IB Syllabus focus:

‘Access to sufficient safe drinking water; a cornerstone of sustainable societies.’

Water security underpins social stability, economic growth, and ecological sustainability. Without secure access to safe water, societies face severe health, environmental, and developmental challenges.

Definition of Water Security

Water Security: Access to sufficient safe drinking water, which is considered essential for sustaining human life, health, and the functioning of sustainable societies.

Water security is not only about physical availability but also about the quality, safety, and reliability of water. This concept is central to the IB Environmental Systems and Societies syllabus because it links environmental processes to social and economic systems.

A Venn diagram shows sustainability as the overlap of environmental, economic and social domains, clarifying why water security underpins each pillar. This general sustainability framework provides context and does not add technical detail beyond the IB scope for this subsubtopic. Source.

Importance of Water Security

Human Health and Survival

Clean drinking water prevents waterborne diseases such as cholera, typhoid, and diarrhoea.

Lack of access can result in high infant mortality rates and reduced life expectancy.

Adequate water ensures basic hygiene practices, lowering the spread of infectious diseases.

Children collect water from a tap stand in a refugee settlement, illustrating how improved points of supply enable hygiene and reduce exposure to unsafe sources. The image focuses on access, not on water quality testing, which is addressed separately in monitoring frameworks. Source.

Social and Political Stability

Communities with water security are less vulnerable to conflicts over scarce resources.

Shared rivers and aquifers often require cooperative management to avoid international disputes.

Water scarcity can exacerbate existing social inequalities, disproportionately affecting marginalised groups.

Economic Development

Agriculture, which consumes most freshwater globally, depends on reliable water supplies for irrigation and livestock.

Industry needs water for cooling, processing, and production.

Tourism and recreation sectors rely on healthy aquatic systems, linking water security to broader economic opportunities.

Environmental Sustainability

Freshwater ecosystems such as wetlands, rivers, and lakes require adequate flows for biodiversity conservation.

Secure water resources help maintain ecosystem services such as nutrient cycling, flood regulation, and climate stabilisation.

Over-extraction can cause aquifer depletion, habitat loss, and declining water quality, undermining long-term sustainability.

Dimensions of Water Security

Availability

Water must be physically available from surface or groundwater sources in quantities sufficient to meet demand.

Accessibility

Water must be accessible to communities through infrastructure such as wells, pipes, and treatment facilities.

Quality

Water must be safe, free from harmful pathogens, pollutants, and toxins.

Reliability

Water access should remain stable over time, even during dry seasons or climate variability.

Threats to Water Security

Population Growth

Expanding populations increase demand for domestic, industrial, and agricultural water use.

Urbanisation places pressure on existing water infrastructure.

Climate Change

Alters rainfall patterns, leading to droughts, floods, and reduced snowpack.

Rising temperatures increase evaporation, reducing available freshwater.

Pollution

Industrial discharges, agricultural runoff, and sewage degrade water quality.

Contaminated water threatens both human health and aquatic ecosystems.

Overuse

Excessive irrigation and industrial withdrawal lower water tables.

Unsustainable extraction from rivers and aquifers reduces future availability.

Water Security and Sustainable Societies

Water security is a cornerstone of sustainable societies because it directly influences the three pillars of sustainability:

Environmental Sustainability

Maintains ecosystem health and biodiversity.

Ensures resilience to climate variability and extreme weather.

Economic Sustainability

Reliable water supplies support food production and industrial activity.

Prevents economic losses linked to droughts, floods, or degraded ecosystems.

Social Sustainability

Equitable access to water reduces inequality.

Supports human dignity, public health, and quality of life.

Global Perspective

Developed Countries

Typically have advanced infrastructure ensuring safe, reliable water supplies.

Challenges remain in maintaining quality and dealing with ageing systems.

Developing Countries

Struggle with limited infrastructure, contamination, and insufficient supply.

Rural communities often rely on unprotected sources, increasing health risks.

International Organisations

The United Nations recognises access to clean water and sanitation as a human right.

Agencies such as the World Health Organization (WHO) promote global water quality standards.

