OCR Specification focus:

‘Recognise that negative ΔG does not guarantee feasibility due to kinetic factors.’

Kinetic limitations influence whether a reaction with a negative free energy change, ΔG, can actually proceed at a measurable rate. Even when thermodynamics predicts feasibility, slow reaction kinetics may prevent observable change.

Understanding the Gap Between Thermodynamics and Reality

A reaction predicted to be feasible thermodynamically is one with a negative Gibbs free energy change, ΔG. This condition indicates that products have lower free energy than reactants. However, feasibility in thermodynamic terms does not necessarily correspond to practical or observable reactivity. Many reactions remain extremely slow despite possessing a negative ΔG, and OCR requires students to recognise this distinction clearly.

The Role of Activation Energy

Reactions proceed only when particles collide with sufficient energy to overcome the activation energy barrier, the minimum energy required for reactants to form an activated complex. A negative ΔG indicates energetic favourability between reactants and products, but it does not provide information about the height of this barrier.

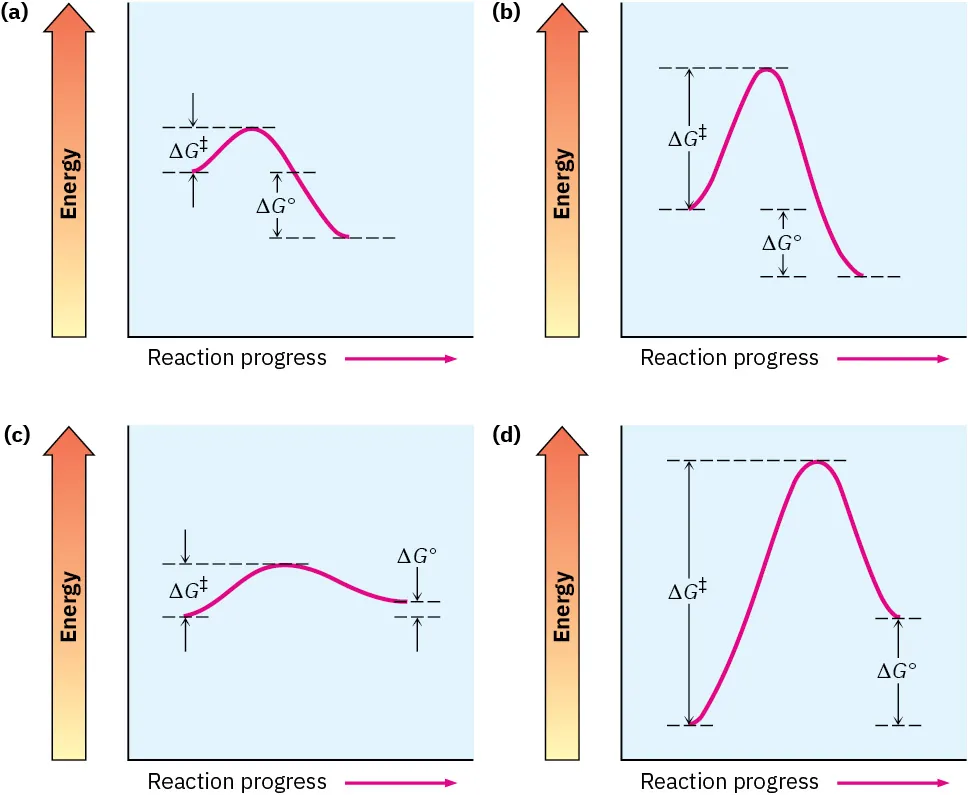

These diagrams illustrate that although ΔG may be negative, the reaction rate still depends on the height of the activation energy barrier, which controls the speed of reaction. Source

If the activation energy is very high, reactants may remain kinetically trapped.

Activation Energy: The minimum energy required for reacting particles to form the transition state and proceed to products.

Even highly exergonic reactions may be effectively ‘frozen’ if the activation energy is too large for collisions at the given temperature to overcome.

