IB Syllabus focus:

‘Listing publicizes vulnerability and guides governments, NGOs and citizens in setting priorities and selecting management strategies, reflecting different perspectives and constraints.’

Biodiversity assessments are critical tools for shaping conservation priorities, transforming species status evaluations into strategies that balance ecological needs, societal values, and practical constraints across global and local contexts.

Linking Status to Action

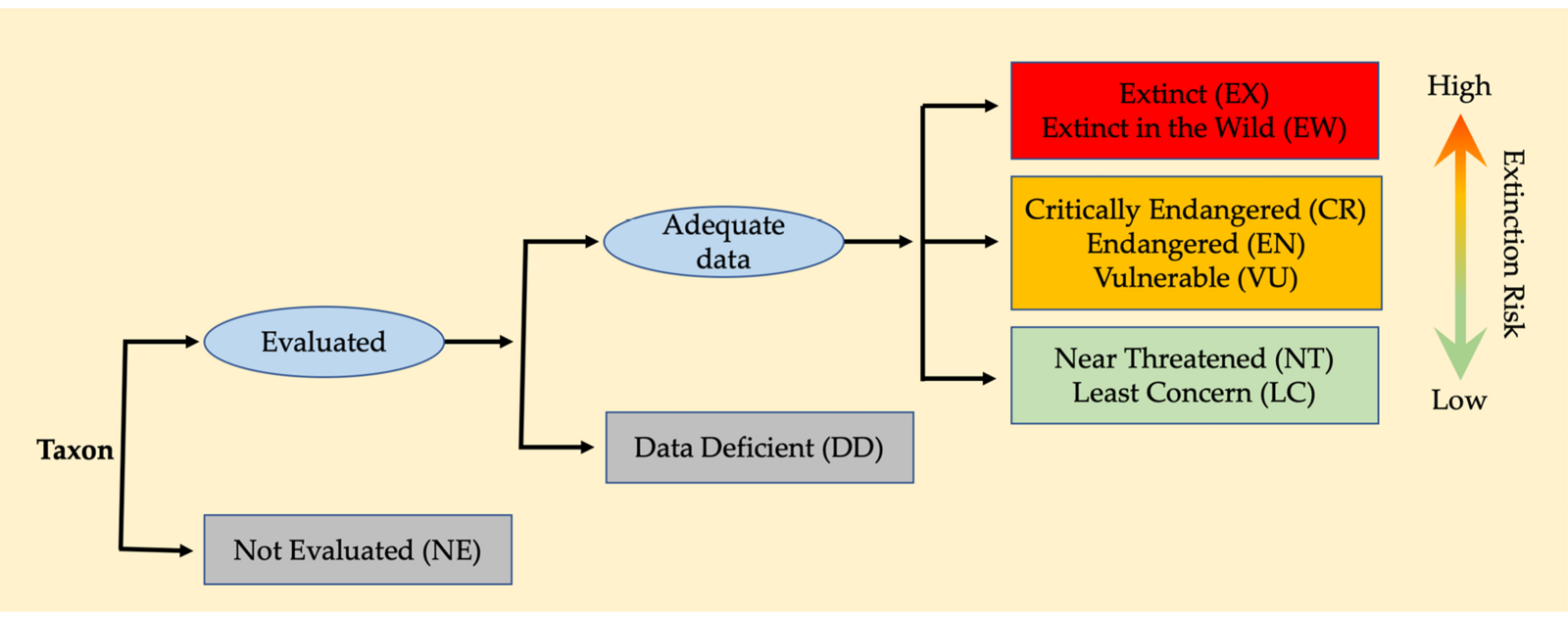

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List categorises species based on their extinction risk, ranging from Least Concern to Extinct. Once a species’ status is determined, this information does not remain static; it serves as a foundation for action. By publicising species’ vulnerability, the Red List raises awareness and mobilises decision-makers to direct limited resources where they are most needed.

Flow diagram illustrating the IUCN Red List categories and their relationships for evaluated species, including Least Concern, Near Threatened, Vulnerable, Endangered, Critically Endangered, Extinct in the Wild, Extinct, and Data Deficient. This visual supports how formal status underpins priority setting and conservation responses. Source.

Conservation Priorities and Their Importance

Establishing conservation priorities ensures that limited financial, political, and human resources are allocated effectively. Priorities typically focus on:

Preventing extinction of critically endangered species.

Protecting keystone species, whose roles maintain ecosystem structure.

Safeguarding endemic species, which are restricted to one region.

Preserving species of cultural, economic, or ecological significance.

By ranking needs, conservationists avoid spreading efforts too thinly, instead focusing on projects where interventions have the greatest ecological and societal impact.

Stakeholders in Conservation Decisions

Different actors interpret and use biodiversity status differently:

Governments

Governments rely on species assessments to justify legislation such as creating protected areas, enforcing bans on trade, or regulating land use. Priorities may reflect national interests, political agendas, or international obligations.

Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs)

NGOs often champion species that act as flagship species—well-known organisms that attract funding and public support. Their strategies may prioritise visibility and fundraising potential alongside ecological need.

