Edexcel Specification focus:

‘Inequality of access to education, housing, healthcare and income opportunities can influence vulnerability and resilience.’

This topic explores how unequal access to essential resources increases community vulnerability and reduces resilience to tectonic hazards such as earthquakes, volcanoes and tsunamis.

Understanding Vulnerability in the Context of Inequality

What is Vulnerability?

Vulnerability: The degree to which a population is susceptible to, or unable to cope with, the adverse impacts of a hazard.

Communities living in tectonically active regions face different levels of vulnerability based on their ability to prepare for, respond to, and recover from tectonic hazards. This ability is shaped significantly by social and economic inequalities.

Resilience and Its Importance

Resilience: The capacity of individuals, communities or systems to absorb and recover from hazard impacts, while maintaining essential functions.

More resilient communities are better able to withstand tectonic events with reduced loss of life, economic damage and long-term disruption.

Dimensions of Inequality Affecting Tectonic Vulnerability

1. Inequality in Access to Education

Limited access to education significantly increases vulnerability. Education affects:

Awareness of hazards: Populations with higher literacy rates are more likely to understand hazard warnings and evacuation procedures.

Preparedness: Educated individuals are more likely to participate in community drills and interpret risk information correctly.

Response efficiency: Basic first aid and safety knowledge improve survival chances during and after disasters.

Populations with low literacy may misinterpret official instructions, delaying evacuation or increasing exposure to danger.

2. Inequality in Access to Housing

Poor housing conditions increase the likelihood of severe impacts from tectonic hazards:

Informal housing often lacks structural integrity and building regulation compliance, making it highly susceptible to collapse during earthquakes or lava flows.

Settlements may be located in hazard-prone areas due to lack of affordable, safe land.

Overcrowded housing compounds risks of casualties and complicates evacuation.

In contrast, wealthier groups benefit from hazard-resistant construction, insurance, and government-provided risk assessments.

3. Inequality in Access to Healthcare

Healthcare access determines how well a population can cope with injuries and disease outbreaks following a tectonic event:

Inadequate facilities can lead to higher mortality from otherwise treatable injuries.

Delays in care worsen outcomes for vulnerable groups, including children, the elderly, and the disabled.

Underfunded services may collapse under pressure during a major hazard event.

Conversely, access to modern healthcare supports rapid treatment, mental health support, and post-disaster recovery, reducing long-term vulnerability.

4. Inequality in Income Opportunities

Economic inequality plays a central role in shaping vulnerability and resilience:

Low-income individuals often cannot afford insurance, retrofitting, or early warning technology.

Economic insecurity may force people to remain in dangerous zones despite known hazards.

