IB Syllabus focus:

‘Invasives arrive via trade, travel, or releases; they reduce biodiversity through competition, predation, and pathogens. Use local examples and management strategies to mitigate impacts.’

Invasive species threaten global biodiversity by spreading through human activities such as trade and travel. Their impacts disrupt ecosystems, requiring targeted management strategies to minimise long-term ecological damage.

Pathways of Invasive Species

Human-Mediated Pathways

Invasive species often spread unintentionally through globalisation. Increased movement of goods and people provides opportunities for organisms to cross natural barriers.

Ballast water released by ships can contain plankton, larvae, and pathogens transported across biogeographical boundaries, seeding invasions in new harbours. Managing ballast water is a core prevention measure in biosecurity for marine systems. This real-world image illustrates a key pathway emphasised in the syllabus. Source.

Trade and transport: Shipping containers, ballast water, and timber transport can harbour pests, seeds, or aquatic organisms.

Travel and tourism: Hikers, vehicles, and luggage can transport seeds, insects, or pathogens to new regions.

Pet and ornamental trade: Exotic pets or garden plants may escape or be released into the wild, establishing self-sustaining populations.

Intentional Introductions

Not all introductions are accidental. Some species are deliberately moved for agriculture, forestry, or pest control but later become invasive. Examples include:

Rabbits introduced into Australia for hunting, which devastated vegetation.

Kudzu vine in the United States, promoted for erosion control, later overran landscapes.

Natural Spread After Introduction

Once established, invasive species can disperse rapidly. Birds, rivers, and wind can carry seeds or spores beyond the initial point of entry, expanding their ecological footprint.

Invasive Species: Non-native organisms introduced to a new ecosystem that establish, spread, and cause environmental, economic, or social harm.

Impacts of Invasive Species

Competition

Invasive species often outcompete native species for resources. For example, the grey squirrel in the UK displaced the native red squirrel by monopolising food sources and spreading disease.

Predation

Introduced predators may devastate local prey populations that lack evolutionary defences. A notable case is the brown tree snake in Guam, which caused the extinction of several native bird species.

Pathogens and Disease

Invasive species may introduce or amplify pathogens. For instance, chytrid fungus spread globally through amphibian trade, driving severe amphibian declines.

Ecosystem-Level Effects

Beyond individual species impacts, invasives can alter entire ecosystems:

Changing nutrient cycles (e.g., nitrogen-fixing plants in nutrient-poor soils).

Increasing fire frequency (e.g., invasive grasses creating more flammable conditions).

Altering hydrology (e.g., saltcedar trees increasing water loss from rivers in arid regions).

Control and Management Strategies

Prevention and Biosecurity

The most effective management occurs before species establish. Strategies include:

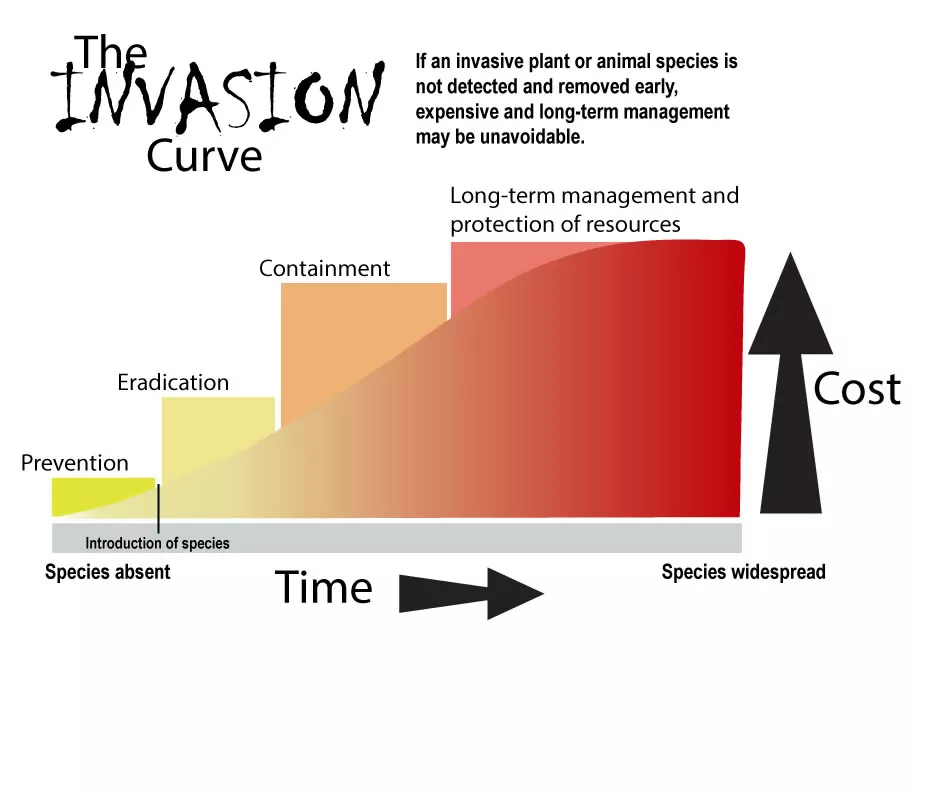

The invasion curve shows that costs rise and the likelihood of eradication falls as an invasive species spreads, highlighting the value of prevention, early detection and rapid response. This conceptual graphic underpins biosecurity programmes and guides resource allocation. The figure includes generalised phases of invasion; details may exceed the minimal syllabus scope but directly support control principles. Source.

