IB Syllabus focus:

‘Use taxes, incentives, legislation, education, campaigns and better facilities to shift behaviours and improve outcomes.’

Promoting sustainable solid domestic waste (SDW) management requires societies to combine economic, legal, educational, and infrastructural approaches. Effective strategies reduce waste, encourage reuse, and protect environmental and social well-being.

Understanding Sustainable SDW Management

Sustainable SDW management involves approaches that balance environmental protection, economic feasibility, and social equity. The goal is to minimise waste generation, ensure efficient use of resources, and reduce environmental harm.

Sustainable SDW management: The coordinated use of strategies such as prevention, recycling, and controlled disposal to minimise waste’s ecological and societal impacts.

Unlike short-term fixes, sustainable management focuses on long-term resilience by influencing behaviour and improving systems.

Economic Instruments: Taxes and Incentives

Economic tools shift individual and corporate behaviour by altering the financial costs or benefits of waste-related actions.

Taxes

Governments impose waste disposal taxes or landfill levies to discourage unsustainable disposal. By making environmentally harmful practices more expensive, taxes promote waste reduction.

Landfill tax: Charges per tonne of waste sent to landfill.

Plastic bag levy: Direct fee on single-use plastics to cut consumption.

Incentives

Incentives reward sustainable behaviour, encouraging people and companies to manage waste responsibly. Examples include:

