IB Syllabus focus:

‘Shared, unrestricted resources risk overuse and pollution due to individual incentives. Use examples such as Grand Banks fisheries and ocean plastic gyres.’

The tragedy of the commons describes the conflict between individual self-interest and collective well-being, where unrestricted access to shared resources leads to overuse, depletion, and environmental harm.

Understanding the Tragedy of the Commons

The tragedy of the commons is a concept widely applied in environmental science, economics, and resource management. It highlights the risks posed when common-pool resources (such as fisheries, pastures, forests, and oceans) are accessible to all without regulation.

Tragedy of the Commons: A situation where individuals, acting in their own self-interest, overexploit a shared resource, leading to long-term collective loss.

These resources are typically non-excludable (difficult to restrict access) but rivalrous (one user’s consumption reduces availability for others). This combination encourages short-term exploitation.

Key Features of the Tragedy

Individual Incentives

Individuals benefit by maximising their resource use — such as catching more fish or grazing more livestock. The personal gain is immediate, while the cost of depletion is shared among all.

Collective Loss

When many individuals act in this way simultaneously:

Resource stocks decline

Ecosystem resilience is reduced

Long-term sustainability is undermined

This mismatch between short-term gain and long-term loss is central to the tragedy.

Examples of the Tragedy

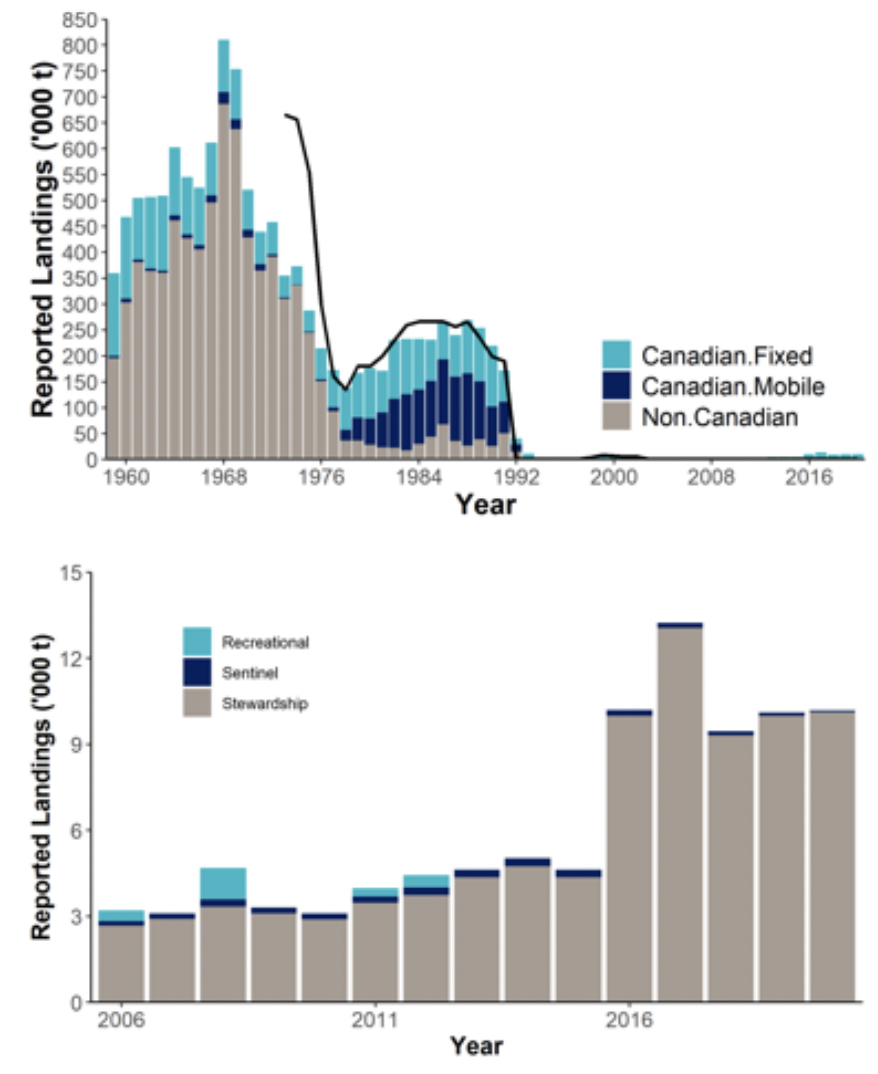

Grand Banks Fisheries

The Grand Banks off Newfoundland were once among the richest fishing grounds in the world. Advances in industrial fishing led to:

Massive overharvesting of cod

Population collapse in the early 1990s

Long-term bans on fishing, devastating local communities

This is a classic example of unregulated exploitation causing ecosystem collapse.

Reported Northern cod landings (1959–2020) with total allowable catches (TACs), showing high catches in the 1960s–1980s followed by collapse and a 1992 moratorium. The chart illustrates how individual incentives to maximise catch can deplete a shared stock when access is weakly regulated. Source.

