IB Syllabus focus:

‘Climate change affects health, water, agriculture and infrastructure; vulnerabilities vary by socio-economic context. Local examples illustrate differential resilience.’

Climate change brings wide-ranging societal impacts, affecting essential systems like health, food, water, and infrastructure. These impacts vary greatly depending on local conditions, wealth, and preparedness.

Health Impacts of Climate Change

Direct health risks

Rising global temperatures and shifting weather patterns create several health challenges:

Heat stress: Increased frequency of heatwaves raises mortality, particularly among the elderly and those with pre-existing health conditions.

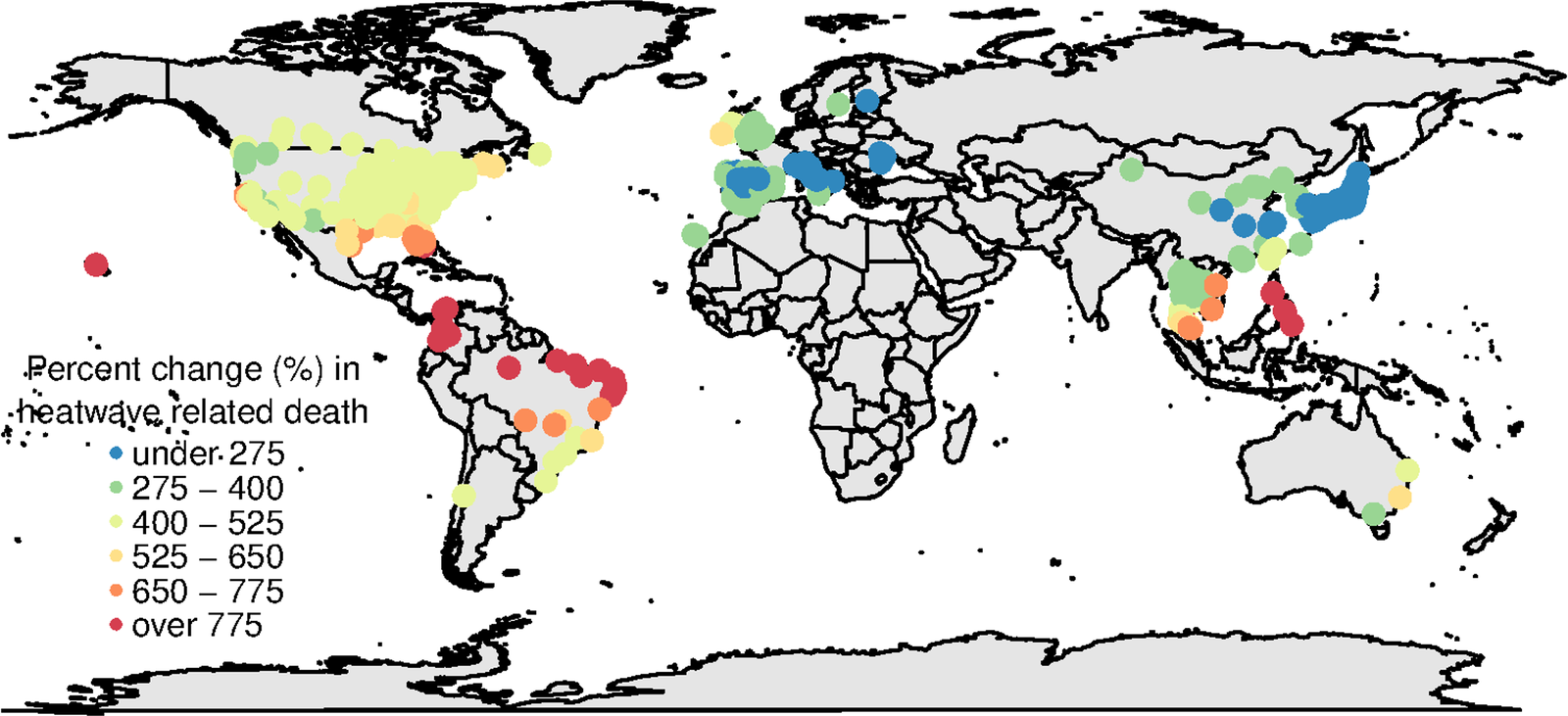

This map shows projected changes in heatwave-related excess mortality across multiple regions later this century, highlighting geographic differences in health risk. The scenario (RCP8.5, high-variant population, no adaptation) is an assumption set used to explore risk envelopes—extra detail beyond the IB specification but clarifying uncertainty. Use alongside teaching on adaptation and demographic vulnerability. Source.

