AQA Specification focus:

‘They should also be able to assess the view that introducing the price mechanism and markets into some fields of human activity may be undesirable and is likely to affect the nature of the activity, eg introducing a market for blood changes the nature of the transaction and the incentives involved.’

In some contexts, applying the price mechanism raises deep ethical, social, and economic concerns. Sensitive areas test the boundaries of whether markets should allocate resources.

Understanding Sensitive Areas

The price mechanism refers to the way prices act as signals, ration scarce resources, and provide incentives for buyers and sellers. While efficient in many markets, its extension to certain sensitive areas is controversial.

Sensitive areas often involve goods and services tied to moral values, public welfare, or human dignity. Examples include:

Healthcare and the allocation of life-saving treatments.

Education and equal access to opportunities.

Environmental resources, such as clean air and biodiversity.

Human body parts, such as blood and organs.

Why Sensitive Areas Matter

Introducing markets into such areas may:

Alter the nature of the activity, turning what was once viewed as a civic duty or right into a commercial transaction.

Create ethical dilemmas, especially where human dignity or equity is at stake.

Lead to perverse incentives, where profit outweighs social responsibility.

Arguments in Favour of Market Use

Efficiency and Allocation

Markets can allocate scarce resources quickly, reducing waiting times and encouraging supply. For instance, financial incentives could increase the availability of donated organs.

Incentives for Innovation

Where markets are permitted, firms may innovate to improve service quality, technology, or access. For example, private healthcare markets often push investment into cutting-edge treatments.

Choice and Autonomy

Markets allow individuals to exercise freedom of choice, reflecting their preferences and willingness to pay.

Autonomy: The ability of individuals to make decisions independently, particularly about their own lives and resources.

When applied in markets, autonomy supports personal responsibility and consumer sovereignty.

Arguments Against Market Use

Commodification of Human Life

Turning certain goods and services into commodities risks undermining their intrinsic value. For example, creating a market for blood may reduce voluntary donation and treat blood as a commercial good rather than a shared resource.

Inequality and Access

Markets allocate resources based on purchasing power rather than need. This can create or widen inequalities:

Wealthier individuals gain access to critical services.

Poorer groups face exclusion or limited access.

Distortion of Incentives

In sensitive contexts, markets may distort behaviour. For instance:

Financial incentives for organ donation could lead to exploitation of vulnerable populations.

Education markets could prioritise profit-driven subjects over socially valuable ones.

Crowding Out Altruism

Markets can undermine non-market motivations. If people are paid for blood donation, altruistic donation may decline, reducing overall supply.

Crowding Out: The phenomenon where introducing financial incentives reduces intrinsic or non-financial motivations, leading to lower overall participation or contribution.

This highlights the tension between market incentives and social values.

Case Examples

Market for Blood

Historically, voluntary donation has ensured a safe and reliable blood supply.

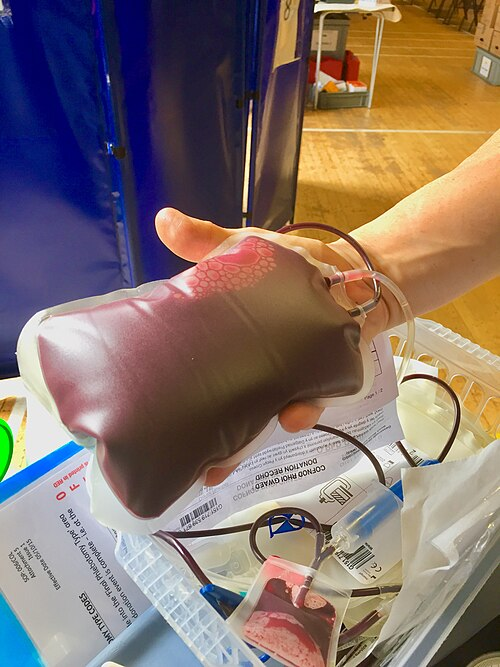

A unit of donated whole blood in a clinical setting, labelled and ready for testing and transfusion. This highlights why many systems prioritise voluntary, unpaid donation to maintain safety, trust and altruistic supply. Source

Healthcare Services

In purely market-driven systems, access depends on ability to pay.

This raises ethical concerns about fairness in life-or-death situations.

Environmental Resources

Markets for pollution permits can price environmental damage.