Free Energy and Its Limits in Predicting Feasibility

Thermodynamic feasibility is assessed using the Gibbs free energy relationship.

Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG) = ΔH − TΔS

ΔG = Free energy change, kJ mol⁻¹

ΔH = Enthalpy change, kJ mol⁻¹

T = Temperature, K

ΔS = Entropy change, kJ K⁻¹ mol⁻¹

A negative ΔG shows that the reaction is energetically favourable, but feasibility in the laboratory requires an adequate reaction rate. The Gibbs criterion alone does not include kinetic information, so students must appreciate that ΔG addresses direction, not speed.

A familiar example is the conversion of diamond into graphite. Although ΔG is negative, the process is imperceptibly slow under standard conditions because the activation energy is enormous.

Why Thermodynamically Feasible Reactions May Not Occur

Several kinetic factors can restrict the progress of reactions with negative free energy changes. These factors operate independently of thermodynamic favourability and relate to the molecular-scale behaviour of reacting species.

High Activation Energy Barriers

Most kinetic limitations stem from a high activation energy. When this barrier is large:

Collisions rarely have sufficient energy.

The transition state forms infrequently.

Molecules remain trapped in a metastable state despite favourable thermodynamics.

This creates a kinetically inert system, in which the reaction’s progress is too slow to detect.

Low Frequency of Effective Collisions

Even if activation energy is moderate, reactions may proceed slowly if reactants collide infrequently or with unfavourable orientations. Factors influencing collision success include:

Low reactant concentration

Restricted molecular motion (e.g., in solids)

Unfavourable steric orientations that reduce effective collisions

Structural and Mechanistic Constraints

Some reactions involve complex rearrangements or require simultaneous bond-making and bond-breaking processes. These additional structural constraints increase kinetic resistance. For example:

Multiple-step mechanisms with slow rate-determining steps

Strong, stable bonds requiring high input energy to initiate change

Transition states with significant geometric distortion

These mechanistic features slow reaction progress even when ΔG predicts that the products should be more stable.

Catalysts and Their Role in Overcoming Kinetic Barriers

Although negative ΔG may not guarantee observable reaction, catalysts can lower the activation energy and allow the reaction to proceed. Catalysts operate without altering ΔG because they do not affect the relative energies of reactants and products.

How Catalysts Change Reaction Feasibility in Practice

Catalysts can make a kinetically hindered but thermodynamically favourable reaction occur on a practical timescale by providing an alternative pathway with a lower activation energy.

