IB Syllabus focus:

‘Waste volume/composition vary with socioeconomics, politics, environment and technology. Waste often travels from high-income to low-income countries, raising justice concerns.’

The generation and management of solid domestic waste (SDW) is shaped by economic development, politics, cultural behaviour, environmental conditions, and advancing technologies. Shifts in waste production highlight inequalities.

Changing Volumes of Waste

Socioeconomic Factors

Levels of income and consumption patterns are major drivers of waste volumes.

High-income countries generate more non-biodegradable waste, such as plastics, metals, and packaging.

Low-income countries produce higher proportions of organic waste, often due to agricultural reliance and limited access to packaged goods.

Urbanisation intensifies waste creation because densely populated areas concentrate consumption and production. Affluent societies often adopt single-use consumer lifestyles, whereas subsistence economies recycle and reuse out of necessity.

Urbanisation: The growth and expansion of cities and towns, typically involving shifts from rural agricultural lifestyles to urban industrial and service-based economies.

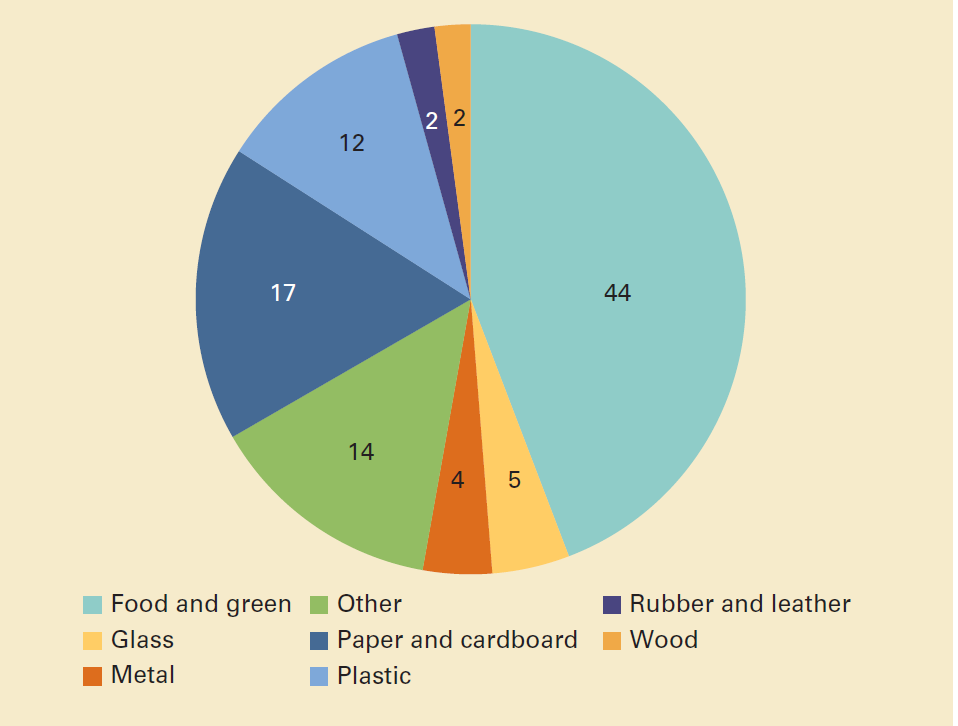

High-income countries generate relatively less food and green waste, at 32 percent of total waste, and generate more dry waste that could be recycled, including plastic, paper, cardboard, metal, and glass, which account for 51 percent of waste.

Stacked bar charts show global municipal solid waste composition and how the shares of organics versus “dry” recyclables vary across income levels. This visual reinforces that composition shifts with development, affecting appropriate management options and infrastructure. Source.

Political Factors

Government priorities, policy frameworks, and regulation strongly affect waste volumes.

Nations with strong environmental governance implement policies encouraging recycling, composting, and extended producer responsibility.

In politically unstable regions, waste collection systems are often weak or underfunded, leading to unmanaged dumping and rising volumes.

Legislation such as bans on single-use plastics demonstrates how policy can significantly reduce waste generation.

Environmental and Geographic Factors

Environmental conditions also influence waste characteristics.

Hot, humid climates accelerate biodegradation, affecting the type and volume of waste requiring disposal.

Geographic constraints, such as limited land area (e.g., island nations), reduce landfill capacity, forcing higher reliance on incineration or waste exportation.

Technological Factors

Advancements in waste processing technologies directly influence waste volumes and composition.

Waste-to-energy plants reduce landfill dependence but require costly infrastructure.