Vector-borne diseases: Warmer temperatures expand the habitats of mosquitoes and ticks, increasing the spread of diseases such as malaria, dengue fever, and Lyme disease.

Respiratory problems: Higher concentrations of air pollutants and allergens worsen asthma and other respiratory conditions.

Indirect health risks

Water-borne diseases rise as floods contaminate drinking water.

Malnutrition results from reduced agricultural productivity, particularly in vulnerable regions.

Psychological stress increases following displacement, loss of livelihoods, and exposure to extreme weather.

Water Resources and Vulnerability

Availability and distribution

Climate change affects both the quantity and quality of freshwater.

Melting glaciers and altered rainfall patterns disrupt river flows and aquifers.

Droughts intensify in arid regions, increasing water scarcity.

Flooding events degrade water quality by introducing pollutants.

Regional contrasts

Wealthier nations can invest in desalination plants, advanced water treatment, or inter-basin transfers.

Poorer regions face limited adaptive capacity, increasing vulnerability to water insecurity.

Agriculture and Food Security

Crop yields

Temperature changes and shifts in precipitation reduce yields of key crops such as wheat, rice, and maize in many regions.

Pests and diseases spread into new areas, undermining productivity.

Some regions may temporarily benefit from longer growing seasons, particularly in temperate zones.

Food systems and livelihoods

Reduced yields cause food prices to rise, disproportionately affecting low-income populations.

Farmers reliant on subsistence agriculture are particularly vulnerable, with limited means to adapt.

Pastoral communities face overgrazing and desertification, threatening livestock and livelihoods.

Infrastructure and Urban Systems

Physical infrastructure

Flooding and storms damage roads, bridges, and power lines, leading to costly repairs.

Coastal cities face sea-level rise, which threatens ports, housing, and transport systems.

Heat extremes degrade building materials, railway tracks, and electricity grids.

Socio-economic consequences

Wealthier cities invest in climate-resilient infrastructure such as flood barriers and storm drains.

The Maeslantkering is a moveable storm-surge barrier that closes to protect Rotterdam from extreme sea levels, exemplifying large-scale structural adaptation. It demonstrates how engineered infrastructure can reduce exposure and protect critical economic assets in coastal cities. Use to contrast with community-level, nature-based measures discussed elsewhere. Source.

Poorer regions often lack resources, leaving populations more exposed to extreme events.

Differential Vulnerability

Socio-economic context

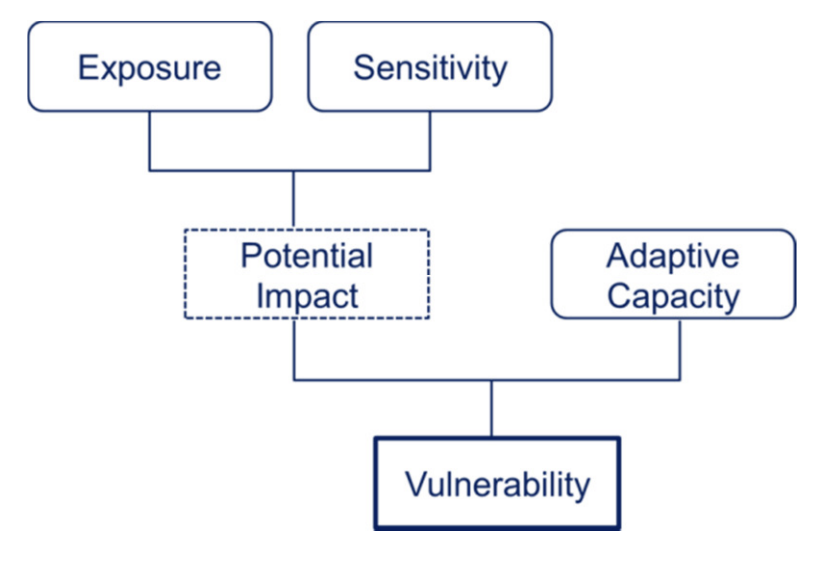

Vulnerability to climate change depends on exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity.

This diagram illustrates how exposure to climate hazards and societal sensitivity create potential impacts that can be reduced by adaptive capacity (institutions, technology, finance). It directly supports the triad used to explain why some communities experience greater harm from the same hazard. The figure’s generic layout suits IB-level conceptual understanding. Source.

High-income countries: Strong institutions, advanced technology, and financial resources improve resilience.