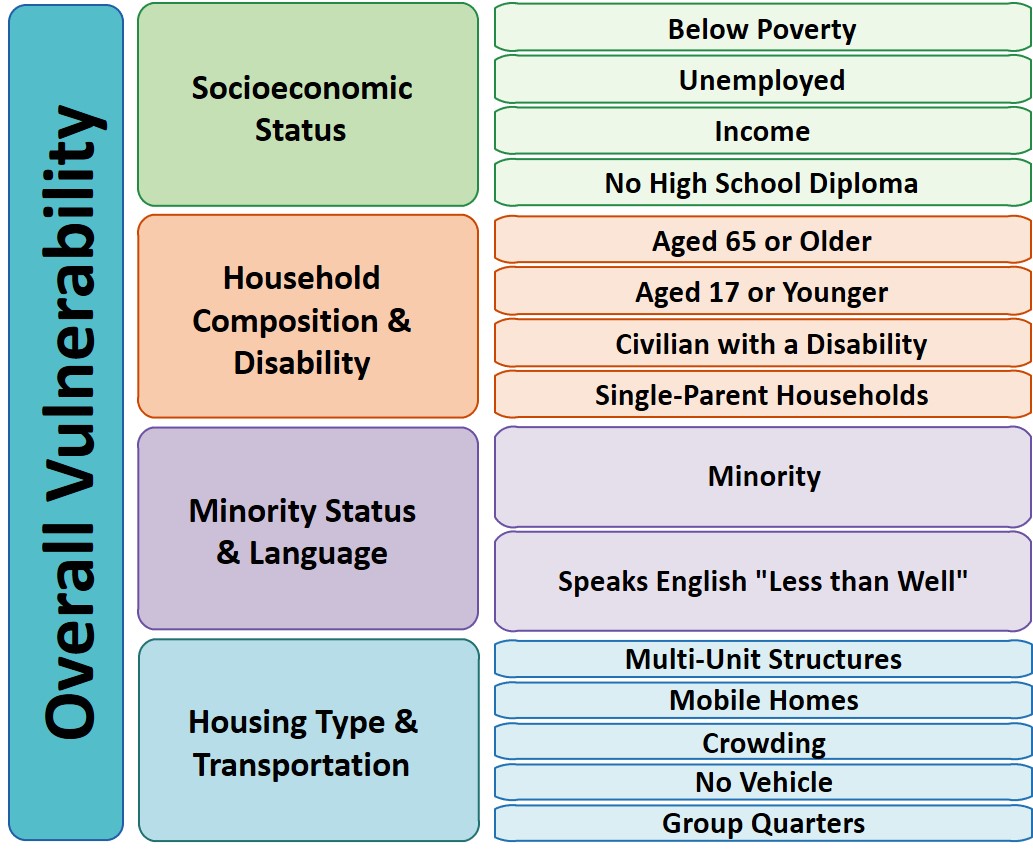

Excerpt from the CDC Social Vulnerability Index showing the Socioeconomic Status theme with indicators like “Below Poverty Line” and “No High School Diploma”. Source

Wealthier individuals and regions are typically able to absorb disaster costs through savings, government aid, and access to credit.

Interplay Between Inequality and Tectonic Risk

Systemic Nature of Inequality

Social and economic inequalities are not isolated — they tend to reinforce one another, amplifying vulnerability.

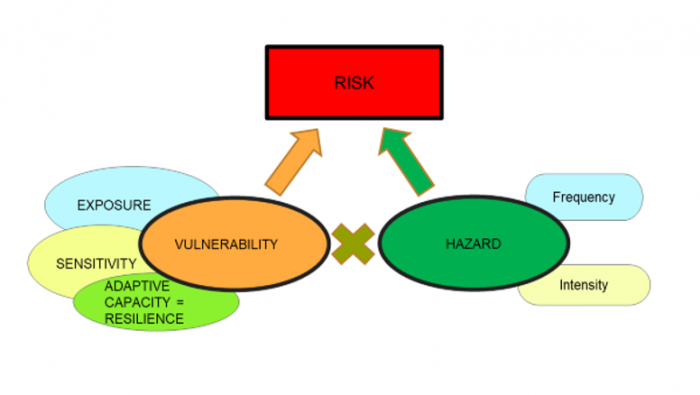

A three‑circle Venn diagram of Hazard, Vulnerability, and Exposure overlapping to define Risk; originally for coastal contexts, it conceptually applies to tectonic hazards. Source

For example:

Low education limits job access, which restricts income.

Low income leads to poor housing, reduced healthcare access, and limited disaster preparedness.

These interconnected factors reduce resilience and lengthen recovery times.

Urbanisation and Marginalisation

In rapidly urbanising areas, especially in emerging and developing countries, large informal settlements grow on unstable land:

These settlements may be unmapped and excluded from official disaster management plans.

Weak governance or corruption can limit investment in risk reduction for marginalised communities.

The most vulnerable—women, children, ethnic minorities—often experience the worst outcomes from tectonic disasters.

Pathways to Reducing Vulnerability

Reducing Inequality to Increase Resilience

Efforts to tackle social inequality are essential for improving a community’s ability to cope with tectonic hazards. Key strategies include:

Education access: Expand hazard-related education in schools and communities.

Social housing programmes: Invest in safe, affordable housing in low-risk areas.

Healthcare infrastructure: Improve access in rural and high-risk zones.

Economic support: Provide microfinance, income diversification, and insurance access.

Reducing these disparities helps close the resilience gap between different social groups.

