AQA Specification focus:

‘They should understand that a negative output gap is linked to cyclical unemployment and that supply-side causes of unemployment affect the position of the long-run aggregate supply curve.’

Understanding the relationship between output gaps, cyclical unemployment, and long-run aggregate supply (LRAS) is vital for analysing fluctuations in economic activity and the long-run performance of an economy.

Output Gaps

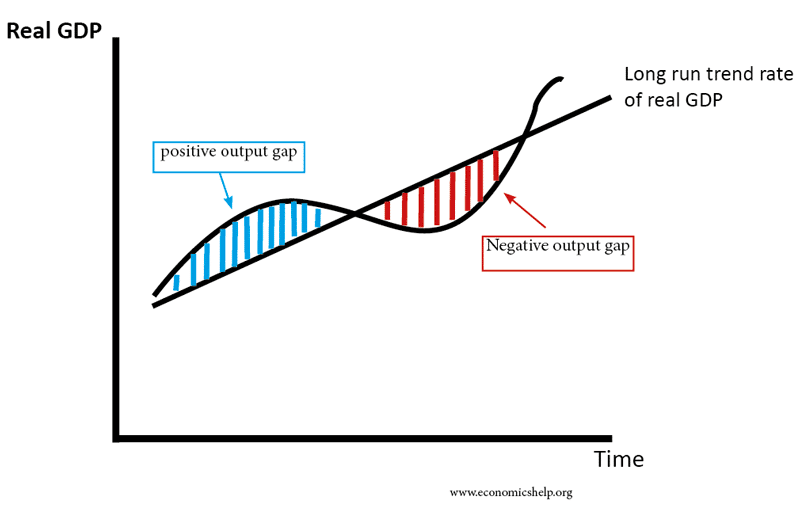

An output gap occurs when there is a difference between actual real GDP and potential GDP (the economy’s maximum sustainable output).

Output Gap: The difference between actual output (real GDP) and potential output (trend output). A positive output gap means output is above trend; a negative output gap means output is below trend.

Output gaps highlight whether the economy is operating above or below capacity. They are central to evaluating macroeconomic performance.

Positive output gap: Actual output exceeds potential, often leading to inflationary pressures due to excess demand.

Negative output gap: Actual output falls below potential, often linked to higher unemployment and underutilisation of resources.

Cyclical Unemployment and Negative Output Gaps

Cyclical unemployment is directly linked to downturns in the economic cycle. When aggregate demand is insufficient, firms cut production, creating a negative output gap and job losses.

Cyclical Unemployment: Unemployment that arises when demand for goods and services falls, reducing production and causing workers to be laid off. It is associated with recessions.

Key connections between negative output gaps and cyclical unemployment:

Falling demand → lower production → redundancies.

Idle capital and labour remain underutilised.

Government revenues fall as unemployment rises, worsening fiscal positions.

Positive Output Gaps and Inflation Pressures

While negative gaps create cyclical unemployment, positive output gaps are linked to inflationary risks. When output is above the economy’s sustainable level, resources are overused.

Implications of positive gaps:

Wages and input prices rise as firms compete for scarce resources.

Demand-pull inflation accelerates.

Central banks may intervene with contractionary policies to stabilise inflation.

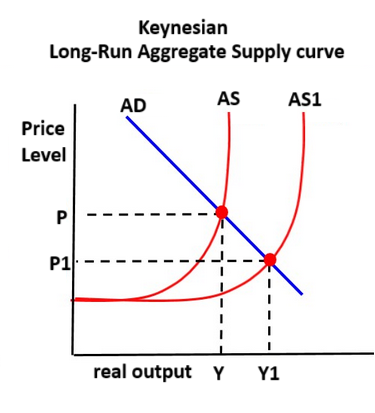

The Keynesian LRAS curve demonstrates how an economy can function below full employment without immediate inflationary pressure. The horizontal section indicates unused capacity, leading to negative output gaps and cyclical unemployment. Source

Long-Run Aggregate Supply (LRAS) and Unemployment

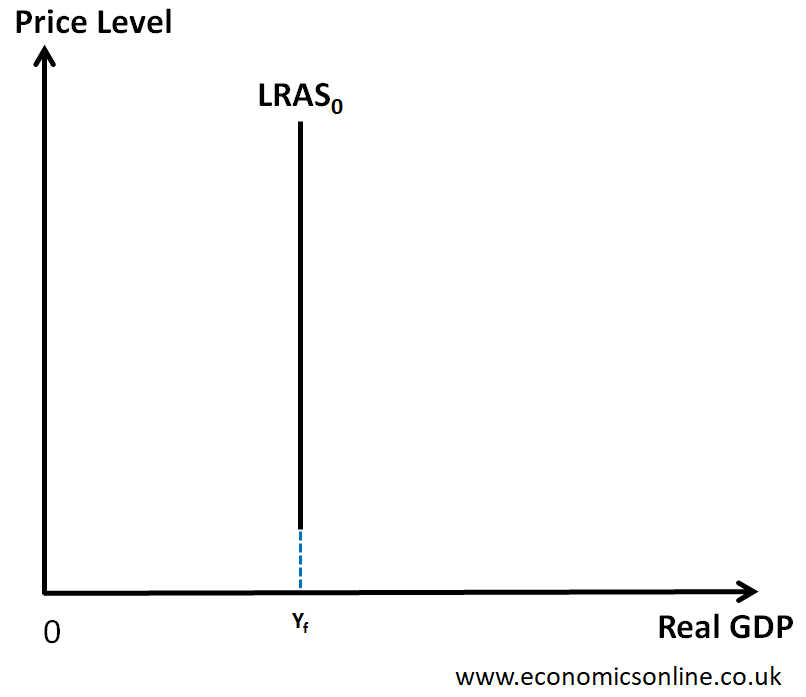

The long-run aggregate supply curve (LRAS) represents the economy’s productive potential. It is vertical because, in the long run, output is determined by supply-side factors, not demand.