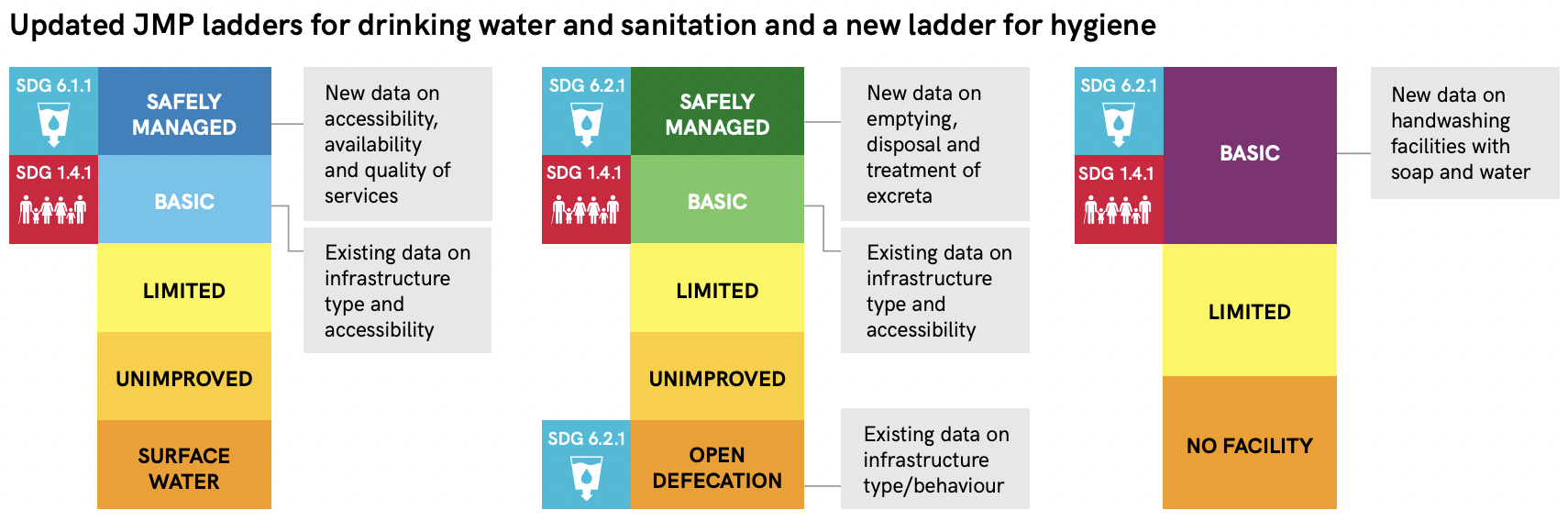

The JMP “service ladder” summarises drinking water service levels, highlighting the definition of safely managed services as accessible on premises, available when needed, and free from contamination. This figure also displays sanitation and hygiene ladders, which go beyond the scope of this subsubtopic but help to situate drinking water within WASH monitoring. Source.

Key Takeaways for IB ESS Students

Water security is more than just water availability; it includes safety, access, and reliability.

It underpins human health, social stability, economic growth, and environmental integrity.

Threats such as climate change, pollution, overuse, and population growth make water security a pressing global issue.

As a cornerstone of sustainable societies, ensuring water security requires integrated management of resources and cooperation at local, national, and international levels.

FAQ

The United Nations General Assembly in 2010 recognised access to safe and clean drinking water as a human right.

This means governments have a responsibility to ensure availability, accessibility, affordability, and quality. In practice, international law encourages states to integrate water security into policy frameworks and development programmes, especially in vulnerable regions.

Infrastructure is essential for transforming available water into secure supplies.

Storage: Dams and reservoirs stabilise supply across dry and wet seasons.

Treatment: Plants ensure water meets health standards.

Distribution: Pipes and pumping stations guarantee access within communities.

Without sufficient infrastructure, even regions with abundant water can face insecurity due to poor delivery.

In many developing regions, women and girls are responsible for water collection. Lack of secure access increases time burdens, limits education, and restricts employment opportunities.

Improved access through local taps or safe wells reduces these inequalities and promotes social sustainability.

Unreliable supply limits sanitation and hygiene practices.

Inconsistent flows disrupt handwashing and cleaning, allowing disease spread.

Healthcare facilities may struggle to sterilise equipment or maintain safe wards.

Thus, water security extends beyond consumption to wider health systems.

Shared rivers and aquifers can create tensions between states or communities when demand outpaces supply.

Disputes may arise over dam construction, diversion projects, or pollution. Conversely, cooperative management agreements can enhance regional stability and demonstrate how water security fosters peace.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Define the term water security as used in Environmental Systems and Societies.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying that water security means access to sufficient safe drinking water.

1 mark for recognising its importance to sustaining human health and functioning societies.

Question 2 (5 marks)

Explain why water security is considered a cornerstone of sustainable societies, with reference to at least two dimensions of sustainability.

Mark scheme:

Up to 2 marks for clear explanation of the link between water security and environmental sustainability (e.g., maintaining ecosystems, biodiversity, or resilience to climate variability).

Up to 2 marks for explanation of the link to economic sustainability (e.g., agriculture, industry, preventing economic losses).

Up to 2 marks for explanation of the link to social sustainability (e.g., equity, health, dignity, political stability).

Award a maximum of 5 marks.

Responses should cover at least two dimensions; partial credit given if only one is addressed fully.