IB Syllabus focus:

‘Perspectives arise from norms, science, laws, economics, events, values and lived experience, leading to positions and actions; arguments are reasons used to support or challenge a perspective.’

Human perspectives on the environment are shaped by multiple influences including cultural values, scientific knowledge, legal frameworks, and lived experiences. These perspectives drive arguments, decisions, and actions.

Perspectives and Their Origins

Norms

Norms are socially accepted behaviours and practices. They act as guiding standards for communities, influencing how people perceive environmental problems and acceptable solutions.

Norms: Shared expectations or rules within a society that shape behaviour and perceptions.

Social norms vary widely across cultures. For example, a norm of recycling may be strong in one community but almost absent in another, shaping perspectives differently.

Science

Science provides evidence-based knowledge of natural systems, offering explanations of environmental processes. Scientific findings often inform public understanding and can validate or challenge existing perspectives.

Scientific reports on climate change, for example, shape debates by providing measurable data that supports arguments for urgent policy action.

Laws

Laws represent formal rules established by governments. They codify acceptable behaviours and influence how individuals and organisations act toward the environment.

DEFINITION

Laws: Binding rules created by governing bodies that regulate conduct and enforce consequences for violations.

Environmental protection laws, such as bans on single-use plastics, alter perspectives by normalising sustainable practices.

Economics

Economics plays a central role in shaping perspectives by highlighting costs, benefits, and trade-offs. Economic incentives can influence whether people view environmental protection as viable.

For instance:

Subsidies for renewable energy foster support for green transitions.

Economic reliance on fossil fuels encourages resistance to environmental restrictions.

Events

Events, especially environmental disasters, can rapidly shift public perspectives. Oil spills, wildfires, or floods provide tangible experiences that change how people value ecological resilience.

Media coverage of events amplifies their influence, ensuring that awareness spreads beyond directly affected communities.

Values

Values underpin personal and collective decision-making. They influence what individuals and societies prioritise when considering environmental issues.

Values may emphasise economic growth, human well-being, or ecological preservation, leading to diverse perspectives.

Values underpin personal and collective decision-making.

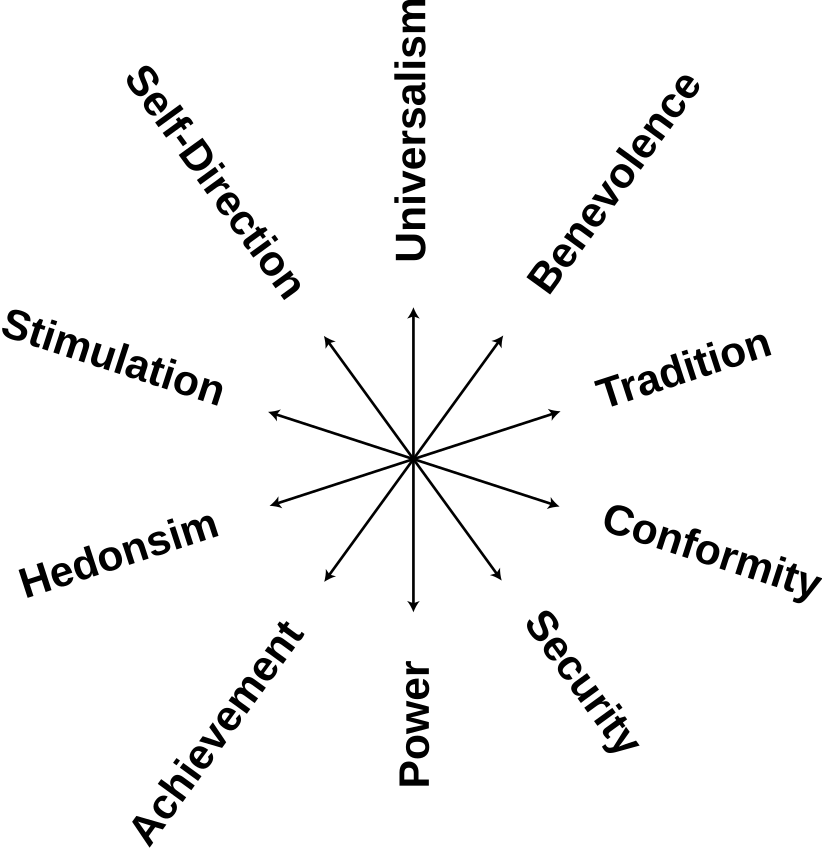

Circular diagram of the Schwartz basic human values, grouping ten value types around motivational continua (e.g., self-transcendence vs. self-enhancement). It illustrates how value emphases can steer environmental priorities and positions. The specific ten-value taxonomy exceeds syllabus requirements but clarifies the role of values. Source.

