OCR Specification focus:

‘Construct Born–Haber cycles using formation, ionisation, atomisation and electron affinity; perform related calculations.’

Born–Haber cycles are energy cycles that link measurable enthalpy changes to lattice enthalpy, allowing ionic bond strength to be determined using Hess’s law.

Purpose of Born–Haber Cycles

Born–Haber cycles are used to calculate lattice enthalpy, which cannot be measured directly. They rely on Hess’s law, stating that the total enthalpy change for a reaction is independent of the pathway taken.

The cycle breaks the formation of an ionic solid from its elements into a sequence of theoretical steps involving gaseous atoms and ions. By combining known enthalpy changes, the unknown lattice enthalpy can be calculated.

Born–Haber cycles are most commonly applied to ionic compounds such as sodium chloride or magnesium oxide, where bonding is dominated by electrostatic attraction between oppositely charged ions.

Standard Enthalpy of Formation

The cycle is built around the standard enthalpy of formation, which provides the overall enthalpy change for forming one mole of an ionic solid from its elements in their standard states.

Standard enthalpy of formation: The enthalpy change when one mole of a compound is formed from its elements in their standard states under standard conditions.

This value is usually obtained experimentally and is placed as the overall enthalpy change in the Born–Haber cycle.

Atomisation Enthalpy

To form gaseous ions, elements must first be converted into gaseous atoms. This step is described by enthalpy change of atomisation.

Enthalpy change of atomisation: The enthalpy change when one mole of gaseous atoms is formed from an element in its standard state.

For metals, this involves converting solid metal atoms into gaseous atoms. For non-metals such as chlorine, atomisation involves breaking covalent bonds, so half the bond enthalpy of Cl₂ is used.

This step is always endothermic, as energy is required to separate atoms.

Ionisation Energy

Once gaseous metal atoms are formed, electrons must be removed to form positive ions. This is represented by ionisation energies.

Ionisation energy: The enthalpy change when one mole of electrons is removed from one mole of gaseous atoms or ions.

Key points about ionisation energy in Born–Haber cycles:

Always endothermic

Multiple ionisation energies are required for ions with charges greater than +1

Successive ionisation energies increase due to increased nuclear attraction

For example, magnesium requires both first and second ionisation energies to form Mg²⁺(g).

Electron Affinity

Non-metal atoms gain electrons to form negative ions. This step is described by electron affinity.

Electron affinity: The enthalpy change when one mole of electrons is added to one mole of gaseous atoms to form one mole of gaseous negative ions.

Important features of electron affinity:

Often exothermic, due to attraction between the nucleus and incoming electron

Second electron affinity is always endothermic because an electron is added to a negatively charged ion

For ions such as O²⁻, both first and second electron affinities must be included

Electron affinity values significantly influence lattice enthalpy calculations for compounds containing highly charged anions.

Lattice Enthalpy

The final step in the cycle is the formation of the ionic lattice from gaseous ions.

Lattice enthalpy: The enthalpy change when one mole of an ionic solid is formed from its gaseous ions.

In Born–Haber cycles, lattice enthalpy is usually exothermic, reflecting the strong electrostatic attractions between oppositely charged ions.

OCR defines lattice enthalpy specifically in terms of formation from gaseous ions, so the sign and definition must be consistent when performing calculations.

Constructing a Born–Haber Cycle

A Born–Haber cycle links all the enthalpy changes using Hess’s law. It can be represented as an energy level diagram or as a written enthalpy cycle.

The cycle breaks the formation of an ionic solid into atomisation, ionisation, electron affinity and lattice enthalpy steps.