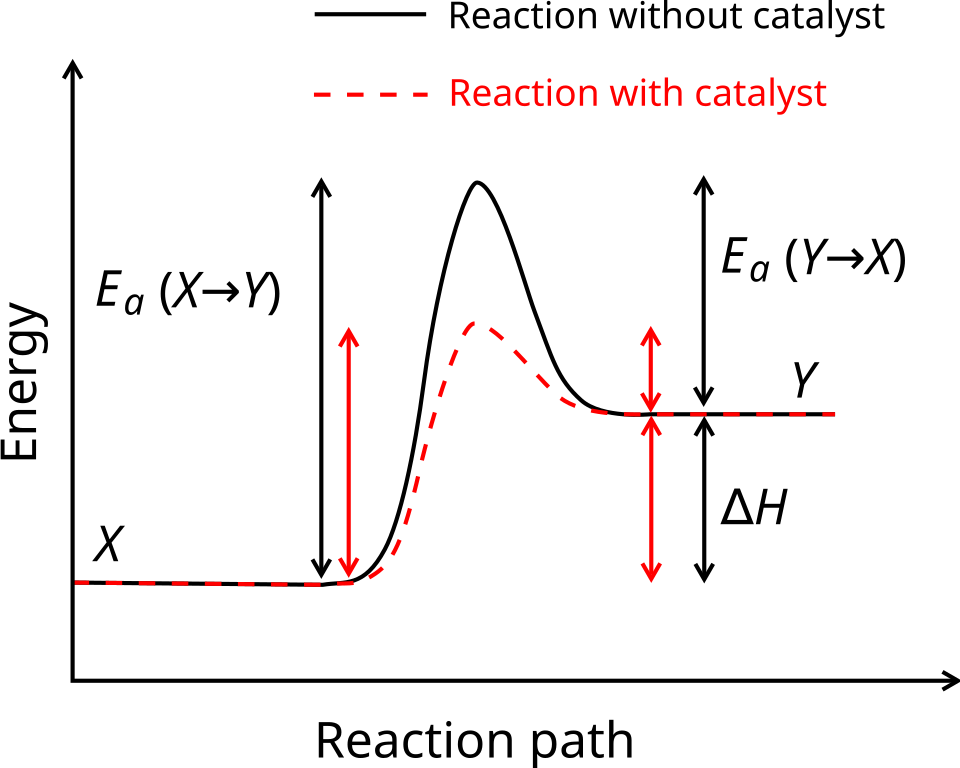

This diagram compares uncatalysed and catalysed reaction pathways, highlighting the reduced activation energy in the presence of a catalyst while the thermodynamic energy difference remains unchanged. Source

Catalysts improve reaction rates through several mechanisms:

Providing an alternative pathway with lower activation energy

Orienting reactants into more favourable configurations

Forming reactive intermediates that bypass slow steps

By increasing the proportion of collisions with sufficient energy, catalysts allow thermodynamically feasible processes to occur on a practical timescale. Catalysis therefore bridges the gap between theoretical feasibility and experimental observation.

Temperature and Its Influence on Kinetic Limitations

Temperature affects both thermodynamic and kinetic aspects of feasibility. In the Gibbs free energy equation, increasing temperature may make ΔG more negative if ΔS is positive. However, temperature also increases the kinetic energy of particles, enabling more collisions to exceed the activation energy barrier.

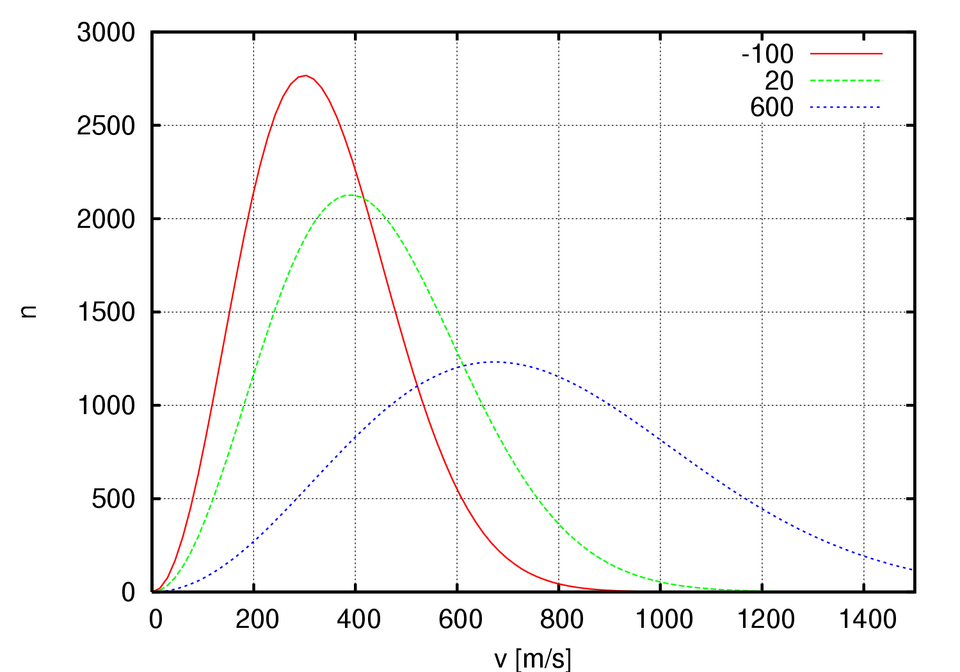

This Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution diagram shows how increasing temperature increases the fraction of particles with sufficient energy to overcome activation barriers, promoting faster reaction rates. Source

