OCR Specification focus:

‘Calculate ΔS for reactions from reactant and product entropies; handle related quantities.’

This section explores how entropy changes during chemical reactions and how numerical entropy values allow us to assess energetic dispersal across different chemical systems.

Calculating Entropy Change for Reactions

Entropy, ΔS, reflects the degree of energy dispersal in a system and helps chemists understand how particle arrangement influences reaction behaviour. Reaction entropy changes quantify the difference in disorder between products and reactants using standard entropy data.

When studying entropy, it is essential to distinguish between standard molar entropy, system entropy change, and total entropy change, all of which serve different thermodynamic purposes.

Entropy (S): A thermodynamic measure of the dispersal of energy or disorder within a chemical system, expressed in J K⁻¹ mol⁻¹.

Entropy values are always positive for substances, even at 0 K, because they incorporate contributions from molecular motions that remain above absolute zero.

Standard Molar Entropy and Its Application

Standard molar entropy values apply under standard conditions and provide a consistent reference for calculating reaction entropy. These values depend strongly on physical state and molecular complexity.

Standard Molar Entropy (S°): The entropy of one mole of a substance measured under standard conditions (298 K, 1 atm).

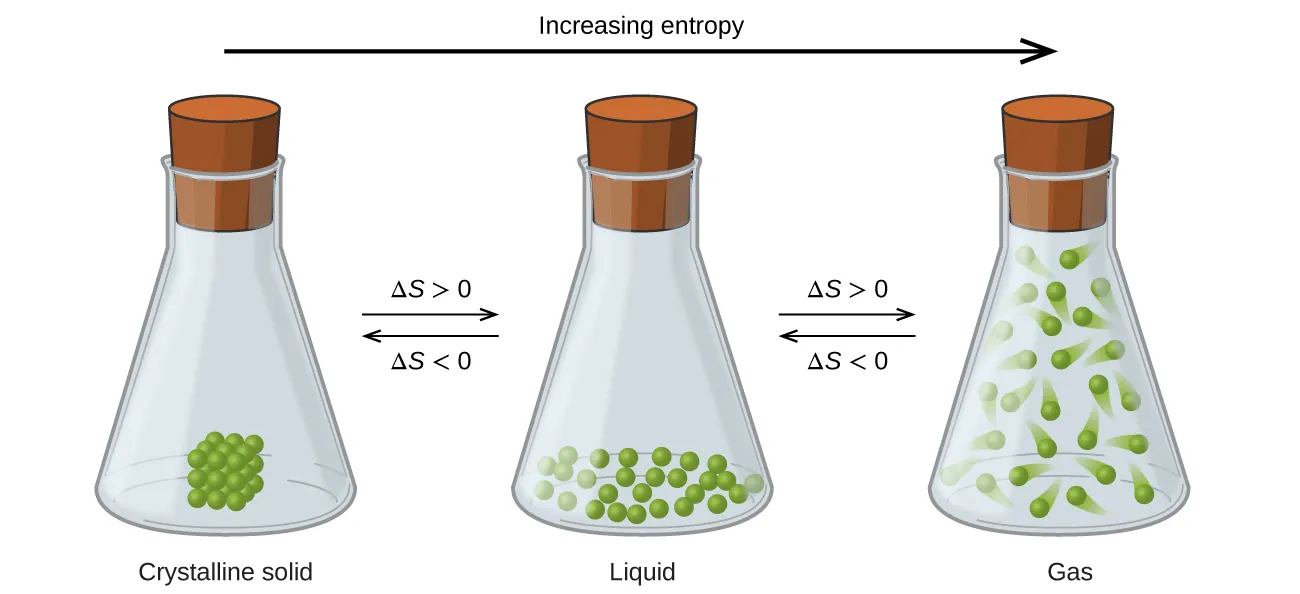

Because gases possess far greater molecular freedom than solids and liquids, gaseous species typically have the highest S° values. Reaction entropy calculations therefore often hinge on changes in the number of gaseous particles.

Entropy values appear in thermodynamic tables, and calculations use stoichiometric coefficients to weight each species’ contribution.

Using Entropy Values to Determine Reaction Entropy

The entropy change of a reaction, ΔS, arises from the difference between the sum of the entropies of products and the sum of the entropies of reactants.

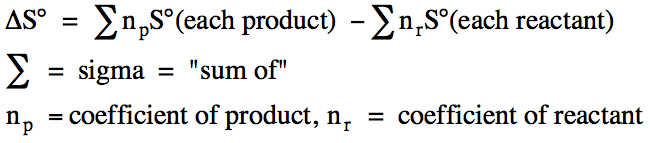

Reaction Entropy Change (ΔS) = ΣS°(products) − ΣS°(reactants)

ΔS: Entropy change of reaction, J K⁻¹ mol⁻¹

S°: Standard molar entropy of a species, J K⁻¹ mol⁻¹

Σ: Sum over all species, adjusted using stoichiometric coefficients

Chemical equations must be balanced before any ΔS calculation. Stoichiometric coefficients directly scale entropy contributions; for example, doubling a gaseous product doubles its entropy term.

The standard entropy change of reaction is calculated by summing standard molar entropies of the products and subtracting the summed standard molar entropies of the reactants, using stoichiometric coefficients.

This diagram shows the standard expression for ΔS° of a reaction, illustrating how stoichiometric coefficients scale each species’ entropy term. Source

Entropy changes become particularly insightful when assessing physical-state changes. Reactions producing additional gas molecules almost always show positive ΔS, while those consuming gases generally show negative ΔS.

Normal sentences must contextualise how calculations are performed in practice. Students should recognise that ΔS values help predict whether reactions tend towards greater or lesser molecular disorder.