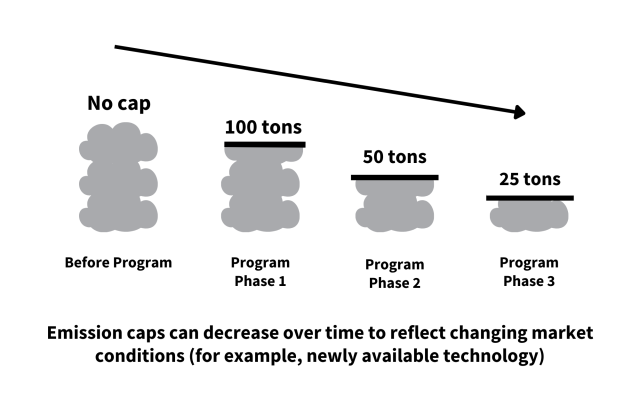

EPA schematic illustrating emissions caps that decline over time in a cap-and-trade programme, reducing total pollution while allowing trading of allowances. It visualises the market signal with environmental safeguards—connecting efficiency with designed ethical constraints. Source

Yet critics argue that treating nature as tradable ignores its non-economic value.

Ethical and Economic Evaluation

Ethical Lens

Some goods are considered rights rather than commodities, such as healthcare and education.

Markets in these areas risk eroding values of fairness and solidarity.

Economic Lens

Markets are praised for allocative efficiency, but this assumes perfect information and equal access, which are rarely present in sensitive areas.

Negative externalities may arise, harming society in the long run.

Negative Externality: A cost imposed on third parties not reflected in the market price, such as pollution from industry or unequal access to education.

This demonstrates how market allocation in sensitive areas may worsen, rather than improve, social outcomes.

Balancing Markets and Alternatives

Rather than full marketisation, societies often combine:

Public provision: e.g., state-funded healthcare systems.

Regulation: to ensure fair access and prevent exploitation.

Hybrid models: blending markets with ethical oversight, such as regulated carbon markets.

Key approaches include:

Establishing limits on what can be commodified.

Using non-market allocation (e.g., lotteries for scarce treatments).

Encouraging voluntary contribution alongside regulated markets.

Final Considerations

The question of whether markets should operate in sensitive areas forces students to assess trade-offs between efficiency and equity, autonomy and dignity, innovation and ethics. The AQA specification stresses that introducing markets into these contexts may change the fundamental nature of the activity and the incentives involved, making evaluation central to exam preparation.

FAQ

In sensitive areas like healthcare, introducing prices and markets can create moral hazard, where individuals or providers take greater risks because they are shielded from the consequences.

For instance, private hospitals might over-prescribe expensive treatments if patients or insurers are covering the cost. Similarly, people with access to paid organ markets could engage in riskier behaviour, knowing a supply of replacements is available.

Acceptance varies widely across societies.

In some cultures, buying and selling blood or organs is seen as morally unacceptable, violating values of dignity and altruism.

In others, market exchanges are more accepted if they help meet urgent medical needs.

Public trust, religious beliefs, and historic norms strongly influence whether marketisation is tolerated.

Governments often set clear boundaries to protect public interest.

Laws may prohibit payment for organs or blood to preserve safety and ethical standards.

Regulations restrict pricing in healthcare to ensure fairness.

Oversight bodies monitor incentives, ensuring markets do not exploit vulnerable groups.

While often criticised, markets can sometimes improve access.

For example, allowing regulated private provision in healthcare may reduce pressure on state systems, shortening waiting times for all. Subsidised markets, such as carbon credit trading, may redistribute funds from polluters to cleaner producers, indirectly promoting equity.

However, strict safeguards are necessary to avoid reinforcing inequalities.

‘Repugnant markets’ are those that societies reject even if they could increase efficiency.

Examples include markets for children, human organs, or votes. The concept highlights that efficiency alone cannot justify every market; social norms and ethics place limits.

Understanding repugnance helps explain why some markets never emerge despite potential economic benefits.

Practice Questions

Define the term crowding out in the context of using markets in sensitive areas. (2 marks)

1 mark: Identifies that crowding out refers to financial incentives reducing intrinsic or altruistic motivations.

1 mark: Explains that this may lead to a fall in overall participation or contributions (e.g., fewer voluntary blood donations).

Assess two arguments against using the price mechanism in sensitive areas such as healthcare or blood donation. (6 marks)

Up to 2 marks: Identification of valid arguments against (e.g., inequality of access, commodification of human life, crowding out altruism, distorted incentives).

Up to 2 marks: Explanation of each argument with economic reasoning (e.g., markets allocate by purchasing power not need, leading to exclusion of poorer groups).

Up to 2 marks: Application and limited evaluation (e.g., examples such as blood donation or healthcare waiting lists, possible unintended consequences).

Maximum 6 marks.