of the Natural Rate of Unemployment

The natural rate is composed of different forms of unemployment that exist even in healthy economies:

Frictional unemployment – short-term unemployment as workers transition between jobs.

Structural unemployment – unemployment caused by mismatches between workers’ skills and available jobs.

Seasonal unemployment – though minor, certain industries create regular unemployment due to seasonal patterns.

Cyclical unemployment, which arises from downturns in the economic cycle, is not included in the natural rate since it reflects demand deficiency rather than equilibrium.

Factors Determining the Natural Rate of Unemployment

A variety of demand-side and supply-side factors influence the natural rate. These include:

Labour Market Flexibility

Wage flexibility: If wages are sticky downwards, firms may retain unemployment above the natural rate.

Labour mobility: Regional and occupational mobility affect how quickly workers can move to where jobs are available.

Skills and Training

Education and training: Economies with better retraining schemes and adaptable education systems reduce structural unemployment.

Technological change: Rapid innovation can increase structural unemployment if workers’ skills fail to keep pace.

Government Policies

Taxation and welfare systems: High unemployment benefits may discourage active job seeking, raising the natural rate.

Labour regulations: Strict employment protection can discourage firms from hiring, raising the long-run equilibrium unemployment.

Demographics

Youth unemployment: Younger workers often experience higher frictional unemployment due to frequent job changes.

Ageing workforce: Older workers may face difficulties in retraining, increasing long-term structural unemployment.

Market Institutions

Trade unions: Strong unions can push wages above equilibrium levels, raising unemployment.

Minimum wage laws: If set above market-clearing levels, they can generate real wage unemployment.

The Natural Rate and Inflation

The natural rate is closely tied to inflation expectations and the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (NAIRU).

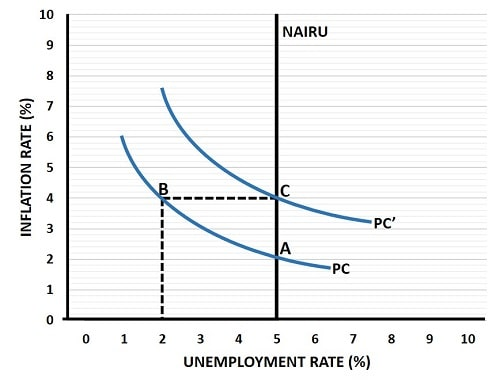

This diagram illustrates the relationship between the NAIRU and the long-run Phillips curve, showing that the natural rate of unemployment corresponds to a stable rate of inflation. It demonstrates that reducing unemployment below the natural rate can lead to rising inflation. Source

NAIRU: The level of unemployment consistent with stable inflation, below which inflation tends to accelerate.

This concept suggests that attempts to reduce unemployment below the natural rate through expansionary demand-side policies will cause accelerating inflation without sustainable job gains.

Interaction with Economic Policy

Understanding the natural rate is crucial for policymakers:

Monetary policy: Central banks use interest rates to stabilise inflation around the natural rate of unemployment.

Fiscal policy: Governments may invest in training and education to reduce the natural rate over time.

Supply-side policies: Measures such as deregulation, welfare reform, and improving labour mobility aim to shift the natural rate downward.

Efforts to reduce unemployment must distinguish between cyclical fluctuations and the structural or frictional unemployment that makes up the natural rate.

Long-Run Implications

The natural rate is not fixed; it evolves with changes in labour markets, technology, and institutions. Economies that adapt effectively with supply-side reforms and skills development can lower their natural rate. Conversely, rigid labour markets, inadequate training, or technological displacement can increase it.

A low natural rate signals efficiency and adaptability.

A high natural rate indicates structural problems and persistent mismatches.

In macroeconomic analysis, this concept forms a bridge between unemployment, inflation, and long-term growth trends.

FAQ

Full employment does not mean zero unemployment but rather the lowest sustainable level of unemployment without causing inflation.

The natural rate of unemployment reflects this concept in practice, representing the equilibrium level where frictional and structural unemployment still exist, but cyclical unemployment does not.

The natural rate shifts with structural changes in the economy, including:

Advances in technology requiring new skills

Shifts in demographics, such as more young people entering the labour market

Policy reforms that change labour flexibility or incentives to work

As these factors evolve, the equilibrium level of unemployment adjusts accordingly.

Globalisation can increase competition and shift production abroad, raising structural unemployment if workers’ skills do not match new job demands.

At the same time, it can create new opportunities in trade-related industries, potentially lowering the natural rate if workers adapt quickly.

It is not directly observable and must be estimated using models that link unemployment to inflation trends.

Economists often look at the point where inflation stabilises, known as the NAIRU, and use long-term labour market data to approximate the natural rate.

Policies that target structural and frictional unemployment are most effective:

Investment in education and retraining programmes

Encouraging geographical and occupational mobility

Reforming benefits to strengthen work incentives

Unlike demand-side policies, these measures shift the underlying equilibrium of the labour market.

Practice Questions

Define the natural rate of unemployment. (2 marks)

1 mark for recognising that it is the unemployment rate when the labour market is in equilibrium / full employment.

1 mark for noting that it includes frictional and structural unemployment but excludes cyclical unemployment.

Explain two factors that could cause the natural rate of unemployment to change over time. (6 marks)

Up to 2 marks for identifying each factor (maximum 2 factors).

Example: changes in labour market flexibility, such as wage rigidity.

Example: changes in skills and training affecting structural unemployment.

Up to 2 marks for explanation of how each factor influences the natural rate.

Example: better training reduces mismatches between jobs and skills, lowering the natural rate.

Example: stricter labour laws can discourage firms from hiring, raising the natural rate.

Award full 6 marks for two well-developed factors with clear explanations.

Maximum 4 marks if only one factor is explained in detail.