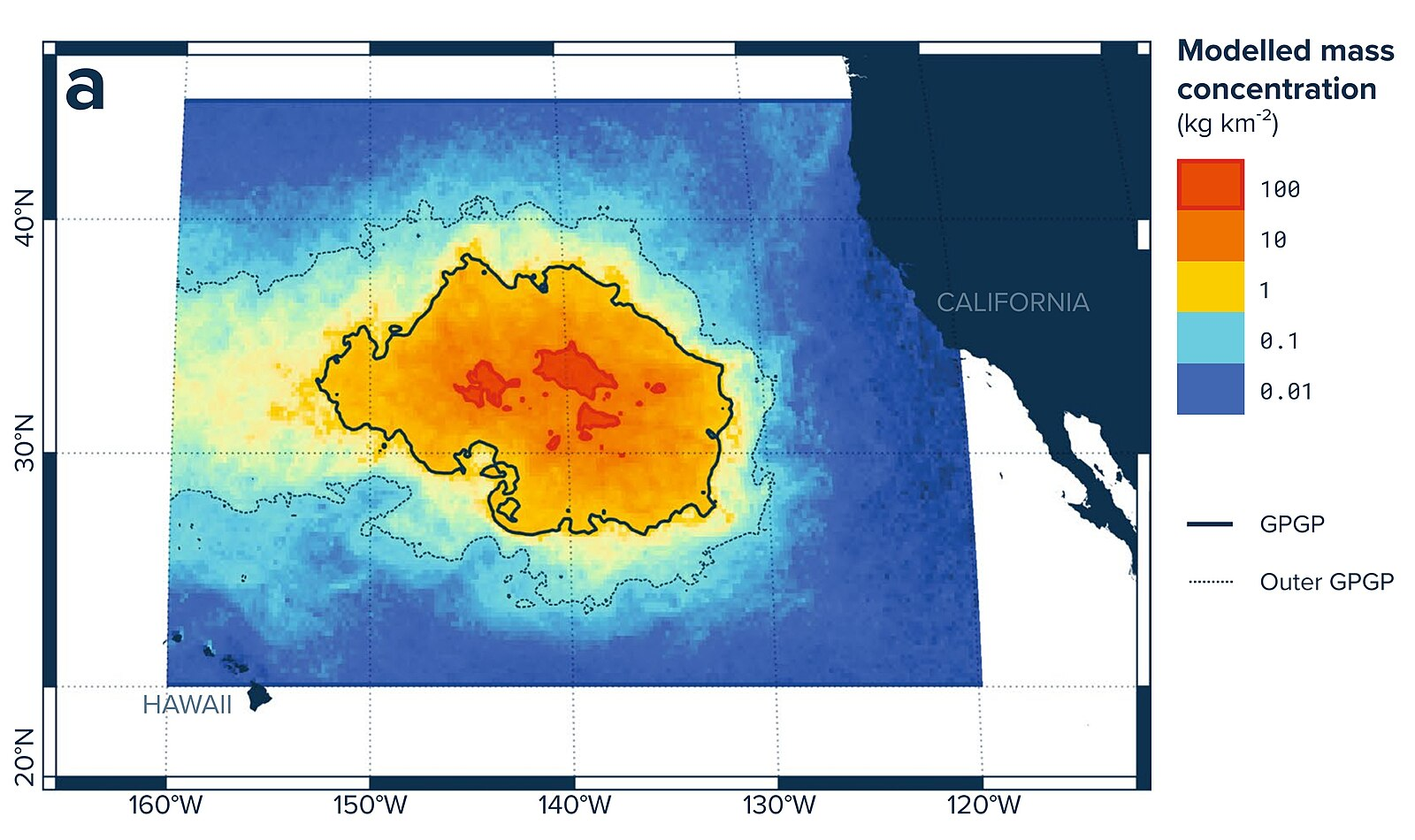

Ocean Plastic Gyres

The oceans act as a common sink for waste. With little regulation on global plastic use and disposal:

Plastics accumulate in gyres, such as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch

Marine ecosystems are harmed by ingestion and entanglement

Pollution persists for centuries

This demonstrates how pollution is also a tragedy of the commons.

Map of modelled plastic mass concentration in the North Pacific (August 2015), highlighting accumulation in the subtropical gyre known as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Warmer colours indicate higher mass concentrations; data are derived from a peer-reviewed analysis of floating debris. Source.

Mechanisms Driving the Tragedy

The tragedy arises from several interacting mechanisms:

Lack of property rights: No individual or group has ownership, so no one feels responsible.

Open access: Anyone can use the resource without restriction.

Short-term self-interest: Rational individuals seek immediate benefits.

Diffuse costs: The environmental and societal costs are shared widely, diluting responsibility.

