OCR Specification focus:

‘Apply relevant specification content and scientific understanding to justify design decisions in the given practical context.’

Introduction

Applying prior chemical knowledge allows chemists to design effective and scientifically valid experiments by integrating theoretical understanding with practical skills, ensuring accuracy, safety, and logical experimental outcomes.

Applying Prior Chemical Knowledge

When designing an experiment in A-Level Chemistry, students must demonstrate the ability to use their existing chemical knowledge to support each decision made about the method, apparatus, and expected outcomes. This process requires linking theory to practice — understanding why a particular method is suitable and how it aligns with established chemical principles.

The Role of Prior Knowledge

Prior knowledge in chemistry encompasses the fundamental principles from across the specification, including atomic structure, bonding, energetics, rates of reaction, and equilibrium. This theoretical foundation allows for informed decision-making in practical planning, ensuring that experiments are scientifically sound and yield meaningful results.

For example, when designing a titration, knowledge of acid–base reactions, stoichiometry, and indicator selection is required to ensure the chosen method produces valid and accurate data.

Integrating Chemical Theory with Experiment Design

Effective experimental design involves translating abstract chemical theory into measurable, controlled procedures. The student should:

Use theoretical understanding to predict reaction outcomes.

Apply chemical equations and mole relationships to determine reactant quantities.

Anticipate potential sources of error based on known reaction conditions or apparatus limitations.

Select reagents and conditions that ensure reactions proceed safely and efficiently.

This integration of knowledge and planning helps to achieve reliable and reproducible results.

Understanding Chemical Reactions in Practical Contexts

Every experimental decision — such as choosing a reagent, solvent, or temperature — should be supported by the underlying chemistry.

Reaction Conditions

Students must consider:

Temperature: affects reaction rate and equilibrium position.

Concentration: influences rate and yield according to collision theory.

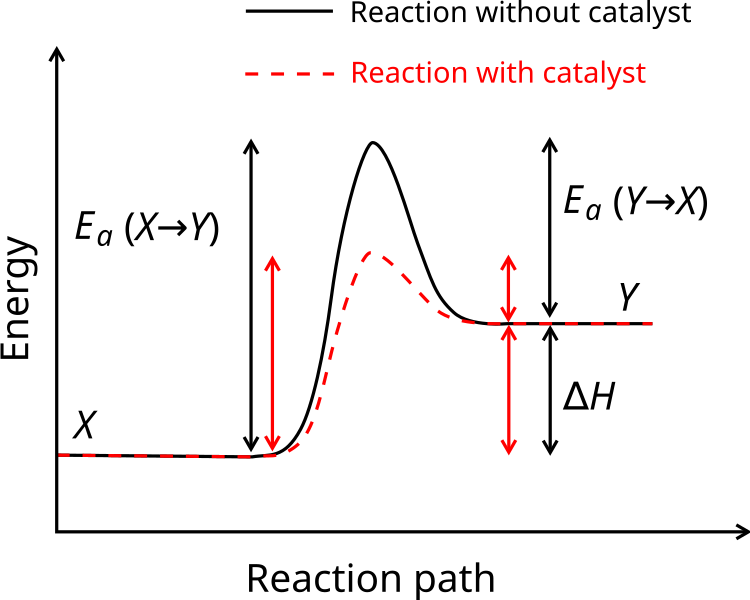

Catalysts: lower activation energy to increase rate without being consumed.

Activation Energy: The minimum energy required for a reaction to occur upon collision between reactant particles.

Physical and Chemical Properties

Knowledge of chemical and physical properties (such as solubility, volatility, and stability) is critical in predicting outcomes and avoiding hazards.