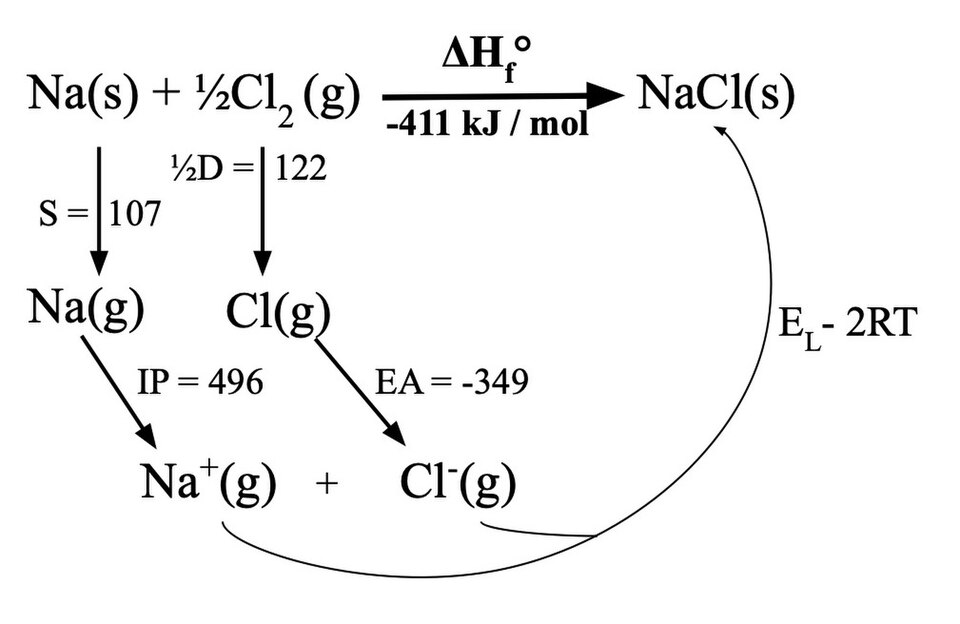

This diagram shows the Born–Haber cycle for sodium chloride, breaking the formation of NaCl(s) into atomisation, ionisation, electron affinity and lattice enthalpy steps that sum to the enthalpy of formation. Source

Key steps included in every cycle:

Formation of gaseous atoms from elements (atomisation)

Formation of gaseous ions (ionisation energies and electron affinities)

Formation of the ionic lattice (lattice enthalpy)

Overall formation of the ionic solid (enthalpy of formation)

Each step must be chemically accurate and correctly signed as endothermic or exothermic.

Calculations Using Born–Haber Cycles

Calculations involve rearranging Hess’s law to determine an unknown enthalpy change, most commonly lattice enthalpy.

Hess’s law (enthalpy cycle)

ΔH_f = Σ(endothermic steps) + Σ(exothermic steps)

ΔH_f = standard enthalpy of formation (kJ mol⁻¹)

The exact algebraic form depends on how the cycle is arranged, but careful attention must be paid to:

Correct stoichiometry, especially for diatomic molecules

Inclusion of all required ionisation energies and electron affinities

Correct signs for each enthalpy change

When you build the cycle, keep sign conventions consistent: ionisation and atomisation steps are endothermic, while electron affinity and lattice formation are typically exothermic.