Common-pool Resource: A resource that is non-excludable but rivalrous, such as fisheries, forests, and groundwater.

Consequences for Biodiversity

Unchecked use of commons can lead to:

Overexploitation of species (fish, timber, wildlife)

Habitat degradation (overgrazing, deforestation)

Pollution accumulation (plastics, greenhouse gases)

Loss of ecosystem services (carbon sequestration, soil fertility, clean water)

These impacts weaken biodiversity and ecosystem resilience, making recovery difficult.

Human Behaviour and the Commons

Humans often prioritise short-term economic survival or profit motives over long-term sustainability. Cultural and economic systems that value consumption and growth can worsen the tragedy. Without regulation, social norms alone are often insufficient to prevent exploitation.

Social Dilemmas

The tragedy is a social dilemma, where cooperation is needed but self-interest dominates. For example:

A fisherman reducing catch may lose income if others continue overfishing.

Communities dumping less waste may feel their efforts are insignificant if others persist.

Avoiding or Managing the Tragedy

Although the tragedy of the commons seems inevitable, strategies can reduce its impact. These include:

Regulation and Governance

Laws and quotas: Set sustainable limits on use (e.g., fishing quotas).

Protected areas: Restrict access to sensitive habitats.

Pollution controls: Limit emissions and waste disposal.

Community Management

Collective agreements: Local communities manage resources collaboratively.

Customary practices: Indigenous and traditional knowledge often sustain resources.

Economic Incentives

Taxes and subsidies: Discourage harmful practices and reward conservation.

Tradable permits: Limit total use while allowing market flexibility.

Education and Awareness

Raising awareness about sustainability fosters responsible consumption and increases public support for conservation measures.

Tragedy of the Commons in the Anthropocene

In the Anthropocene epoch, human impacts are unprecedented in scale. Shared resources such as:

The atmosphere (affected by greenhouse gas emissions)

The oceans (acidification, overfishing, plastics)

Biodiversity (declines across taxa)

are all at risk from collective misuse. This makes the tragedy of the commons a central challenge for global governance.

Key Takeaways

The tragedy of the commons arises when individual incentives conflict with collective sustainability.

Classic cases include the collapse of the Grand Banks fisheries and the growth of ocean plastic gyres.

Solutions require regulation, community cooperation, and education to balance short-term needs with long-term ecological resilience.

FAQ

It is a collective action problem because individuals acting rationally for personal benefit create outcomes harmful to the whole group. Each user benefits from exploiting more of the resource, but everyone suffers when it becomes depleted.

Without cooperation or regulation, there is little incentive for individuals to restrain use, even if they understand the long-term consequences.

Commons are especially vulnerable when they are:

Highly accessible, such as open seas or public pastures

Difficult to monitor, making regulation costly or ineffective

Slow to regenerate, like fish stocks or groundwater

Large in scale, meaning individual restraint has minimal visible effect

The combination of accessibility and limited oversight often determines the severity of overuse.

Cultural perspectives can reduce or exacerbate the tragedy. Communities with traditions of shared responsibility, taboos, or stewardship often manage commons sustainably.

Conversely, cultures emphasising economic growth and consumption may encourage exploitation without regard for long-term impacts. The strength of collective norms therefore shapes the likelihood of commons degradation.

Well-defined property rights create responsibility and accountability. When ownership or usage rights are assigned, individuals or groups have an incentive to conserve the resource for future benefit.

For example, community-managed forests with clear rights tend to have lower rates of deforestation than open-access forests. Conversely, absence of rights leaves resources vulnerable to unchecked exploitation.

Yes, technology can provide monitoring, enforcement, and substitutes.

Satellite tracking of fishing fleets helps detect illegal overfishing

Waste treatment and recycling reduce pollution burdens on shared sinks

Alternative materials, such as biodegradable plastics, lessen long-term accumulation in commons like oceans

While technology can reduce pressure, it requires governance and cooperation to be effective.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Define the term tragedy of the commons and give one example relevant to biodiversity or pollution.

Mark Scheme:

1 mark: Correct definition — individuals acting in their own self-interest overexploit a shared resource, leading to long-term collective loss.

1 mark: Suitable example such as Grand Banks fisheries collapse or accumulation of plastic in ocean gyres.

Question 2 (5 marks)

Explain how the tragedy of the commons can lead to biodiversity loss, using the Grand Banks fisheries as an example.

Mark Scheme:

1 mark: Identifies that the tragedy arises from unrestricted access to a shared resource (open access fishery).

1 mark: States that individual incentives encourage maximising catches for immediate personal gain.

1 mark: Explains that collective overfishing reduces fish stocks below sustainable levels.

1 mark: Links this to biodiversity loss — reduced populations, collapse of cod stocks, impacts on wider marine ecosystems.

1 mark: Provides detail from the Grand Banks case study (e.g., collapse in early 1990s, moratorium on cod fishing, long-term ecosystem impacts).