Circular economy innovations, such as product design for reuse and materials recovery, reduce overall volumes over time.

In developing nations, limited technological capacity results in higher unmanaged waste volumes.

Global Injustice in Waste Distribution

Waste Exports

A major injustice arises when high-income countries export large volumes of hazardous or non-recyclable waste to low-income nations. This is often justified under the guise of recycling but frequently results in environmental degradation.

Waste Colonialism: The practice of exporting waste, particularly hazardous or non-recyclable material, from wealthy countries to less developed nations, shifting environmental burdens unequally.

These imports can overwhelm local waste-management systems, leading to toxic dumping, water contamination, and exposure risks for vulnerable populations.

Economic Incentives and Power Imbalances

Low-income nations may accept imported waste due to short-term economic incentives, such as jobs or foreign exchange earnings.

This arrangement creates structural dependency and entrenches inequalities, as these countries lack the infrastructure to process or safely dispose of hazardous imports.

Environmental Justice Concerns

The injustice is rooted in unequal exposure to environmental risks. Communities in recipient countries face health hazards, contaminated soil, and polluted air and water.

Informal waste-picking communities often bear the greatest risks, with limited labour rights or protective measures.

Environmental degradation disproportionately affects marginalised groups who rely directly on land and water for survival.

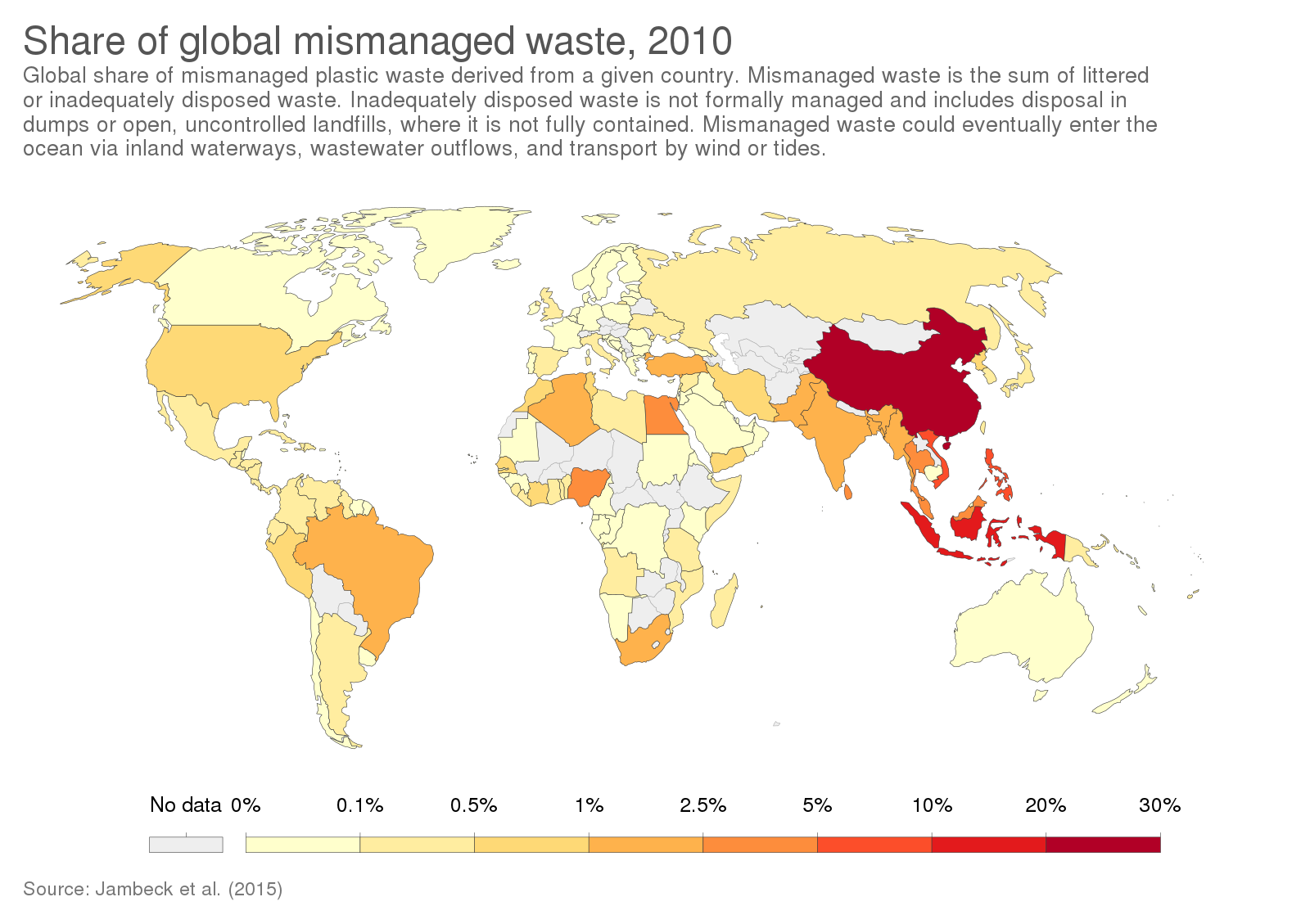

A world map highlights each country’s share of the global total of mismanaged plastic waste, indicating where pollution burdens are greatest. This aligns with environmental justice concerns in lower-income contexts where management capacity is limited. Source.

Informal waste-picking communities often bear the greatest risks, with limited labour rights or protective measures.

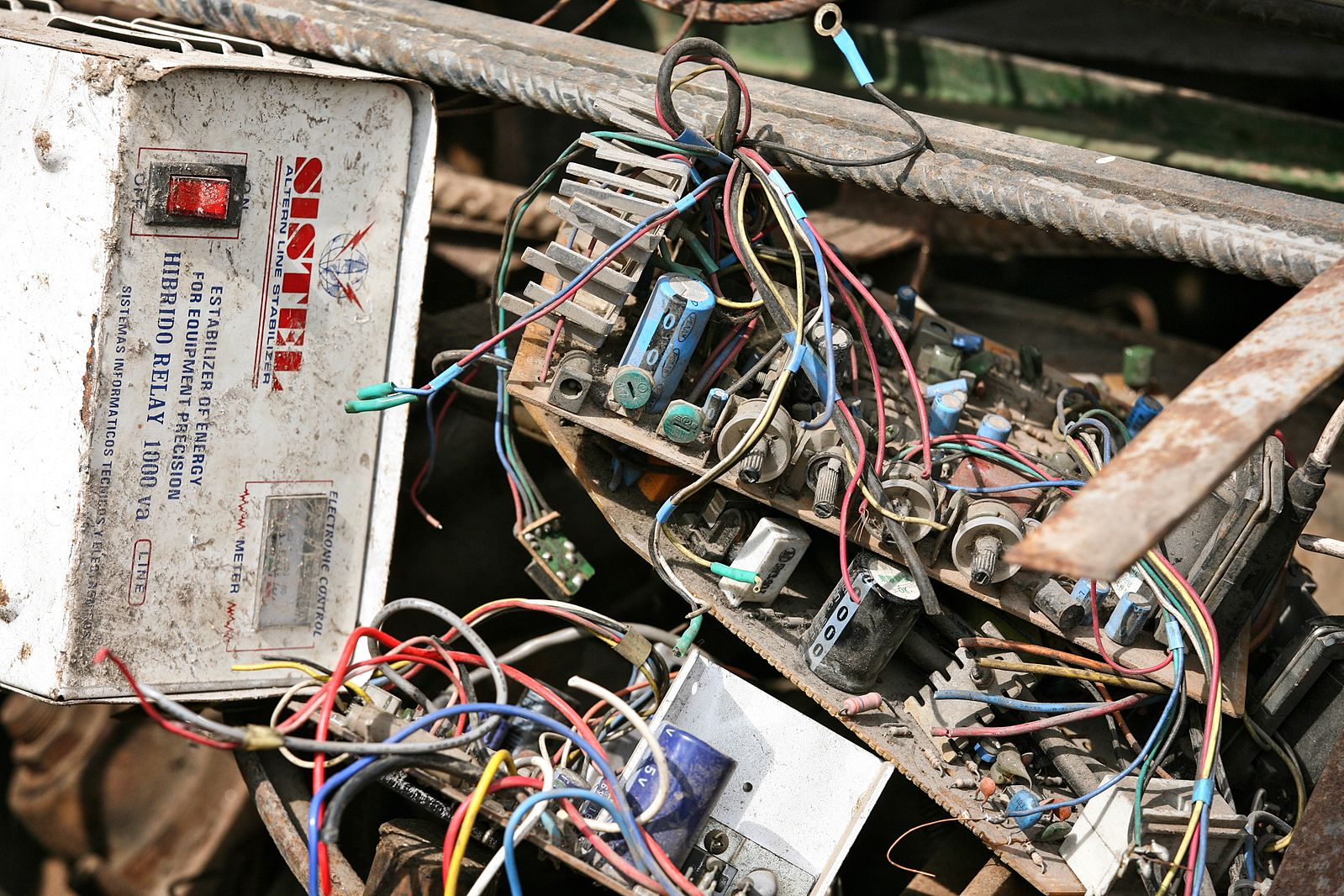

A high-resolution photograph shows manual dismantling of electronic waste in a basic facility, illustrating exposure risks typical of informal recycling. While not a diagram, the image concretises the justice issues discussed in the text. Source.