Local Communities

For local people, conservation priorities intersect with livelihoods. A species seen as a crop pest may not be a local priority even if globally endangered, whereas culturally important species may attract stronger community support.

Citizens and Global Public

Citizen scientists contribute data collection, while public interest drives funding and policy momentum. High-profile species often secure more attention than less charismatic but ecologically vital organisms.

Balancing Perspectives and Constraints

Conservation decision-making is rarely straightforward, requiring trade-offs between competing values and limited resources.

Ecological perspective: Focuses on maintaining biodiversity, resilience, and ecosystem services.

Economic perspective: Considers costs, funding availability, and potential returns such as ecotourism.

Ethical perspective: Emphasises intrinsic value of all species, advocating protection regardless of economic benefit.

Social perspective: Prioritises human well-being, equity, and cultural values in conservation decisions.

Constraints include limited funding, political will, scientific uncertainty, and conflicts between conservation and development goals.

Processes for Setting Priorities

Once species status is determined, structured processes guide how priorities are set. These often involve:

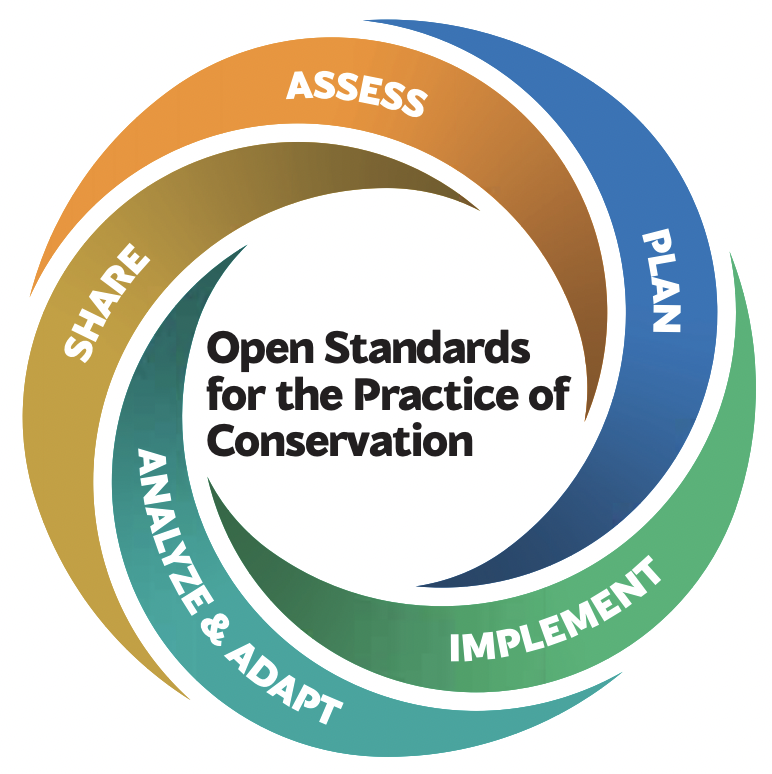

The Conservation Standards process wheel depicts an iterative cycle linking Assess, Plan, Implement, and Analyse & Adapt, with ongoing sharing of learning. It illustrates how status information is converted into strategies, actions, and feedback, aligning with adaptive priority setting. Source.

Risk assessment: Evaluating the likelihood of extinction.

Feasibility analysis: Assessing whether conservation interventions are practical and affordable.

Cost–benefit analysis: Balancing ecological gain against economic cost.

Stakeholder consultation: Engaging governments, NGOs, communities, and scientists.

Case Dimensions of Priority Setting

Example 1: Charismatic Species Bias

Charismatic species such as tigers or pandas often receive disproportionate funding. While effective for awareness, this may divert resources from less visible but ecologically essential organisms like amphibians.

Example 2: Global vs Local Perspectives

A globally endangered migratory bird may be common in one country but rare elsewhere. National governments may not prioritise it, while international treaties urge action.

Example 3: Socio-Economic Constraints

In developing regions, conservation strategies may conflict with urgent human needs such as agriculture or infrastructure. Decision-makers must weigh biodiversity value against social and economic pressures.

Conservation Priority: The process of ranking species, habitats, or ecosystems in order of importance for protection, based on ecological need, extinction risk, and social context.

Tools for Translating Status into Priorities

Conservationists use a range of tools to bridge the gap between species assessment and practical action:

Protected area designation: Establishing reserves for the most vulnerable species.

Restoration projects: Directing efforts toward habitats critical for threatened organisms.

Species action plans: Targeted interventions for those in greatest need.

Funding mechanisms: Prioritising grants and donor support toward high-risk categories.

Influence of Worldviews

Different environmental value systems shape conservation priorities.

Ecocentric worldviews: Emphasise intrinsic value of all life, prioritising broad ecosystem protection.

Anthropocentric worldviews: Focus on species providing direct benefits to humans.

Technocentric worldviews: Place confidence in technology to mitigate biodiversity loss, sometimes lowering urgency for immediate conservation action.