Quarantine checks at ports of entry.

Cleaning protocols for ships and aircraft.

Public education campaigns discouraging exotic pet releases.

Early Detection and Rapid Response

Monitoring programmes and citizen science projects improve detection. If invasives are spotted early, eradication may be feasible through:

Manual removal (weeding invasive plants).

Targeted trapping (e.g., rodents on islands).

Pesticide use under controlled conditions.

Long-Term Control

For species already established, management shifts to containment and control:

Biological control: Introducing natural predators or pathogens (e.g., ladybirds to control aphids).

Mechanical control: Cutting, burning, or dredging invasive plants.

Chemical control: Herbicides or insecticides, used with caution to avoid harming native species.

Ecological Restoration

Removing invasives often requires follow-up actions. Restoring native vegetation, reintroducing native species, and managing habitats ensures invasives do not simply return.

Biological Control: The use of a species’ natural predators, parasites, or diseases to reduce its population in a non-native habitat.

Case Study Examples

New Zealand – Stoats and Birds

Stoats, introduced for rodent control, predated heavily on ground-nesting birds such as the kiwi. Ecosanctuaries with predator-proof fencing now provide safe zones for vulnerable species.

Predator-proof fences exclude invasive mammals such as stoats, rats and cats, allowing native populations to recover behind the barrier. Design features include curved caps and buried mesh to prevent climbing and burrowing. This is a widely used control tool in New Zealand ecosanctuaries. Source.

United Kingdom – Japanese Knotweed

Introduced as an ornamental plant, Japanese knotweed spread aggressively, damaging infrastructure and ecosystems. Control efforts combine mechanical removal and herbicide treatment, with research into specialised biological control agents.

Lake Victoria – Nile Perch

Introduced for fishing, the Nile perch caused massive declines in native cichlid diversity. While economically beneficial, its presence has permanently reshaped aquatic food webs.

Challenges in Invasive Species Management

Cost: Eradication and control programmes require sustained funding.

Public perception: Some invasives are culturally valued (e.g., introduced deer for hunting).

Ecological complexity: Removing one invasive may lead to unintended consequences, such as the rise of another pest species.

Global change: Climate change and continued trade increase the likelihood of invasions, creating moving targets for management.

Biosecurity: A set of preventive measures designed to reduce the risk of transmission of invasive species, pests, or diseases into new environments.

Integrated Approach

Most successful management combines prevention, monitoring, eradication, and long-term restoration, adapted to local conditions. Partnerships among governments, NGOs, and local communities are essential to coordinate efforts and share resources.

FAQ

Successful invasive species often share traits such as rapid reproduction, broad diet, tolerance to a wide range of conditions, and a lack of natural predators in the new environment.

Many invasive plants produce abundant seeds, while animals may have high breeding rates. Generalist feeding behaviour allows them to exploit diverse resources, outcompeting natives.

Invasive species can reduce the benefits ecosystems provide to humans. For example, invasive plants may deplete water supplies, while invasive insects damage crops.

Key services affected include:

Provisioning (loss of fisheries, timber, or medicinal plants)

Regulating (reduced water purification, altered fire regimes)

Cultural (decline in iconic or culturally significant species)

Island ecosystems often contain species that evolved in isolation without strong predators or competitors. This makes them less resilient to invasions.

For example, ground-nesting birds on islands are highly vulnerable to introduced mammals like rats or cats, which cause rapid declines and extinctions.

Climate change can expand the potential range of invasives by creating warmer or wetter conditions. Species once limited to tropical zones may now survive in temperate regions.

Shifts in rainfall or temperature may also stress native species, making ecosystems less competitive and more vulnerable to invasion.

Agreements aim to coordinate biosecurity across borders. The International Maritime Organization regulates ballast water discharge, while CITES limits trade in potentially harmful species.

Regional agreements often focus on shared ecosystems, such as the European Union’s regulation on invasive alien species, which requires member states to prevent, monitor, and manage priority species.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Identify two human-mediated pathways through which invasive species can be introduced into new ecosystems.

Mark Scheme:

1 mark for each correct pathway identified (any two of the following):

Trade and transport (e.g., ballast water, shipping containers, timber)

Travel and tourism (e.g., seeds carried on luggage, vehicles, clothing)

Pet and ornamental trade (e.g., escaped exotic pets, garden plants released into the wild)

Question 2 (5 marks)

Explain how invasive species can reduce biodiversity, and describe two strategies used to control their impacts.

Mark Scheme:

Up to 2 marks for explanation of biodiversity reduction:

Outcompete native species for food, space, or light (1 mark).

Introduced predators or pathogens reducing native populations (1 mark).

Alteration of ecosystem processes such as nutrient cycling, fire frequency, or hydrology (1 mark, maximum 2 overall for this section).

Up to 3 marks for control strategies:

Prevention and biosecurity measures such as port checks, cleaning protocols, or public education (1 mark).

Early detection and rapid response, e.g., manual removal, targeted trapping, pesticide use (1 mark).

Long-term control through biological, mechanical, or chemical methods (1 mark).

Ecological restoration after invasive removal (1 mark, but only two strategies credited).

Maximum 5 marks in total.