Long-Run Aggregate Supply (LRAS): The total output an economy can produce when resources are fully employed, determined by supply-side factors such as labour, capital, technology, and efficiency.

The position of LRAS reflects structural aspects of the economy:

Rightward shift: Improvements in productivity, investment in technology, or education and training.

Leftward shift: Declines in labour force participation, reduced capital stock, or persistent structural unemployment.

The classical LRAS curve is vertical at YFE, indicating that in the long run, the economy produces at its potential output, and changes in aggregate demand only affect the price level, not output. Source

Linking Supply-Side Factors to Unemployment

While cyclical unemployment is linked to demand deficiencies, supply-side causes of unemployment also matter because they directly affect LRAS:

Structural unemployment: Occurs when workers’ skills do not match job vacancies. This reduces the effective labour force, lowering potential output and shifting LRAS leftward.

Frictional unemployment: Short-term job search unemployment, usually less harmful, but if prolonged, it can hinder efficiency.

Real wage unemployment: When wages are kept artificially above equilibrium levels, labour markets cannot clear, restricting LRAS.

These supply-side factors reduce the productive capacity of the economy and can prevent actual output from converging with potential output.

Output Gaps, Policy, and Economic Stability

Policymakers closely monitor output gaps to design interventions:

Negative gaps: May justify expansionary fiscal or monetary policies to boost aggregate demand and reduce cyclical unemployment.

Positive gaps: Require contractionary measures to cool inflationary pressures.

However, policies must also account for long-run supply-side improvements to ensure growth is sustainable. For example:

Investment in education and training → increases human capital.

Infrastructure development → boosts productivity.

Labour market reforms → reduce structural rigidities.

The AD/AS model illustrates how shifts in aggregate demand can lead to output gaps. A negative gap (Y1 < YFE) indicates underutilised resources and potential cyclical unemployment, while a positive gap (Y1 > YFE) suggests inflationary pressures. Source

Indicators of Output Gaps and Unemployment

Economists rely on macroeconomic indicators to assess the scale and implications of output gaps:

Real GDP growth rates: Show whether output is above or below potential.

Unemployment statistics: High cyclical unemployment indicates negative gaps.

Inflation trends: Rising inflation signals a positive gap; deflationary pressure signals a negative gap.

Interconnections Between Output Gaps, Cyclical Unemployment and LRAS

The relationship can be summarised as follows:

Negative output gap → cyclical unemployment rises → economy underutilises resources.

Positive output gap → inflationary pressure builds → potential overheating.

Shifts in LRAS → alter the economy’s long-run trend rate of growth and affect the persistence of unemployment.

Together, these concepts help explain why short-term demand fluctuations and long-term supply capacity both matter for understanding economic stability and performance.

FAQ

Potential output represents the maximum sustainable level of output when resources are fully employed. It acts as the benchmark against which actual output is compared.

If actual output falls short of potential, a negative output gap occurs. If it exceeds potential, a positive output gap arises. This comparison underpins how economists assess whether the economy is underperforming or overheating.

Estimating output gaps is difficult because potential output cannot be directly observed. Policymakers rely on models and indicators such as:

Trends in real GDP over time

Labour market data (e.g., unemployment rates)

Capacity utilisation in industry

These estimates are subject to revision as more data becomes available.

Cyclical unemployment directly reflects demand deficiency and negative output gaps. It rises when output falls below potential due to reduced aggregate demand.

By contrast, structural unemployment arises from long-term mismatches in skills or regional imbalances. While cyclical unemployment narrows as demand recovers, structural unemployment persists even if the output gap closes.

In theory, positive output gaps usually cause inflation, but exceptions exist. If productivity rises sharply, the economy may temporarily produce above trend without price pressures.

Additionally, global factors such as falling commodity prices or strong exchange rates can offset inflation, even when resources are overused domestically.

Supply-side shocks, such as sudden changes in energy costs or labour force participation, can alter the economy’s productive potential.

If LRAS shifts left, the output gap widens at the same level of demand.

Unemployment may remain high, not from cyclical causes, but because potential output has fallen.

This makes it harder to distinguish between cyclical and structural issues in the labour market.

Practice Questions

Explain the difference between a positive output gap and a negative output gap. (2 marks)

1 mark for stating that a positive output gap occurs when actual output is above potential output.

1 mark for stating that a negative output gap occurs when actual output is below potential output.

(2 marks maximum)

Discuss how a negative output gap may be linked to cyclical unemployment and the implications for the long-run aggregate supply curve (LRAS). (6 marks)

1 mark for defining cyclical unemployment (linked to downturns in the economic cycle/insufficient demand).

1 mark for defining a negative output gap (actual output below potential output).

1 mark for explaining that a fall in aggregate demand leads to reduced output, creating unemployment.

1 mark for linking cyclical unemployment to underutilisation of resources in the economy.

1 mark for explaining that supply-side causes of unemployment (e.g., structural) can shift LRAS leftward.

1 mark for evaluative comment (e.g., cyclical unemployment may be temporary if demand recovers; supply-side issues make unemployment more persistent and affect LRAS).

(6 marks maximum)