Case Example Dynamics (without names or specifics)

High-income nations export electronic waste, rich in metals but containing toxic substances.

Processing is often performed manually by informal workers in unsafe conditions, creating public health crises.

Interaction of Factors

Feedback Loops

Socioeconomic development and politics interact with waste injustice.

As consumption rises in middle-income economies, imported waste exacerbates domestic challenges.

Weak political oversight enables illegal dumping, which further degrades ecosystems and public health, reducing economic potential.

Technology and Justice Links

While new waste treatment technologies can improve equity, they are concentrated in wealthy nations. Without access, low-income countries remain dependent on imports of poorly recyclable waste.

Approaches to Address Waste Injustice

Strengthening International Regulation

Basel Convention: A global treaty controlling cross-border movement of hazardous waste, aiming to reduce dumping in low-income countries.

Stronger enforcement and closing loopholes are essential to reduce injustice.

National Policy Shifts

Implementing import bans on hazardous waste reduces exposure.

Investing in domestic waste infrastructure (recycling centres, composting facilities) lessens vulnerability to exploitation.

Technological Cooperation

Sharing waste reduction technologies and building local capacity reduces reliance on harmful imports.

Encouraging closed-loop recycling systems within national borders can protect communities and ecosystems.

Key Points to Remember

Waste volumes and composition are shaped by socioeconomic, political, environmental, and technological factors.

High-income nations generate more synthetic and non-biodegradable waste, while low-income nations generate more organic waste.

Waste colonialism occurs when high-income nations export waste to low-income nations, creating significant environmental justice issues.

Addressing injustice requires international regulation, stronger national policies, and fair access to waste management technologies.

FAQ

Globalisation increases consumption of imported goods, leading to greater packaging and electronic waste. As economies integrate, waste often flows across borders, sometimes legally as recyclable materials, but also illegally as hazardous waste shipments.

This reinforces injustice when high-income nations offload waste to low-income countries lacking proper infrastructure, creating uneven environmental burdens.

Cultural practices affect both the type and amount of waste produced.

Societies with strong traditions of reuse or repair generate less disposable waste.

Cultural norms around food preparation can increase organic waste.

Attitudes towards recycling and environmental responsibility shape the success of waste management systems.

Informal workers recover materials that would otherwise be lost, contributing to recycling and resource efficiency.

However, they often work without protective equipment, face exposure to toxins, and receive low financial returns. This illustrates how vulnerable groups carry disproportionate health risks while wealthier populations benefit from waste disposal.

Uncontrolled dumping and mismanaged imports can lead to:

Persistent soil and water contamination

Loss of biodiversity from habitat degradation

Accumulation of microplastics in ecosystems

Increased greenhouse gas emissions from uncontrolled decomposition

These impacts extend beyond national borders, affecting global ecological health.

The Basel Convention regulates transboundary movement of hazardous waste, requiring consent from importing countries.

Amendments now restrict exports from high-income to low-income countries, aiming to curb waste colonialism.

Challenges remain, including weak enforcement, loopholes that mislabel hazardous shipments as recyclable, and economic pressures that incentivise acceptance of waste.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Define the term waste colonialism and explain how it creates an environmental justice issue.

Mark Scheme:

1 mark for correctly defining waste colonialism: the export of hazardous or non-recyclable waste from high-income to low-income countries, shifting environmental burdens.

1 mark for explaining the justice issue: recipient countries face health risks, soil/water contamination, or unequal exposure to pollution.

Question 2 (5 marks)

Discuss how socioeconomic and political factors influence the volumes and composition of solid domestic waste in different countries.

Mark Scheme:

1 mark for recognising that high-income countries generate more non-biodegradable or recyclable materials (plastic, metals, packaging).

1 mark for recognising that low-income countries generate larger proportions of organic waste (food, agricultural).

1 mark for noting how rising affluence and urbanisation increase overall waste volumes.

1 mark for describing the role of strong governance or legislation in reducing or shaping waste (e.g., bans on single-use plastics, recycling policies).

1 mark for linking weak governance/political instability to higher unmanaged waste or illegal dumping.