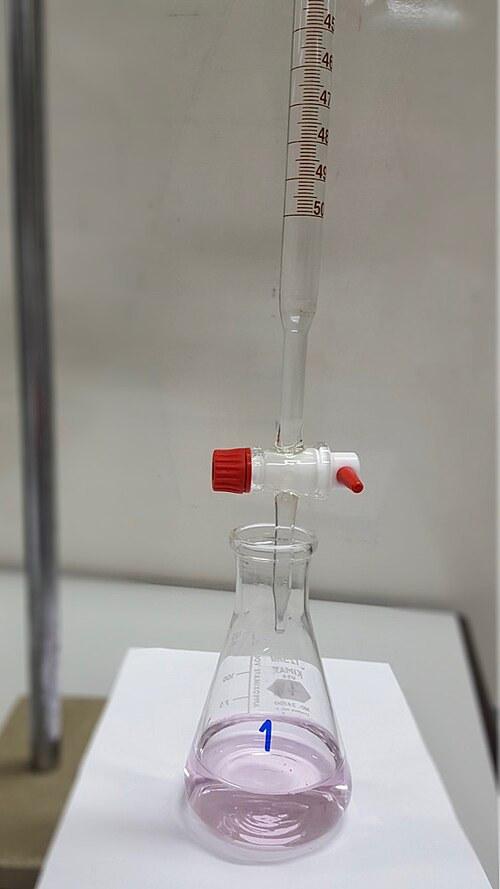

Apparatus used in a typical acid–base titration: the burette delivers a standard solution, the conical flask contains the analyte plus indicator, enabling volume measurement for quantitative analysis. (Extra detail: includes indicator colour change and volumetric pipette not explicitly required by the syllabus but still helpful context.) Source

For instance, using ethanol as a solvent for non-polar organic compounds draws upon an understanding of solvent polarity and intermolecular forces.

Selecting Appropriate Reagents and Apparatus

When designing an experiment, prior knowledge ensures that each reagent and piece of apparatus serves a clear chemical purpose. The following factors are important:

Purity of reagents: impure substances may introduce side reactions.

Reactivity of reagents: unnecessary hazards or unwanted products can arise from inappropriate choices.

Material compatibility: corrosive chemicals should not be used with unsuitable apparatus materials (e.g. concentrated acids and metal).

Students must justify these selections with reasoning grounded in their knowledge of chemical reactivity, oxidation–reduction, or acid–base chemistry.

Predicting Expected Results and Observations

Prior chemical knowledge allows students to anticipate observable changes such as colour changes, gas evolution, or precipitate formation. These expectations guide the setup and interpretation of results.

For example:

A reaction between Cu²⁺ ions and hydroxide ions should produce a blue precipitate of copper(II) hydroxide.

Heating hydrated copper(II) sulfate should yield a colour change from blue to white as water is driven off.

Being able to justify these outcomes demonstrates an understanding of ionic equations, hydration, and thermal decomposition.

Quantitative Relationships in Experiment Design

Chemical knowledge extends to quantitative analysis — particularly when calculating quantities or analysing results.

Ideal Gas Equation (pV = nRT)

p = Pressure (Pa)

V = Volume (m³)

n = Number of moles (mol)

R = Gas constant (8.31 J mol⁻¹ K⁻¹)

T = Temperature (K)

Students use such relationships to determine the amounts of substances required, predict gas volumes, or calculate expected yields. These calculations rely on prior learning of mole theory and stoichiometric relationships.

Reaction‑coordinate energy diagram showing the energy barrier (activation energy) that must be overcome for a reaction to proceed; a lower barrier indicates a faster reaction (for example with a catalyst). (Extra detail: the diagram also shows a catalyst‑pathway, which is beyond this subsub‑topic’s core focus but still supports the understanding of design decisions.) Source

Safety and Risk Considerations

Scientific understanding also informs safe working practice. Recognising the hazards associated with chemicals or reactions depends on prior knowledge of their toxicological and reactivity properties.

Students should consider:

Flammability of solvents such as ethanol and propanone.

Corrosive nature of concentrated acids and alkalis.

Toxic fumes from halogenated compounds or nitrogen oxides.

By applying this knowledge, appropriate safety precautions — such as using a fume cupboard, wearing protective eyewear, or substituting safer reagents — can be implemented.