These differing views influence whether resources are directed to charismatic megafauna, ecosystem-wide protection, or species with direct economic importance.

Monitoring Success and Adjusting Priorities

Setting priorities is not a one-time process. Conservation outcomes must be evaluated against goals, and strategies adapted over time. A species’ status may improve (e.g., moving from Critically Endangered to Endangered) or worsen, requiring shifts in resource allocation. Monitoring ensures accountability and efficient use of scarce conservation funding.

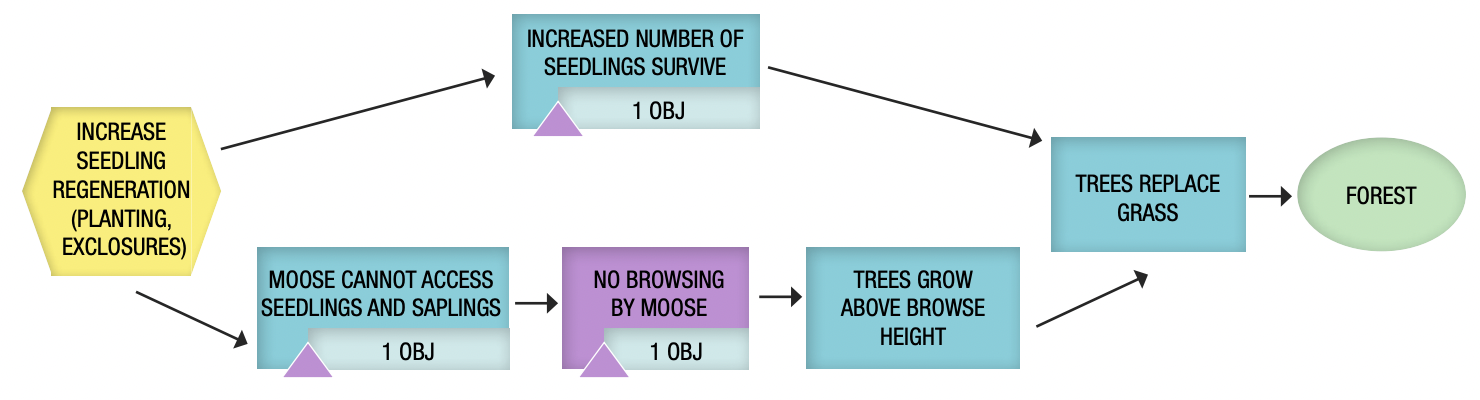

An example results chain shows how a selected strategy leads to intermediate results, threat reduction outcomes, and ultimately the conservation target, enabling objective monitoring and re-prioritisation. Although the example uses a moose–forest context, the causal structure generalises to any species or system. Source.

FAQ

The IUCN Red List provides a global assessment of species, while national red lists apply the same methodology within a single country.

National lists often highlight locally threatened species that may not appear globally endangered, ensuring conservation priorities reflect regional biodiversity and political contexts.

Endemic species are found only in a specific area, meaning their extinction results in global loss.

Prioritising them protects unique biodiversity and often secures specialised habitats that support other organisms. This makes endemic conservation highly efficient for maintaining ecosystem integrity.

Flagship species attract public interest and funding, serving as symbols for broader conservation goals.

Example: Giant pandas generate resources that support entire forest ecosystems.

However, focusing on flagships may neglect less charismatic but ecologically crucial species such as amphibians or invertebrates.

Cost–benefit analysis weighs ecological gains against economic expenditure.

High-cost projects with limited impact may be deprioritised.

Low-cost, high-impact measures, such as habitat corridors, often rise in priority.

This process ensures efficient resource use but may undervalue species with limited economic benefit.

When a species improves (e.g., from Endangered to Vulnerable), resources may shift towards those still at critical risk.

If a species worsens, urgent measures like ex situ conservation or emergency funding may be activated.

This adaptive approach ensures dynamic alignment between conservation goals and changing ecological realities.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

State two ways in which the IUCN Red List contributes to setting conservation priorities.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for each correct point, up to 2 marks total.

Possible answers include:Publicises the vulnerability of species to raise awareness. (1)

Provides an objective framework for governments and NGOs to allocate resources. (1)

Establishes categories that indicate urgency of conservation action. (1)

Guides the creation of species-specific management strategies. (1)

Question 2 (5 marks)

Discuss how different stakeholders (such as governments, NGOs, and local communities) may have conflicting perspectives when setting conservation priorities based on species’ status.

Mark scheme:

Explanation of at least two stakeholders’ perspectives required.

Balanced discussion of conflicts or trade-offs needed for full marks.

Award up to 5 marks as follows:

Identifies stakeholder group (e.g., governments, NGOs, local communities, citizens). (1 each, max 2)

Describes how each uses species status in decision-making (e.g., governments may legislate, NGOs may fundraise, communities may focus on livelihoods). (1 each, max 2)

Explains potential conflict/trade-off between perspectives (e.g., local needs vs global conservation goals, charismatic species vs ecologically important species). (1)

Total: 5 marks