Understanding Positive and Negative Entropy Changes

The sign and magnitude of ΔS help interpret the direction of energy dispersal within a system. Several qualitative trends guide expectations before quantitative analysis:

Factors that Increase ΔS

Increase in the number of gaseous molecules

Formation of more complex or flexible molecular structures

Dissolution of ionic solids into aqueous ions

Phase changes towards more disordered states

Factors that Decrease ΔS

Reduction in gaseous molecule count

Formation of ordered solid structures

Precipitation of ions into a crystalline lattice

Phase changes towards more ordered states

These patterns align with molecular freedom: greater freedom increases entropy, whereas constrained structures lower it.

Incorporating Related Quantities in Entropy Calculations

The syllabus requires students to “handle related quantities,” meaning reaction entropy may need to be combined or compared with additional thermodynamic data such as enthalpy changes or temperature conditions. Although full feasibility analysis arises later, the ability to work confidently with ΔS is foundational.

Total Entropy Change (ΔS_total): The combined entropy change of the system and surroundings during a reaction.

This broader quantity becomes essential when linking entropy to feasibility using free energy, but it also reinforces the conceptual difference between system changes (ΔS) and overall thermodynamic change.

Between definition blocks, it is useful to stress that data handling often involves careful unit checking, as entropy values always appear in J K⁻¹ mol⁻¹, while enthalpy values appear in kJ mol⁻¹.

Systematic Approach to Reaction Entropy Calculations

A consistent methodology ensures accuracy and avoids common errors in entropy work:

Step-by-Step Structure

Identify all reactants and products, ensuring the chemical equation is fully balanced.

Extract standard molar entropy values for each species from supplied data tables.

Multiply each entropy value by its respective stoichiometric coefficient.

Sum all product entropy values.

Sum all reactant entropy values.

Apply the ΔS formula exactly as specified.

These steps reflect the direct link between reaction stoichiometry and thermodynamic quantities.

Another important point is recognising how physical states influence entropy contributions. Always check state symbols, as solid, liquid, and gaseous forms have substantially different S° values.

Because S°(g) is usually much larger than S°(l) or S°(s), reactions that form gases (or increase gaseous moles) often give positive ΔS°, whereas reactions that reduce gaseous particles often give negative ΔS°.

This figure illustrates how entropy rises from solid to liquid to gas, reflecting greater particle freedom and explaining typical ΔS° trends in reactions. Source

Interpreting Entropy Calculations in Chemical Context

Entropy values alone do not determine whether a reaction will occur, but they provide essential insight into molecular-level changes. When ΔS is positive, reactions move towards greater disorder, often corresponding to gas evolution or dissolution. When ΔS is negative, the reaction favours more ordered structures.

Qualitative reasoning must accompany numerical work. For example, students should expect that reactions producing additional gaseous species will display positive ΔS, while those forming precipitates trend negative.

Reaction entropy, therefore, serves as both a calculable thermodynamic quantity and a conceptual indicator of changing disorder within a chemical system.

FAQ

Standard molar entropy values refer to substances measured at 298 K and 1 atm, with the substance in its standard physical state.

These conditions ensure consistency across data tables so that entropy comparisons and ΔS calculations remain valid.

Entropy reflects the number of possible microstates available to particles. Even the most ordered solid has some vibrational motion above absolute zero.

Since microstates can never be fewer than one, entropy cannot be negative and is always reported as a positive quantity.

Stoichiometric coefficients determine how many moles of each species contribute to the overall entropy change.

Increasing coefficients for gaseous products, for example, greatly increases the weighted entropy contribution because gases have large S values.

Likewise, large coefficients for gaseous reactants can result in strongly negative ΔS values.

Dissolution breaks a solid lattice into freely moving ions, greatly increasing the number of accessible particle arrangements.

Positive ΔS is typically observed when one ordered structure produces multiple hydrated ions with significant freedom of motion.

Several observable features indicate the likely sign of ΔS:

An increase in the number of gas molecules usually gives positive ΔS.

Formation of solids from solutions or gases tends to produce negative ΔS.

Processes producing more mobile species (e.g., ions in solution) typically show increased disorder.

These expectations allow rapid predictions before consulting data tables.

Practice Questions

Standard molar entropy values for a reaction are:

Reactants: 215 J K⁻¹ mol⁻¹

Products: 260 J K⁻¹ mol⁻¹

Calculate the entropy change, stating its sign, and explain what this indicates about disorder.

(2 marks)

Marking points:

Calculates ΔS = +45 J K⁻¹ mol⁻¹ (260 − 215).

States that a positive value indicates an increase in disorder or greater energy dispersal.

(1 mark for correct numerical value, 1 mark for correct interpretation.)

A balanced reaction has the following standard molar entropy values (all in J K⁻¹ mol⁻¹):

2 A(g): 2 × 180

B(s): 45

Products: C(g) = 210, D(l) = 70, E(s) = 55

(a) Calculate the standard entropy change of the reaction.

(b) Explain, using the physical states and particle freedom, why the sign of your answer is expected.

(c) State one reason why entropy values must be multiplied by stoichiometric coefficients in calculations of ΔS.

(5 marks)

(a) Calculation of ΔS (3 marks):

Correctly sums reactants: (2 × 180) + 45 = 405.

Correctly sums products: 210 + 70 + 55 = 335.

Calculates ΔS = 335 − 405 = −70 J K⁻¹ mol⁻¹.

(One mark for each bullet above.)

(b) Explanation of sign (1 mark):

States that ΔS is negative because gaseous moles decrease overall, meaning reduced disorder or reduced particle freedom.

(c) Stoichiometric explanation (1 mark):

States that coefficients show the number of moles involved, and entropies must be scaled to reflect the correct amount of each substance.

(Only clear, correct statements gain marks.)