Evaluating the Suitability of a Design

Once an experimental design is proposed, prior chemical knowledge helps evaluate whether it will meet the intended aims. Students should critically assess:

Whether the chosen conditions (e.g. temperature, concentration) are chemically appropriate.

Whether the expected reaction pathway aligns with established mechanisms.

Whether the data collected will provide sufficient evidence to test the hypothesis.

This stage demonstrates the student’s ability to connect conceptual chemistry to experimental evidence, ensuring logical reasoning and sound methodology.

Applying Knowledge from Across the Specification

To fully justify design choices, students must integrate ideas from multiple specification areas, including:

Physical Chemistry: applying equilibrium and kinetic concepts to reaction feasibility.

Inorganic Chemistry: understanding oxidation states and ionic equations to predict reaction outcomes.

Organic Chemistry: applying mechanisms and functional group chemistry to determine suitable reagents and conditions.

This cross-topic application illustrates how practical design is rooted in a holistic understanding of chemistry, mirroring the expectations of real scientific research and industrial laboratory work.

Linking Theory, Observation, and Evaluation

Ultimately, applying prior chemical knowledge ensures that practical chemistry is not performed blindly but is guided by informed, evidence-based reasoning. Students must use their understanding to justify every decision, from reagent choice to observation recording, thereby producing experiments that are not only practical but scientifically valid and conceptually rigorous.

FAQ

Applying prior chemical knowledge means using theoretical understanding from previous study areas to make informed experimental decisions. Students must draw upon knowledge of bonding, kinetics, equilibrium, and energetics to justify choices about reagents, conditions, and apparatus. This approach ensures results are valid, reproducible, and scientifically sound.

Reaction mechanisms explain how reactants convert into products, step by step. Understanding these helps predict by-products, identify conditions favouring specific outcomes, and prevent incomplete reactions. For example, knowing whether a reaction proceeds via nucleophilic substitution or elimination determines the correct solvent and temperature to use.

Prior chemical understanding enables accurate selection of:

Temperature: ensuring reactions proceed efficiently without decomposition.

Concentration: maintaining measurable but safe reaction rates.

Catalyst use: reducing activation energy for faster reactions.

These considerations prevent wasted reagents and ensure reliable data collection.

Students who understand the properties and hazards of chemicals can predict risks before experimentation.

Acids and bases: require neutralisation or dilution protocols.

Volatile or toxic substances: may demand fume cupboard use.

This foresight supports safer, compliant laboratory procedures and demonstrates good scientific practice.

Apparatus choice affects precision, safety, and the validity of data. For instance:

Burettes and pipettes are selected for accurate volume measurements.

Conical flasks reduce splashing during titrations.

Justifying each selection with chemical reasoning shows understanding of experimental aims and enhances data reliability.

Practice Questions

A student is designing an experiment to investigate how the concentration of hydrochloric acid affects the rate of reaction with magnesium ribbon. Explain one reason why the student should use equal lengths of magnesium ribbon in each trial. (2 marks)

1 mark for identifying the control of a variable: Using equal lengths ensures the same surface area of magnesium is used in each experiment.

1 mark for justification: This allows a fair comparison of reaction rates since only acid concentration changes.

A student plans an experiment to determine the enthalpy change of neutralisation between hydrochloric acid and sodium hydroxide. Using your prior chemical knowledge, explain how the student should design this experiment to ensure accurate and valid results. Include reference to apparatus, measurements, and potential sources of error. (5 marks)

1 mark: Identifies suitable apparatus such as a polystyrene cup and lid to minimise heat loss.

1 mark: Describes accurate measurement of acid and alkali volumes using a pipette and burette.

1 mark: States temperature should be measured before and after mixing to find temperature change (∆T).

1 mark: Explains that mixing should be thorough to ensure uniform temperature distribution.

1 mark: Recognises potential heat loss to surroundings or incomplete reaction as sources of error and suggests minimising these for accuracy.