Low-income countries: Dependence on climate-sensitive sectors like agriculture, combined with weak governance and limited funding, heightens risk.

Local examples

Bangladesh: High exposure to cyclones and flooding but strong community-based adaptation measures, such as raised shelters, improve resilience.

The Netherlands: Wealth and technology enable advanced flood-defence systems, lowering vulnerability despite high exposure.

Ecosystem Services and Human Resilience

Healthy ecosystems provide natural protection for societies:

Mangroves protect coastal areas from storm surges.

Forests regulate water flows and reduce flood risks.

Wetlands filter water and support biodiversity.

Degraded ecosystems reduce resilience, compounding human vulnerability. Protecting ecosystem services is therefore crucial for long-term societal adaptation.

Building Resilience

Structural strategies

Building sea walls and flood defences in coastal zones.

Designing climate-resilient buildings with heat-resistant materials and elevated structures.

Expanding renewable energy to reduce reliance on fossil fuels and improve energy security.

Non-structural strategies

Education and awareness campaigns that inform communities about risks.

Early warning systems for extreme weather events.

Policy measures such as zoning laws, building codes, and insurance schemes.

Role of international cooperation

Global agreements like the Paris Agreement aim to reduce emissions and support adaptation, but implementation depends on national capacity and political will.

Key Definitions

Resilience: The capacity of a system, community, or society exposed to hazards to resist, absorb, adapt, and recover from their effects in a timely and efficient manner.

Vulnerability: The degree to which a system or community is susceptible to, or unable to cope with, adverse effects of climate change.

These concepts are central for understanding why some societies withstand climate impacts better than others.

Feedback Between Society and Climate

Societal responses can either strengthen or weaken resilience:

Positive feedbacks occur when poverty, environmental degradation, and weak institutions reinforce vulnerability.

Negative feedbacks emerge when strong adaptation reduces risks, allowing recovery and long-term stability.

Understanding these dynamics is essential for effective planning and adaptation policies.

FAQ

Climate change increases displacement by making areas uninhabitable due to flooding, desertification, or extreme heat. Rising sea levels threaten low-lying islands and coastal cities, forcing communities to migrate.

Displacement can be temporary, after disasters, or permanent when livelihoods collapse. Vulnerable groups often lack the resources to relocate safely, increasing risks of poverty and instability.

Inequality determines who has access to adaptation resources. Wealthier groups can afford insurance, relocation, or protective infrastructure, while poorer communities remain exposed.

Social inequality limits access to healthcare, education, and finance.

Gender inequality affects resilience, as women often have fewer resources in many societies.

This uneven distribution of risk deepens existing social divides.

Urban centres concentrate people, infrastructure, and economic activities, making them highly exposed to extreme events.

Heat islands amplify temperature-related health risks.

Dense populations increase the spread of water-borne and vector-borne diseases.

Critical infrastructure such as transport and power systems is more costly and complex to protect.

Large cities must invest heavily in adaptation strategies to remain resilient.

Indigenous and local knowledge can provide cost-effective strategies for resilience.

Traditional building methods, such as raised housing in flood-prone regions, reduce vulnerability.

Sustainable agricultural practices, like crop diversification and water harvesting, help communities adapt.

Community-based decision-making strengthens social networks that support recovery after disasters.

This knowledge complements scientific approaches and broadens adaptation options.

Not all impacts can be measured in monetary terms. Climate change affects cultural identity, heritage, and community cohesion.

Sacred sites and traditional lands may be lost to rising seas or desertification.

Forced migration disrupts cultural continuity and social bonds.

Mental health impacts, including eco-anxiety and trauma from disasters, alter community well-being.

These intangible effects highlight the broader societal costs of climate change.

Practice Questions

Question 2 (5 marks)

Explain why low-income countries are generally more vulnerable to the societal impacts of climate change than high-income countries.

Mark scheme:

Up to 2 marks for describing exposure and sensitivity in low-income countries.

e.g., reliance on climate-sensitive sectors such as subsistence agriculture, higher population exposure to hazards.

Up to 2 marks for explaining adaptive capacity differences.

e.g., lack of financial resources, weaker governance, limited access to technology or infrastructure.

1 mark for a clear example that illustrates the contrast.

e.g., Bangladesh vulnerable to flooding but with limited resources, versus the Netherlands with advanced flood-defence systems.

Question 1 (2 marks)

Identify two societal sectors that are directly affected by climate change impacts.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for each correct sector identified, up to 2 marks.

Acceptable answers include:Health

Water resources

Agriculture/food security

Infrastructure/urban systems