Lived Experience

Lived experience refers to the direct personal encounters individuals have with environmental issues. Farmers experiencing drought, for instance, may prioritise water conservation more than urban residents.

These experiences anchor abstract issues in reality, making perspectives more urgent and emotionally resonant.

From Perspectives to Positions and Actions

Positions

A position is the stance or viewpoint held in relation to an environmental issue. It reflects the combination of influences shaping an individual’s or group’s perspective.

Positions may include:

Support for stricter climate policies.

Opposition to renewable energy projects in local areas.

Advocacy for biodiversity conservation.

Actions

Actions are the behaviours or initiatives that follow from positions. They can be:

Personal actions, such as reducing energy use.

Community actions, like local recycling schemes.

Policy actions, including the implementation of environmental regulations.

The Role of Arguments

What Are Arguments?

Arguments provide the reasoning that supports or challenges a perspective. They connect evidence, values, and logic to justify why a position is valid or should be contested.

Arguments provide the reasoning that supports or challenges a perspective.

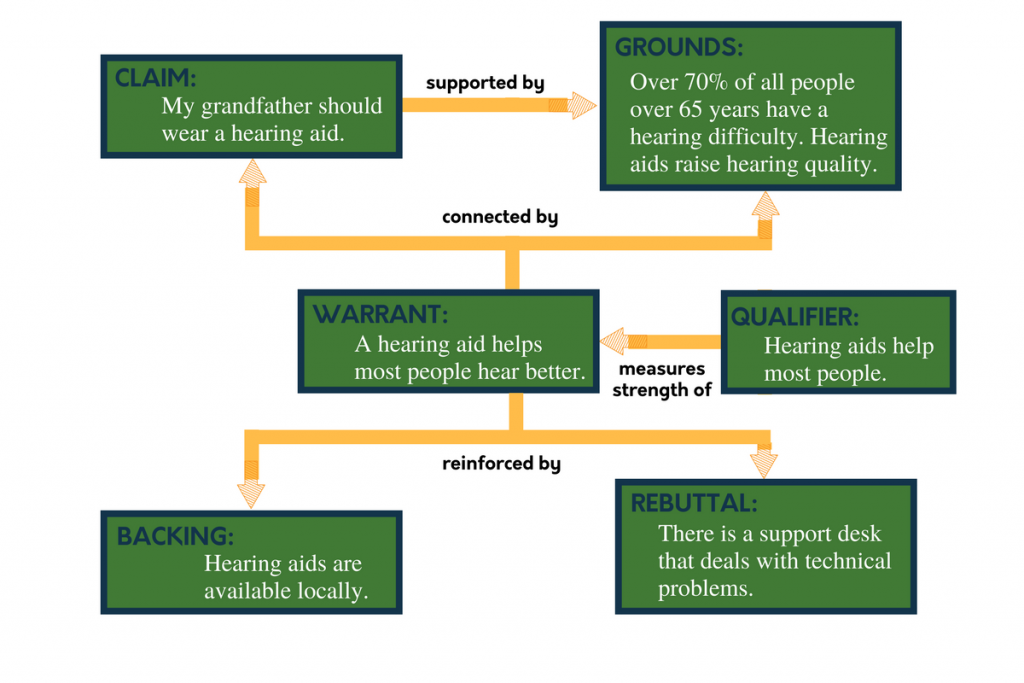

This diagram visualises the Toulmin structure of argument—linking claim, grounds (evidence), and warrant, with optional backing, qualifier, and rebuttal. It helps students analyse how reasons are organised to support or challenge a perspective. Elements such as “qualifier” and “rebuttal” extend beyond the minimum needed by the syllabus but aid critical evaluation. Source.

Arguments: Structured sets of reasons and evidence presented to support or oppose a particular perspective or position.

Arguments serve as tools of persuasion in environmental debates, policy-making, and scientific discussions.

Types of Arguments

Scientific arguments rely on data, research, and evidence.

Ethical arguments appeal to moral responsibility and fairness.

Economic arguments assess costs, benefits, and efficiency.

Political arguments emphasise governance, stability, and public opinion.

Supporting and Challenging Perspectives

Arguments can either reinforce existing perspectives or directly oppose them. For example:

Supportive: “Scientific evidence shows rising carbon emissions increase global warming; therefore, emissions reduction is essential.”

Challenging: “Economic development should not be constrained by emissions limits; technological innovation will provide solutions.”

Interactions Between Perspectives and Arguments

Dynamic Nature

Perspectives and arguments are not fixed. They shift with:

New scientific discoveries.

Changing laws or policies.

Evolving social norms.

Influential events that alter priorities.