Kinetic Effects of Higher Temperature

Raising temperature generally:

Increases collision frequency

Increases collision energy

Enhances the fraction of molecules with energy above activation energy

Accelerates slow reactions that are otherwise effectively inert

Even so, for reactions with extremely high activation energies, reasonable laboratory temperatures remain insufficient to drive observable change.

Kinetic Control versus Thermodynamic Control

In some systems, reaction pathways compete. A kinetically controlled product forms fastest, whereas a thermodynamically controlled product has the lowest free energy. Students must recognise that:

Thermodynamics predicts the most stable product (negative ΔG).

Kinetics determines which product forms under specific conditions.

Low temperatures favour kinetic products; high temperatures favour thermodynamic products.

This distinction reinforces the idea that ΔG alone cannot dictate the outcome or rate of a chemical process.

FAQ

Kinetic limitations determine the rate at which a reaction approaches equilibrium, even when ΔG predicts the equilibrium position.

If the activation energy is very high, the reaction may take an extremely long time to reach equilibrium, making its position practically irrelevant on a laboratory timescale.

Slow kinetics can therefore cause a reaction mixture to appear unchanged, even though equilibrium strongly favours products.

A kinetic trap occurs when reactants are prevented from converting into more stable products because of a prohibitive activation energy barrier.

This means the system remains in a metastable state, despite a negative ΔG for the transformation.

Examples include solid-state rearrangements or reactions requiring major structural reorganisation.

Reactions that involve structural rigidity, strong covalent bonds, or extensive electron reorganisation often proceed extremely slowly.

Common examples include:

Rearrangement or phase-change processes in solids

Reactions with multiple slow mechanistic steps

Transformations involving very stable starting materials

Such systems highlight that feasibility based on ΔG does not guarantee observable reaction progress.

Changing conditions can reveal whether the barrier is kinetic rather than thermodynamic.

Useful checks include:

Raising temperature to see if rate increases

Adding a suitable catalyst

Monitoring reaction progress over an extended time period

If the reaction speeds up or eventually proceeds, this suggests kinetic, not thermodynamic, limitation.

Many natural processes involve complex molecular orientations, multi-step mechanisms, or very stable reactants.

Enzymes and environmental catalysts help overcome these kinetic barriers by lowering activation energy and aligning reactants correctly.

Without such catalysts, these reactions may occur over years or centuries, despite being thermodynamically favourable.

Practice Questions

Explain why a reaction with a negative Gibbs free energy change, ΔG, may not occur at a measurable rate under standard conditions.

(2 marks)

Award 1 mark for each of the following points:

A negative ΔG indicates thermodynamic feasibility only, not rate.

The reaction may have a high activation energy, preventing it from proceeding at a measurable rate.

A student states:

"Since ΔG is negative, the reaction must occur spontaneously and quickly."

Discuss why this statement is incorrect. In your answer, refer to:

kinetic limitations

activation energy

the effect of temperature

the role of catalysts.

(5 marks)

Award marks for any five valid points from the list below:

Negative ΔG shows that products are energetically more stable, but does not guarantee a fast reaction. (1 mark)

A reaction may be extremely slow if the activation energy barrier is large. (1 mark)

Few particles may have sufficient energy to overcome this barrier at the given temperature. (1 mark)

Increasing temperature increases the proportion of particles with enough energy to react, improving rate but not altering ΔG. (1 mark)

Catalysts lower the activation energy and increase reaction rate without changing ΔG. (1 mark)

Kinetics determines the speed of reaction, independent of thermodynamic favourability. (1 mark, maximum 5 marks total)