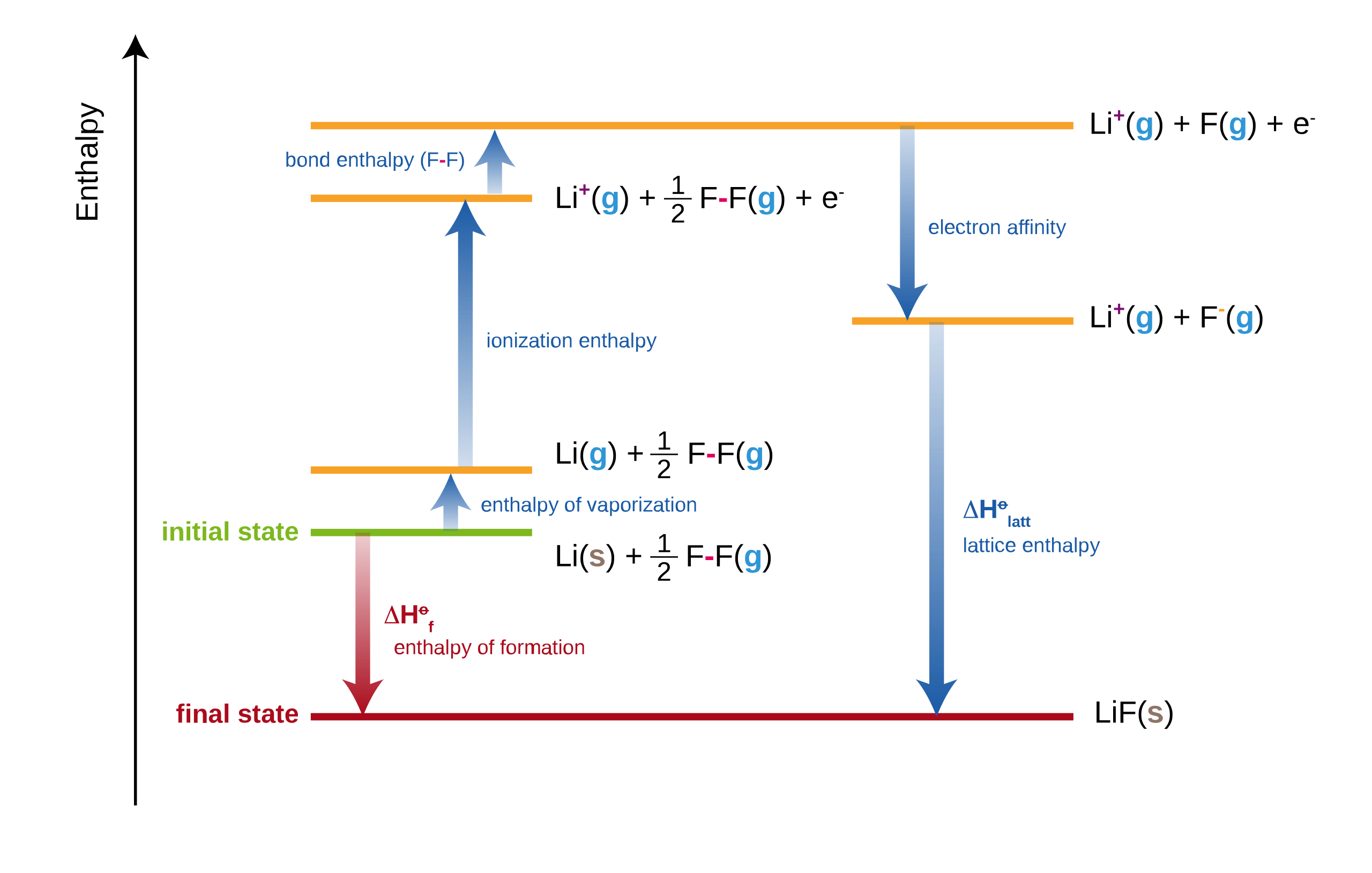

This diagram illustrates a Born–Haber cycle for lithium fluoride, emphasising the direction and sign conventions of each enthalpy change. It highlights how electron affinity and lattice enthalpy are incorporated when applying Hess’s law. Source

A clear, logical approach to constructing the cycle is essential before attempting any calculation, as errors usually arise from missing or mis-signed steps.

Importance and Applications

Born–Haber cycles allow chemists to:

Compare ionic bond strengths through lattice enthalpy values

Explain trends in stability of ionic compounds

Evaluate the energetic feasibility of forming ionic solids

They are a central application of thermodynamics in inorganic chemistry and are frequently assessed in OCR A-Level Chemistry through structured and unstructured questions requiring careful reasoning rather than rote learning.

FAQ

Born–Haber cycles are based on enthalpy changes that relate directly to the formation of an ionic lattice. Using gaseous ions avoids introducing additional enthalpy changes, such as hydration enthalpy, which are not part of lattice formation.

Gaseous ions provide a clear reference state, allowing lattice enthalpy to be defined consistently and compared between different ionic compounds.

OCR defines lattice enthalpy as the enthalpy change when one mole of an ionic solid forms from gaseous ions, which is exothermic.

Some data sources define lattice enthalpy as lattice dissociation, which is endothermic. Students must always check the definition used and apply the correct sign when constructing or rearranging a Born–Haber cycle.

Fractional atomisation enthalpies are used when elements exist as molecules rather than individual atoms.

For example:

Chlorine exists as Cl₂, so half the bond enthalpy is used to form one mole of Cl(g).

Oxygen exists as O₂, so half the O=O bond enthalpy is required per mole of atoms.

This ensures correct stoichiometry in the cycle.

Frequent errors include:

Forgetting second ionisation energies for 2+ metal ions

Omitting second electron affinity for 2− non-metal ions

Using incorrect signs for enthalpy changes

Failing to account for diatomic elements in atomisation steps

Careful checking of charges, states and stoichiometry reduces these mistakes.

Born–Haber cycles are designed to analyse ionic bonding by separating compounds into gaseous ions.

Covalent compounds do not form lattices of ions, so lattice enthalpy is not meaningful. As a result, alternative thermodynamic approaches are used for covalent systems, making Born–Haber cycles unsuitable for this type of bonding.

Practice Questions

Explain why lattice enthalpy cannot be measured directly and state how a Born–Haber cycle is used to determine it.

(2 marks)

1 mark for stating that lattice enthalpy cannot be measured directly because the formation of an ionic lattice from gaseous ions cannot be carried out experimentally.

1 mark for stating that a Born–Haber cycle uses Hess’s law and other measurable enthalpy changes (such as atomisation, ionisation energy and electron affinity) to calculate lattice enthalpy.

A student uses a Born–Haber cycle to calculate the lattice enthalpy of magnesium oxide, MgO.

(a) Identify and describe the enthalpy changes that must be included in a Born–Haber cycle for the formation of MgO from its elements.

(b) Explain why two ionisation energies of magnesium and two electron affinity terms for oxygen must be included.

(5 marks)

(a)

1 mark for identifying enthalpy change of formation of MgO from its elements.

1 mark for describing atomisation enthalpy for magnesium and oxygen to form gaseous atoms.

1 mark for describing ionisation energy to form Mg²⁺(g) from Mg(g).

(b)

1 mark for stating that magnesium forms a Mg²⁺ ion, so both first and second ionisation energies are required.

1 mark for stating that oxygen forms an O²⁻ ion, so two electron affinity steps are needed (first electron affinity and second electron affinity, with the second being endothermic).