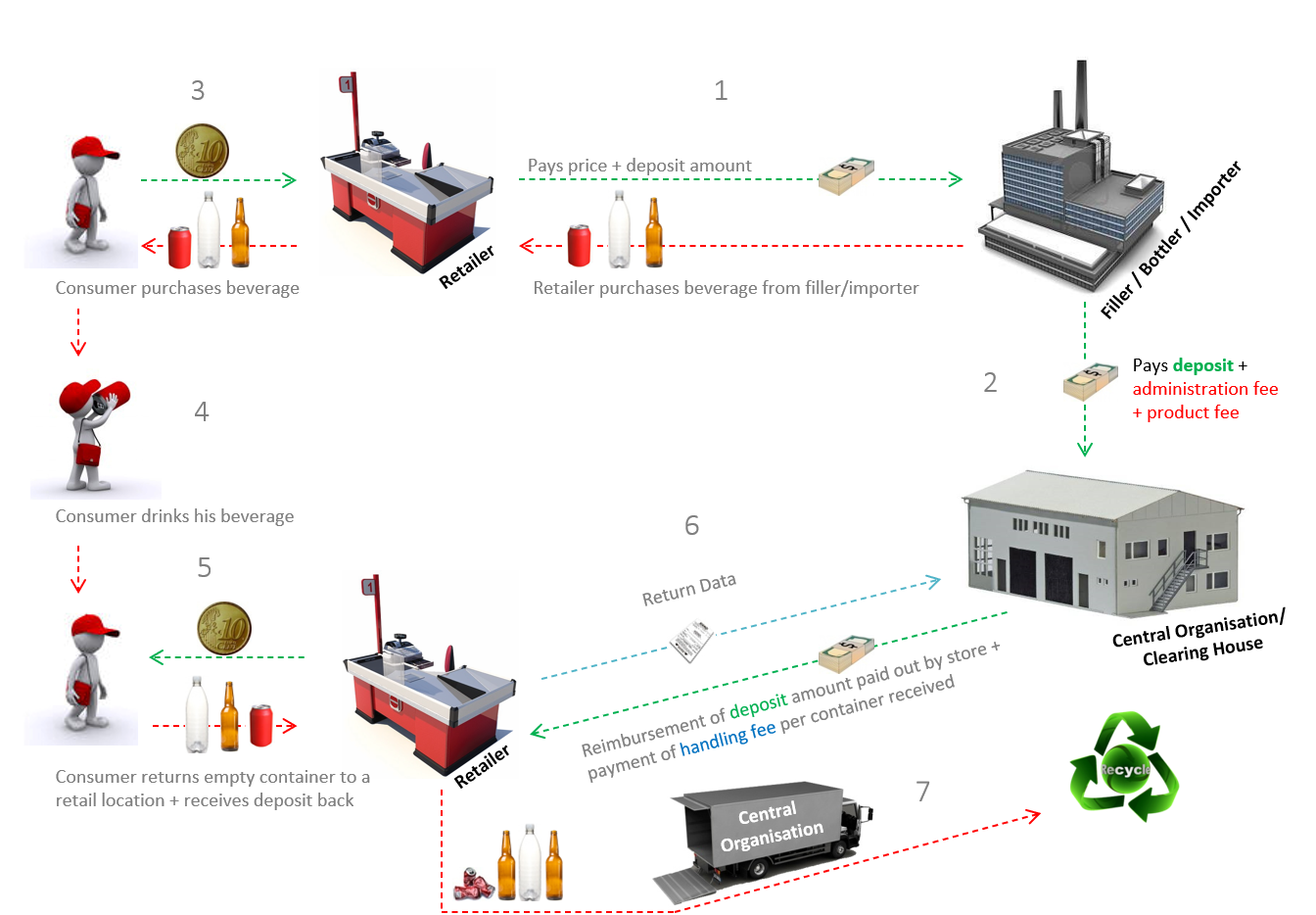

Deposit-refund schemes: Consumers pay a small deposit on items such as bottles, refunded when the item is returned for recycling.

This schematic shows the deposit-return flow for beverage containers, from point of purchase to refund and material recovery, highlighting the consumer incentive and producer responsibility linkages. The diagram reinforces how economic instruments reduce waste leakage by rewarding correct returns. It includes only core steps relevant to the syllabus treatment of incentives. Source.

Subsidies for recycling plants: Governments reduce costs for facilities that increase recycling rates.

Deposit-refund scheme: A system where consumers pay an upfront deposit on a product that is refunded upon its return for reuse or recycling.

Taxes and incentives together create a push–pull system that discourages waste while rewarding sustainability.

Legislative Measures

Legislation is central to ensuring compliance and long-term changes in waste management. Laws establish responsibilities, restrictions, and penalties.

Key examples:

Bans on hazardous materials such as asbestos or toxic chemicals.

Mandatory recycling laws requiring households or businesses to separate waste.

Extended producer responsibility (EPR): Companies must manage their products’ waste throughout the life cycle.

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR): A policy approach where producers are accountable for the collection, recycling, or disposal of their products after consumer use.

Legislation ensures uniform standards across society, reducing the risk of unsustainable practices driven by short-term profits.

Education and Awareness Campaigns

Changing behaviour requires informing and engaging the public. Education highlights the environmental consequences of poor SDW management and empowers individuals to act.

Formal Education

Integration of waste management into school curricula.

Student-led projects, such as composting or recycling initiatives, build lifelong habits.

Public Campaigns

Governments and NGOs run campaigns to raise awareness and normalise sustainable behaviour. Examples include:

Mass media campaigns discouraging single-use plastics.

Community clean-up events that foster responsibility.

By making sustainability a social norm, campaigns strengthen the impact of economic and legislative measures.

Infrastructure and Facilities

Even with education and laws, sustainable SDW management fails without accessible infrastructure. Facilities enable behavioural change by making sustainable choices easy and practical.

Examples of necessary infrastructure include:

Recycling collection points located near residential areas.

A clearly labelled plastic-bottle recycling bin exemplifies the facility provision needed to support household participation in source separation. Such infrastructure operationalises policy by making correct disposal convenient and visible. The image is limited to container recycling and does not add extraneous details beyond the syllabus scope. Source.

Composting facilities for organic household waste.

Hazardous waste collection centres to prevent improper disposal.

Waste-to-energy plants that convert non-recyclable waste into usable energy.

Improved infrastructure supports circular systems where materials remain in use longer.

