IB Syllabus focus:

‘Technocentrism trusts technology to solve environmental problems. Anthropocentrism centres human interests across diverse views. Ecocentrism assigns intrinsic value to nature. These categories are useful but overlap and change with context; individuals often hold mixed positions.’

Environmental perspectives guide how societies respond to ecological challenges. Understanding technocentric, anthropocentric, and ecocentric perspectives helps students interpret decision-making, policies, and behaviours shaping sustainable futures across varying contexts.

Technocentric Perspective

Core Characteristics

A technocentric perspective emphasises human innovation and the capacity of technology to overcome environmental challenges. It reflects confidence in human ingenuity and scientific progress.

Technocentrism: The belief that technology and human innovation can resolve environmental issues, often prioritising economic growth and human advancement.

Key Features

Strong trust in technological solutions (e.g., renewable energy, carbon capture, genetic engineering).

Emphasis on economic growth as compatible with environmental protection.

Confidence in scientific research and policy-driven innovation.

Tendency to prioritise human control over nature rather than natural self-regulation.

Examples

Large-scale geoengineering projects to combat climate change.

Expansion of nuclear power to provide low-carbon energy.

Agricultural biotechnology for enhanced crop yields and resistance.

Criticisms

Over-reliance on untested or expensive technologies.

Possible neglect of underlying ecological or social causes of problems.

Risks of unforeseen consequences from large-scale interventions.

Technocentrism trusts technology to solve environmental problems.

Utility-scale photovoltaic arrays illustrate a technocentric approach: environmental quality is pursued through engineered energy systems that displace fossil fuels and reduce emissions. The image shows ordered rows of panels and service roads characteristic of industrial solar design. Source.

Anthropocentric Perspective

Core Characteristics

The anthropocentric perspective places human interests at the centre of environmental decision-making. It represents a spectrum of views, from those prioritising short-term human gain to those advocating responsible stewardship.

DEFINITION

Anthropocentrism: The perspective that humans are the central and most significant species, and that environmental management should prioritise human needs and interests.

Key Features

Values the environment primarily for its utility to humans.

Promotes sustainable management of resources for long-term benefit.

Policies often guided by laws, economics, and ethics rather than ecological limits alone.

Can include stewardship models, where humans are caretakers of the planet.

Examples

International agreements balancing development with emission reductions.

Government regulation of deforestation for sustained timber use.

Water management schemes prioritising agricultural and urban demand.

Criticisms

May undervalue ecosystems without direct human benefit.

Risk of overexploitation if human interests consistently outweigh ecological concerns.

Can lead to anthropogenic bias in research and policymaking.

Anthropocentrism centres human interests across diverse views.