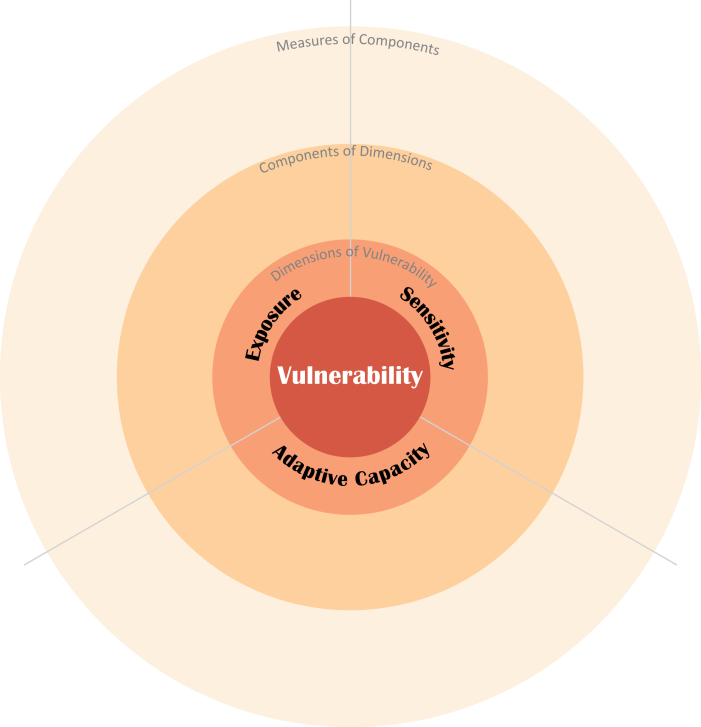

A three‑ring Vulnerability Scoping Diagram showing the dimensions of vulnerability (exposure, sensitivity, adaptive capacity) and measures including educational attainment, household income, and health & nutrition. Source

Role of International and National Agencies

Governments, NGOs, and international bodies all play a role in addressing inequality:

NGOs often target underserved communities with preparedness training, healthcare, and post-disaster aid.

National governments can legislate for inclusive planning and equity-focused development.

International partnerships may offer funding and technology to improve resilience in the most vulnerable regions.

These collective efforts help ensure that tectonic risk does not translate into catastrophic outcomes due to social inequality.

FAQ

Inequality limits access to technology and communication infrastructure, especially in low-income or remote areas. This reduces the reach of early warning systems for earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and tsunamis.

Wealthier areas are more likely to have:

Internet and mobile networks for warning dissemination

Public address systems and sirens

Institutional support for training and maintenance

In contrast, marginalised communities may not receive alerts in time or may not understand them due to language or education barriers, reducing the system’s effectiveness.

Informal settlements often arise in hazardous areas such as steep slopes, fault lines, or volcanic flanks, where land is cheaper or unregulated.

Key vulnerabilities include:

Poorly constructed buildings using low-quality materials

Lack of formal planning, drainage, or infrastructure

Limited access to emergency services and evacuation routes

Residents may also lack legal land tenure, making post-disaster recovery more difficult or disincentivised by authorities.

Yes, cultural and linguistic differences can hinder hazard communication and emergency response.

For example:

Non-native speakers may misunderstand warnings or official instructions.

Cultural beliefs may influence trust in authorities or willingness to evacuate.

Traditional knowledge systems may conflict with scientific risk advice.

Inclusive communication strategies that consider language diversity and cultural norms are vital to reducing vulnerability in multicultural communities.

Wealthier groups often recover faster due to better access to insurance, savings, and government support. In contrast, vulnerable populations face slower or incomplete recovery.

Factors delaying recovery include:

Loss of informal jobs with no compensation

Ineligibility for formal aid due to lack of documentation

Mental health impacts and displacement from communities

Inequality affects not just immediate impacts but also the speed and sustainability of rebuilding lives and livelihoods.

Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) help bridge gaps where state support is limited or absent.

Their roles include:

Delivering education and awareness campaigns

Providing first aid, shelters, and clean water during emergencies

Supporting community preparedness through training and resources

Advocating for policy changes and inclusion of marginalised groups

NGOs are especially important in informal or rural communities often overlooked in official disaster planning.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks):

Explain how lack of access to healthcare can increase vulnerability to tectonic hazards.

Mark Scheme:

Award 1 mark for identifying a relevant factor, and 1 mark for elaboration or linkage to hazard impact.

1 mark: Poor healthcare limits treatment after hazard events.

1 mark: This can increase death rates and slow recovery, especially in rural or under-resourced areas.

Question 2 (6 marks):

Assess the role of economic inequality in increasing vulnerability to tectonic hazards.

Mark Scheme:

Level 1 (1–2 marks):

Basic points stated with little or no development.

Generic statements with limited geographical terminology.

Example: Poor people are more at risk.

Level 2 (3–4 marks):

Clear explanation of economic inequality and its effects on vulnerability.

Some development with linked examples or consequences.

Example: Low-income households may not afford hazard-resistant housing, which increases risk during an earthquake.

Level 3 (5–6 marks):

Well-developed response assessing how economic inequality contributes to vulnerability.

Use of geographical terminology and understanding of hazard impacts.

May include contrast with wealthier groups or multiple dimensions of economic disadvantage.

Example: Economic inequality restricts access to early warning systems, insurance, and relocation options. This leads to higher exposure and slower recovery, particularly in developing countries where informal settlements are common.