Integration of Strategies

No single approach is sufficient. Effective waste management combines taxes, incentives, legislation, education, campaigns, and infrastructure into a coordinated strategy. For example:

A plastic bag levy (tax) is reinforced by public awareness campaigns and supported by alternatives at supermarkets (infrastructure).

Deposit-refund schemes (incentive) succeed when collection centres are accessible and when legislation mandates producer participation.

Such integration addresses environmental, social, and economic dimensions simultaneously.

Barriers and Challenges

Despite clear benefits, promoting sustainable SDW management faces obstacles:

Economic resistance: Businesses may oppose taxes or EPR due to increased costs.

Public reluctance: Habits take time to change, and convenience often outweighs sustainability.

Infrastructure gaps: Low-income countries may lack facilities to support sustainable waste systems.

Political will: Weak enforcement undermines effectiveness of laws and policies.

Addressing these barriers requires international cooperation, investment, and persistent public engagement.

Case Study Features (for context, not examples)

When assessing strategies, students should recognise:

The importance of multi-level governance (local, national, international).

The role of technological innovation, such as smart bins or tracking systems.

The link between waste management and justice issues, as waste burdens often fall on marginalised communities.

FAQ

Cultural values strongly shape how communities perceive waste and sustainability. In societies where reuse and repair are traditional, campaigns promoting recycling or composting often succeed quickly.

In contrast, consumer-driven cultures may require stronger economic incentives or strict legislation to shift behaviours. Cultural alignment ensures that strategies are not only introduced but also accepted and normalised.

Technology strengthens enforcement and awareness by:

Smart bins that record usage and track contamination.

Apps that guide households on correct disposal and collection schedules.

Monitoring systems that help authorities enforce recycling laws.

By reducing errors and increasing convenience, technology supports compliance with legislation and enhances the reach of educational campaigns.

Deposit-refund schemes provide a direct financial incentive, creating a clear link between consumer behaviour and reward. Unlike general recycling policies, they reduce litter by guaranteeing value recovery.

They also transfer part of the responsibility to producers and retailers, ensuring infrastructure is in place for efficient returns. This shared responsibility makes them more reliable than voluntary recycling systems.

Campaigns go beyond immediate compliance by embedding sustainable practices into daily routines. Over time, repeated messaging creates social norms, where improper disposal becomes socially unacceptable.

By targeting schools, communities, and workplaces, campaigns ensure that younger generations adopt sustainable behaviours that persist into adulthood, strengthening long-term waste management outcomes.

Infrastructure such as recycling plants or collection centres requires significant investment, which many low-income regions cannot afford. Political instability or weak governance may also limit maintenance and enforcement.

Geographic challenges, such as remote or informal settlements, further hinder access. Without external funding or partnerships, strategies relying heavily on infrastructure may remain unrealistic, even if education and campaigns succeed.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Outline two methods governments can use to promote sustainable solid domestic waste (SDW) management.

Mark scheme:

Identification of a valid method (1 mark each, up to 2 marks).

Acceptable answers include:Taxes (e.g., landfill levies, plastic bag charges) (1 mark).

Incentives (e.g., deposit-refund schemes, subsidies for recycling facilities) (1 mark).

Legislation (e.g., mandatory recycling laws, bans on hazardous materials) (1 mark).

Education and awareness campaigns (1 mark).

Provision of infrastructure (e.g., recycling collection points, composting facilities) (1 mark).

Note: Award a maximum of 2 marks. No credit for vague or incorrect answers.

Question 2 (5 marks)

Discuss how a combination of strategies can improve the effectiveness of sustainable SDW management. Use examples in your answer.

Mark scheme:

Explanation of at least two different strategies (1 mark each, up to 2 marks).

Linking strategies together to show integration (1 mark).

Reference to specific examples (e.g., plastic bag levy with supporting campaigns, deposit-refund scheme with accessible collection points, EPR with legislation) (1 mark).

Analysis of why integration is more effective than isolated measures (e.g., economic incentives supported by education reduce resistance and improve compliance) (1 mark).

Maximum: 5 marks.

Partial credit awarded for incomplete but valid points.