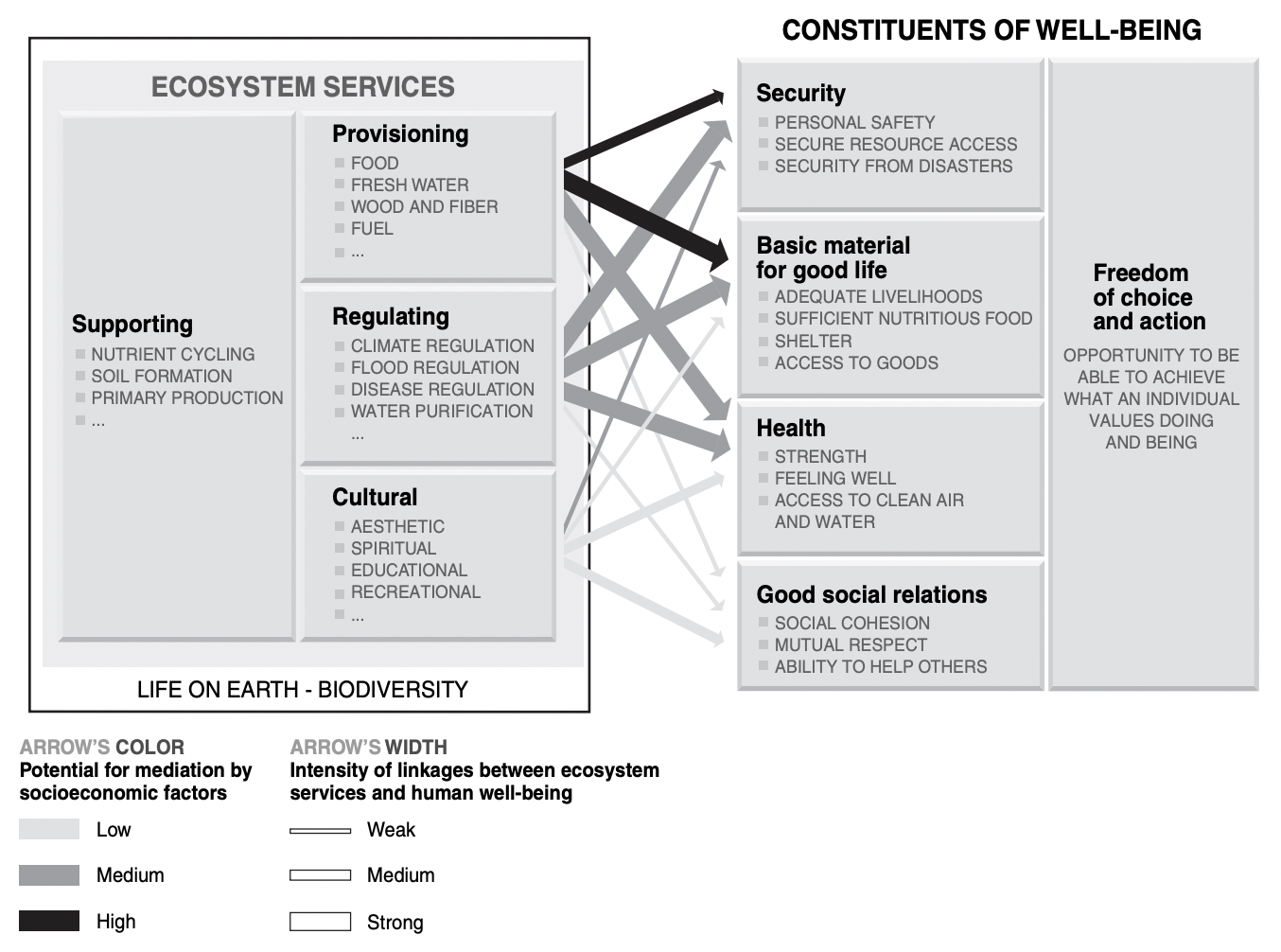

This diagram from the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment highlights how ecosystem services connect to human well-being, reflecting an anthropocentric lens. It includes extra detail (arrow widths/colours for linkage strength and mediation) not required by the syllabus but helpful for context. Source.

Ecocentric Perspective

Core Characteristics

An ecocentric perspective assigns intrinsic value to nature, recognising the rights of ecosystems, species, and landscapes to exist independently of human use.

Ecocentrism: The worldview that nature has inherent worth and should be preserved for its own sake, regardless of human benefit.

Key Features

Prioritises ecosystem integrity over human exploitation.

Advocates for minimal interference in natural processes.

Supports conservation of species and habitats even without economic rationale.

Often aligned with deep ecology and biocentric philosophies.

Examples

Campaigns to protect endangered species regardless of economic value.

Creation of wilderness reserves with strict human access limits.

Recognition of rivers or ecosystems as legal entities with rights.

Criticisms

May conflict with urgent human needs, particularly in developing countries.

Can be seen as impractical in globalised economies reliant on natural resource extraction.

Difficult to apply consistently in policymaking.

Ecocentrism assigns intrinsic value to nature.

Wilderness designation reflects an ecocentric perspective: ecosystems are conserved primarily for their intrinsic value. Such protection typically restricts roads, mechanised access, and resource extraction to maintain natural processes. Source.