Conflicts and Debates

When perspectives differ, arguments clash. Conflicts often occur between:

Economic growth advocates vs. environmental protection advocates.

Local communities vs. government planners.

Developed nations vs. developing nations in international negotiations.

Influence of Communication

Communication channels such as media, social networks, and education systems amplify perspectives and arguments, increasing their reach and impact.

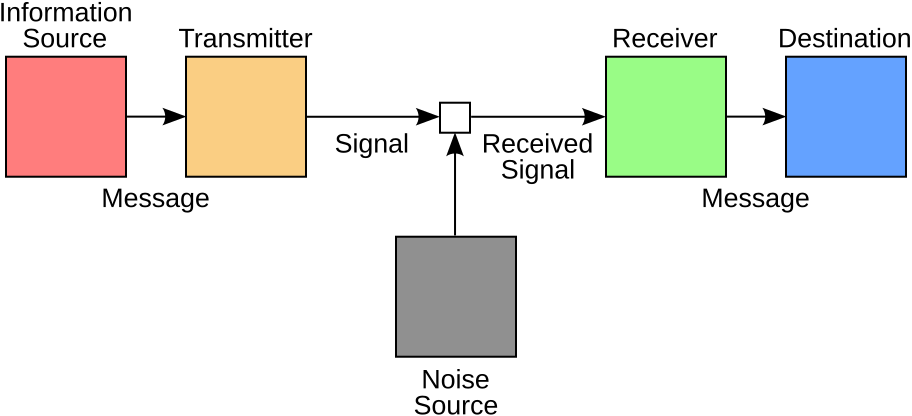

A schematic of the Shannon–Weaver communication model showing source, encoder, channel (with noise), decoder, and receiver. It clarifies how messages that frame environmental perspectives travel through media and where distortion can occur. Labels match terminology commonly used in communication studies. Source.

Key Takeaways

Perspectives arise from norms, science, laws, economics, events, values, and lived experiences.

These influences shape positions and actions.

Arguments provide structured reasoning that supports or challenges perspectives.

Environmental debates involve an interplay of scientific, ethical, economic, and political arguments.

Perspectives evolve over time, driven by social, cultural, and environmental changes.

FAQ

Cultural traditions influence how communities view the environment by embedding long-standing practices and beliefs into daily life.

For example:

In some Indigenous societies, traditions emphasise spiritual connections with nature, supporting conservationist perspectives.

Industrialised societies may prioritise human progress and technological control, creating more anthropocentric outlooks.

These differences explain why environmental policies often face varied acceptance globally.

Economic arguments directly affect livelihoods, making them highly persuasive in discussions about environmental issues.

They appeal to:

Cost savings, such as energy efficiency reducing household bills.

Job creation, where green industries are presented as growth opportunities.

Trade-offs, highlighting the risks of economic losses from environmental damage.

This focus on tangible impacts makes economics a strong driver in shaping public and political perspectives.

Education introduces young people to scientific evidence, ethical reasoning, and cultural narratives about the environment.

Curricula that stress sustainability encourage ecocentric perspectives.

Schools in resource-dependent regions may focus more on economic development, fostering anthropocentric views.

Education also shapes the skills to evaluate arguments critically, making it a powerful tool for forming long-term perspectives.

Large-scale events often reframe arguments by providing immediate, shared experiences.

Examples include:

The Chernobyl disaster highlighting nuclear risks.

The 2019 Amazon wildfires sparking international debates on deforestation.

COVID-19 lockdowns raising arguments about air quality and reduced emissions.

These events bring urgency, altering both public expectations and political priorities within short timeframes.

Conflicting values create disagreements about priorities. For instance, valuing economic growth may clash with valuing ecological preservation.

Tensions arise because:

Policies often favour one value over another.

Stakeholders interpret risks differently.

Media and politics amplify opposing arguments.

This makes environmental debates complex, requiring negotiation and compromise between competing perspectives.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks):

Identify two factors that can shape an individual’s environmental perspective.

Mark Scheme:

1 mark for each correct factor, up to 2 marks.

Acceptable answers include: norms, science, laws, economics, events, values, lived experience.

Question 2 (5 marks):

Explain how values and lived experiences influence the positions and actions individuals or groups take on environmental issues.

Mark Scheme:

1 mark: Definition or clear description of values as guiding principles shaping judgements and priorities.

1 mark: Explanation of how values lead to different environmental positions (e.g., prioritising economic growth vs. ecological preservation).

1 mark: Definition or description of lived experience as direct personal encounters with environmental issues.

1 mark: Explanation of how lived experiences affect urgency or emphasis in positions (e.g., farmers facing drought prioritising water conservation).

1 mark: Linking either values or lived experience to resulting actions (personal, community, or policy-level actions).