Overlaps, Contexts, and Mixed Positions

Blurring of Boundaries

While these categories are useful for analysis, individuals and societies often adopt mixed perspectives depending on context. For instance:

A government might promote technocentric solutions like solar farms while also enforcing anthropocentric laws on water management.

An individual may recycle (technocentric and anthropocentric motivation) while also supporting ecocentric biodiversity conservation.

Contextual Influences

Perspectives can shift due to:

Cultural values shaping collective priorities.

Religious beliefs influencing environmental ethics.

Political ideologies framing the role of markets and governments.

Scientific discoveries altering public understanding of ecological limits.

Importance in Environmental Systems and Societies

Helps explain conflicts between groups with different worldviews (e.g., conservationists vs industrial developers).

Provides insight into policy debates and the design of sustainability strategies.

Encourages students to critically assess their own perspectives and biases.

Comparative Overview

Technocentric

Human innovation as the key driver.

Trust in science and technology.

Risks overconfidence in engineered solutions.

Anthropocentric

Human needs central, environment valued for utility.

Balances exploitation and stewardship.

Risks undervaluing ecosystems lacking direct human use.

Ecocentric

Nature valued for its own sake.

Advocates preservation and minimal interference.

Risks impracticality in human-dominated systems.

FAQ

Technocentrism encourages investment in large-scale technologies like wind farms, solar arrays, and hydroelectric dams. The focus is on innovation to reduce dependency on fossil fuels.

This perspective often supports policies that fund research, provide subsidies for renewable energy, and promote international collaboration in energy technology.

Cultural values determine how societies balance human needs with environmental care.

In industrialised nations, anthropocentrism may stress economic growth alongside environmental regulation.

In agrarian societies, it may prioritise water or land use to sustain livelihoods.

Religion and traditions can reinforce stewardship models, framing humans as caretakers.

Ecocentric perspectives challenge dominant economic models by insisting nature has rights independent of human needs.

This can lead to calls for halting resource extraction entirely, banning development in sensitive ecosystems, or granting legal rights to rivers and forests.

Such positions often clash with governments prioritising growth, making them appear radical within mainstream policy debates.

Yes, perspectives are not fixed categories. Individuals may shift depending on context.

For example, someone may support renewable technology (technocentric), believe in sustainable logging (anthropocentric), and also back wildlife conservation (ecocentric).

Mixed perspectives show how environmental decision-making often blends values rather than fitting neatly into one model.

Movements often combine perspectives to appeal to wider audiences.

Climate action campaigns may highlight technological solutions (technocentric).

Sustainable development groups may focus on balancing human needs (anthropocentric).

Biodiversity campaigns often stress nature’s inherent worth (ecocentric).

By blending perspectives, movements can build broader support and achieve greater influence in international policy.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Define ecocentrism and explain how it differs from technocentrism.

Mark scheme:

1 mark: Correct definition of ecocentrism (nature has intrinsic value, preserved for its own sake, minimal human interference).

1 mark: Clear distinction from technocentrism (technology and human innovation as primary solutions, prioritising human control).

Question 2 (6 marks)

Discuss how technocentric, anthropocentric, and ecocentric perspectives might lead to different policy decisions regarding deforestation.

Mark scheme:

1 mark: Identification of a technocentric approach (e.g., using technology such as reforestation drones, genetically engineered fast-growing trees).

1 mark: Explanation of how this reflects reliance on human innovation to solve environmental problems.

1 mark: Identification of an anthropocentric approach (e.g., sustainable forest management balancing timber use and economic needs).

1 mark: Explanation of how this reflects prioritisation of human benefits and long-term management.

1 mark: Identification of an ecocentric approach (e.g., strict protection of forests, designating them as conservation areas regardless of human utility).

1 mark: Explanation of how this reflects valuing nature’s intrinsic worth and maintaining ecosystem integrity.